According to research from The University of Texas Health Science Center at Houston, debilitating cluster headaches commonly begin in childhood, but patients are not typically diagnosed until they are adults (UTHealth Houston).

The Cluster Headache Questionnaire, an international, internet-based survey of 1,604 cluster headache participants, was conducted by a team of researchers led by Mark Burish, MD, Ph.D., assistant professor in the Vivian L. Smith Department of Neurosurgery with McGovern Medical School at UTHealth Houston. The survey’s findings were recently published in Headache: The Journal of Head and Face Pain.

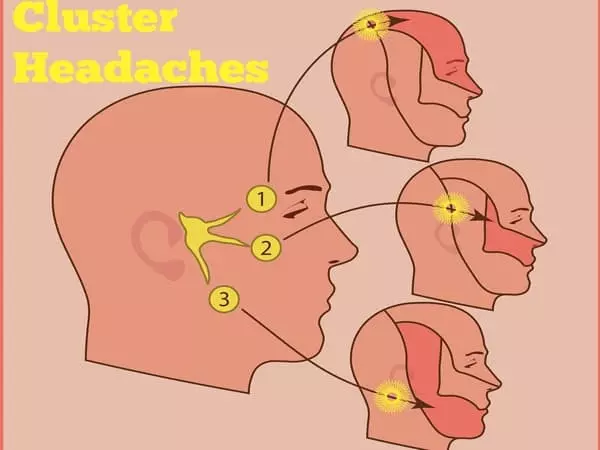

Cluster headache is a rare headache disorder that affects about one out of every 1,000 people. They are excruciatingly painful and occur in cyclical patterns known as cluster periods, with the majority of attacks occurring at the same time each day. Cluster headache is classified as “episodic” when attacks last between seven days and a year and are separated by pain-free periods of three months or longer. Meanwhile, in “chronic” cluster headaches, attacks last more than a year without remission or last less than three months.

Our research shows that it frequently begins in childhood, and that many children go years without a correct diagnosis, presumably suffering the entire time because they don’t have access to the appropriate treatments. I hope that this study will change the perception that cluster headaches only affect adult men.

Mark Burish

The headaches are similar to migraines, but there are some important distinctions. Cluster headaches, as opposed to migraines, which can last an entire day or even several days if left untreated, typically last 15 to 180 minutes. While having more than one migraine per day is unusual, it is possible to have up to eight cluster headaches in a 24-hour period. Furthermore, migraine pain can vary in location; in contrast, cluster headaches affect only one side of the head, usually at the temple or around the eye. Finally, people with migraines prefer to rest in a quiet, dark room, whereas people with cluster headaches become restless and frequently pace around the room.

There is very little information available on several aspects of cluster headache, including pediatric-onset cluster headache and the comparative effectiveness of cluster headache treatments.

“I hope that this study will change the perception that cluster headaches only affect adult men,” said Burish, who is also affiliated with The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center UTHealth Graduate School of Biomedical Sciences. “Our research shows that it frequently begins in childhood, and that many children go years without a correct diagnosis, presumably suffering the entire time because they don’t have access to the appropriate treatments.”

Significantly, 27.5 percent of survey participants had pediatric onset, but only 15.2 percent of those with pediatric onset were diagnosed before the age of 18.

While the reasons for this trend are unknown, Burish has developed several hypotheses based on discussions with pediatric neurologists, patients, and their parents. Because it is uncommon, family members and doctors are failing to recognize it, and patients are not being referred to the appropriate specialists. Also, because there are minor differences between children and adults in other headaches such as migraine, features of cluster headache in children may differ from those in adults.

According to Burish, the study also revealed that women with cluster headaches have higher pain intensity, nausea, and depression scores than men.

Other key survey findings include:

(1) While previous research has shown that women are more likely to suffer from migraines between the ages of 10 and 50, the opposite is true for cluster headaches: men were more likely to suffer from episodic cluster headaches between the ages of 10 and 50. For the other ages, the sex ratio was roughly equal.

(2) The overwhelming majority of respondents (99.0 percent) had at least one symptom involving an autonomic nervous system reaction, such as red eye or nasal congestion, and had restlessness (96.6 percent), but many also had prototypical migraine features, such as sensitivity to light and sound (50.1 percent), pain aggravated by physical activity (31.4 percent), or nausea and vomiting (27.5 percent).

(3) Interestingly, when compared to episodic cluster headache, the first-line medications for acute treatment (oxygen) and preventive treatment (calcium channel blockers) were perceived as significantly less effective in chronic cluster headache.

Burish stated that the study unearthed some smaller tidbits of information worthy of future research in addition to this epidemiological data.

“Cluster headache appears to begin at a younger age in patients with a family history of cluster headache than in patients without a family history,” Burish said. “In genetics, this is known as ‘anticipation,’ and it suggests that a gene or genes may be involved. Identifying those genes could be a huge step forward in the treatment of cluster headache.”