According to a new University of Michigan-led study, the first direct evidence that adult males experienced musth, a testosterone-driven episode of heightened aggression against rival males, is provided by traces of sex hormones extracted from a woolly mammoth’s tusk.

Blood and urine tests had previously shown that male elephants’ musth consumption was associated with elevated testosterone levels. Skeletal injuries, broken tusk tips, and other indirect evidence have been used to infer musth battles in modern-day relatives of elephants.

Yet, the new review, booked for online distribution May 3 in the journal Nature, is quick to show that testosterone levels are kept in the development layers of mammoth and elephant tusks.

The U-M scientists and their global partners report every year repeating testosterone floods — up to multiple times higher than standard levels — inside a permafrost-saved wooly mammoth tusk from Siberia. Over 33,000 years ago, the adult male mammoth lived.

“This discovery establishes dentin as a useful hormone repository and paves the way for further developments in the emerging field of paleoendocrinology, Tooth-hormone records could support medical, forensic, and archaeological studies, in addition to broad applications in zoology and paleontology.”

Lead author Michael Cherney, a research affiliate at the U-M Museum of Paleontology.

According to the authors of the study, the musth-related testosterone peaks that the researchers observed in an African bull elephant tusk are consistent with the testosterone surges that were observed in the mammoth tusk. The Hindi and Urdu words for drunkenness are the source of the word “mush.”

Michael Cherney, lead author of the study and a research fellow at the University of Michigan Medical School, stated, “Temporal patterns of testosterone preserved in fossil tusks show that, like modern elephants, mature bull mammoths experienced musth.” Cherney is a research affiliate at the University of Michigan Museum of Paleontology.

The study demonstrates that testosterone and other steroid hormones can be found in ancient and modern tusks. Dentin, the mineralized tissue that covers the inside of all teeth (tusks are elongated upper incisor teeth), contains these chemical compounds.

“This study lays out dentin as a helpful storehouse for certain chemicals and makes way for additional advances in the emerging area of paleoendocrinology,” Cherney said. “Tooth-hormone records could assist in medical, forensic, and archaeological research, in addition to their wide range of applications in paleontology and zoology.”

Chemicals are flagging particles that assist with directing physiology and conduct. The main sex hormone in male vertebrates is testosterone, which belongs to the steroid hormone family. It moves through the blood and builds up in various tissues.

Steroid hormones found in human and animal hair, nails, bones, and teeth have previously been studied by scientists in both modern and ancient contexts. Yet the importance and worth of such chemical records have been the subject of continuous investigation and discussion.

The creators of the new Nature concentrate on saying their discoveries ought to assist with changing that by exhibiting that steroid records in teeth can give significant organic data that occasionally endures for millennia.

According to study co-author Daniel Fisher, a professor in the Department of Earth and Environmental Sciences and curator at the U-M Museum of Paleontology, “tusks hold particular promise for reconstructing aspects of mammoth life history because they preserve a record of growth in layers of dentin that form throughout an individual’s life.”

Fisher, who is also a professor in the U-M Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, stated, “Because musth is associated with dramatically elevated testosterone in modern elephants, it provides a starting point for assessing the feasibility of using hormones preserved in tusk growth records to investigate temporal changes in endocrine physiology.”

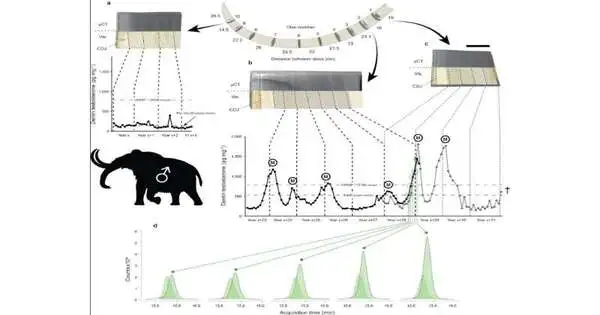

The researchers took samples of the tusks of one adult African bull elephant and two adult Siberian woolly mammoths, one male and one female. The examples were acquired as per applicable regulations and with fitting grants.

The scientists utilized CT sweeps to recognize yearly development increases inside the tusks. Under a microscope, a tiny drill bit was used to grind contiguous half-millimeter-wide samples representing approximately monthly dentin growth across a block of dentin using computer-controlled stepper motors.

The powder created during this processing system was gathered and synthetically investigated.

To extract steroids from tusk dentin for measurement with a mass spectrometer, an instrument that sorts ions according to their mass and charge, new methods had to be developed in the laboratory of U-M endocrinologist and study co-author Rich Auchus.

“We had developed steroid mass spectrometry methods that we used extensively in clinical research studies for samples of human blood and saliva.” However, Auchus, a professor of internal medicine and pharmacology at the University of Michigan Medical School, stated, “Never in a million years did I imagine that we would be using these techniques to explore “paleoendocrinology.” “

“We needed to alter the strategy some, since those tusk powders were the dirtiest examples we at any point broke down. At the point when Mike (Cherney) showed me the information from the elephant tusks, I was confounded. Then we saw similar examples in the mammoth — goodness!”

When a hunter killed the African bull elephant in Botswana in 1963, it was probably between 30 and 40 years old. The male woolly mammoth lived to about 55 years old, according to estimates based on growth layers in its tusk. In 2007, a diamond-mining company found its right tusk in Siberia. According to radiocarbon dating, the animal existed between 33,291 and 38,866 years ago.

Woolly mammoth tusks in the early morning light on Wrangel Island, in the northeast of Siberia This is where the female mammoth tusk that was used in the testosterone study was found several years before. The day before the picture was taken, these tusks were collected, and they were put together for measurement and preliminary sampling. Credit: Daniel Fisher, Michigan University

Wrangel Island, which was connected to northeast Siberia during glacial periods of lower sea level but is now separated from it by the Arctic Ocean, was the location where the female woolly mammoth’s tusk was discovered. The age determined by carbon dating was between 5,597 and 5,885 years ago. The last known location where woolly mammoths lived was Wrangel Island, around 4,000 years ago.

The average testosterone level in the female woolly mammoth tusk was lower than the lowest values recorded in the male mammoth’s tusk records, in contrast to the male tusks’ little variation over time.

“These methods could be used to investigate records of organisms with smaller teeth, including humans and other hominids, with reliable results for some steroids from samples as small as 5 mg of dentin,” the authors wrote. A novel method for studying reproductive ecology, life history, population dynamics, disease, and behavior in modern and prehistoric contexts is provided by endocrine records in modern and ancient dentin.”

More information: Michael Cherney, Testosterone histories from tusks reveal woolly mammoth musth episodes, Nature (2023). DOI: 10.1038/s41586-023-06020-9. www.nature.com/articles/s41586-023-06020-9