Individualized computing has gotten more modest and more personal throughout the long term — from the work station to the PC, to cell phones and tablets, to brilliant watches and savvy glasses.

In any case, the up and coming age of wearable figuring innovation — for wellbeing and health, social communication and horde different applications — will be considerably nearer to the wearer than a watch or glasses: It will be joined to the skin.

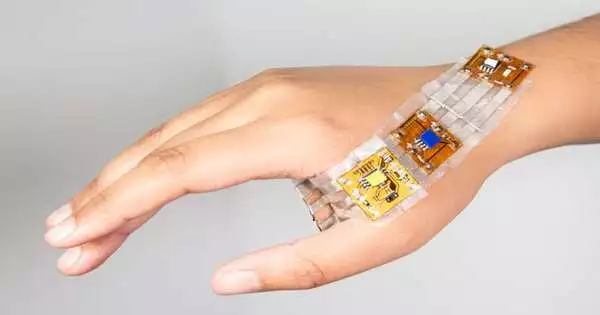

On-skin interfaces — in some cases known as “shrewd tattoos” — can possibly beat the detecting capacities of current wearable advancements, however joining solace and sturdiness has demonstrated testing. Presently, individuals from Cornell’s Mixture Body Lab have thought of a solid, skin-tight point of interaction that is not difficult to connect and withdraw, and can be utilized for various purposes — from wellbeing observing to mold.

“We’ve been working on this for years, and I believe we’ve finally solved a lot of the technological hurdles; we wanted to establish a modular approach to smart tattoos, to make them as simple to build as Legos.”

Cindy (Hsin-Liu) Kao, assistant professor of human centered design in the College of Human Ecology,

Doctoral understudy and lab part Pin-Sung Ku is lead creator of “SkinKit: Development Unit for On-Skin Connection point Prototyping,” which was introduced in September at UbiComp ’22, the Relationship for Processing Apparatus’ global joint gathering on unavoidable and pervasive figuring.

“We’ve been dealing with this for quite a long time, and I think we’ve at last sorted out a ton of the specialized difficulties,” said Cindy (Hsin-Liu) Kao, right hand teacher of human focused plan in the School of Human Biology, and the review’s senior creator. “We needed to make a measured way to deal with shrewd tattoos, to make them as direct as building Legos.”

SkinKit — a fitting and-play framework that intends to “bring down the floor for section” to on-skin interfaces, Kao said, for those with practically no specialized skill — is the result of endless long periods of improvement, testing and redevelopment, she said.

Kao’s lab is additionally exceptionally aware of social contrasts for the most part, and she believes carrying these gadgets to different populations is significant.

“Individuals from various societies, foundations and nationalities can have altogether different discernments toward these gadgets,” she said. “We felt it’s quite critical to give more individuals have a voice access getting out whatever they maintain that these savvy tattoos should do.”

The SkinKit wearable detecting connection point, created in the Mixture Body Lab, can be utilized for wellbeing and health, individual security, as assistive innovation and for athletic preparation, among numerous applications. Credit: Cross breed Body Lab/Gave

Manufacture is finished with brief tattoo paper, silicone material stabilizer and water, making a multi-facet meager film structure the gathering calls “skin fabric.” The layered material can be cut into wanted shapes — for their review, the specialists utilized three-quarter-inch squares, with male-female cutting lines so the pieces can be decorated (combined) — and fitted with scaled down adaptable printed circuit board modules to play out a scope of errands.

“The beginning stage was to find a reasonable structure variable, and afterward to make it versatile,” Ku said. “What’s more, the manner in which we scale it is through the decoration design. So then, at that point, the client can plan a circuit and afterward tweak the design by assembling numerous modules.”

One of the advantages of their plan, Ku said, is the reusability part.

“The wearer can undoubtedly connect them together and furthermore withdraw them,” he said. “Suppose that today you need to involve one of the sensors for specific purposes, yet tomorrow you need it for something else. You can without much of a stretch simply confine them and reuse a portion of the modules to make another gadget in minutes.”

To test SkinKit, the specialists previously selected nine members with both STEM and configuration foundations to construct and wear the gadgets. Their contribution from the hour and a half studio informed further changes, which the gathering performed prior to directing a bigger, two-day study including 25 members with both STEM and configuration foundations.

Gadgets planned by the 25 review members tended to: wellbeing and health, including temperature sensors to recognize fever because of Coronavirus; individual security, including a gadget that would assist the wearer with keeping social separation during the pandemic; warning, including an arm-worn gadget that a sprinter could wear that would vibrate when a vehicle was close; and assistive innovation, for example, a wrist-worn sensor for the visually impaired that would vibrate when the wearer was going to catch an item.

Different applications were for social, style and athletic preparation purposes.

Kao expressed individuals from her lab, including Ku, participated in the 4-H Profession Investigations Gathering over the late spring, and had around 10 center schoolers from upstate New York construct their own SkinKit gadgets.

“I think it simply shows us a great deal of potential for STEM learning, and particularly to have the option to draw in individuals who perhaps initially wouldn’t have interest in STEM,” Kao said. “In any case, by joining it with body workmanship and style, I believe there’s a great deal of potential for it to draw in the future and more extensive populaces to investigate the eventual fate of shrewd tattoos.”

More information: Pin-Sung Ku et al, SkinKit, Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies (2021). DOI: 10.1145/3494989