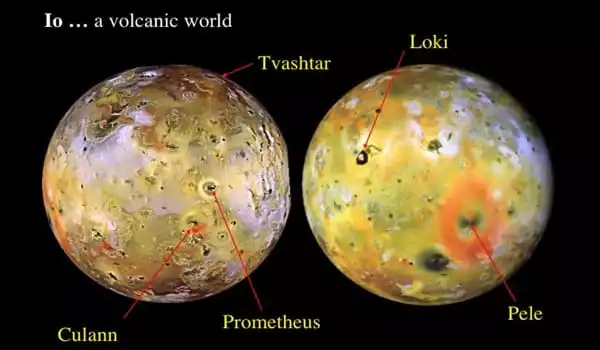

The Io Volcano Observer (IVO) mission would travel to Jupiter’s moon Io, which is a veritable volcanic paradise with hundreds of erupting volcanoes spewing tons of molten lava and sulfurous fumes at any given time.

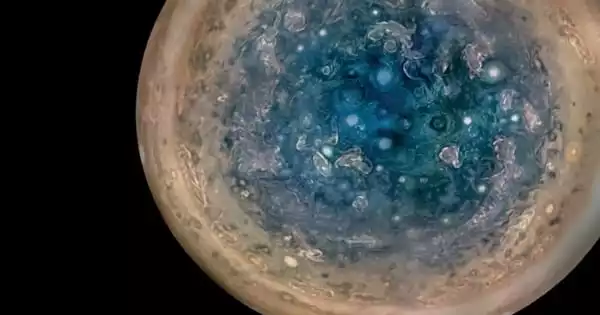

This may have been the surface of any nascent rocky planet a few billion years ago. However, in our solar system now, only Io exhibits this level of excitement. Io is subjected to harsh tides as it swings along its elliptical course due to the massive pull of Jupiter’s gravity and the passing orbital tugs of sister moons Europa and Ganymede.

That finding, described in Nature Communications, suggests that dunes may be more common on other worlds than previously thought, though the lumps may form in odd ways.

“In some ways, these [other worlds] are starting to look more familiar,” says George McDonald, a planetary scientist at Rutgers University in Piscataway, New Jersey. “But the more you think about it, the more exotic they seem.”

Io is a world filled with erupting volcanoes caused by Jupiter’s and some of its other moons’ gravitational forces pulling on Io and generating heat. Hummocky ridges were discovered on Io’s dynamic surface over 20 years ago by scientists. The features mimic dunes, but that couldn’t be since Io’s atmosphere is too thin for winds to whip up a dunescape, scientists reasoned.

I believe a lot of scientists looked at those and thought, oh, these may truly be dunes. What’s amazing is that they’ve devised a good physical mechanism to explain how it’s possible.

Jani Radebaugh

However, dunelike features have recently been observed on comet 67P and Pluto, both of which lack extensive atmospheres. McDonald and his colleagues returned to the subject of Io’s strange lumps, inspired by those extraterrestrial dunescapes. All they needed was an aerial force to shape the moon’s dunes.

When molten rock flows collide with bodies of water on Earth, huge explosions of steam occur. While there is no water on Io, sulfur dioxide frost is common. As a result, the scientists believe that as lava slowly flows into and just beneath a frost layer, jets of sulfur dioxide gas may emerge from the frost. These jets could propel fragments of rock and other debris into the air, generating dunes.

According to the researchers, an expanding lava flow buried beneath at least 10 cm of frost might sublimate some of the frost into pockets of hot vapor. When enough vapor builds and the pressure rises to match or exceed the weight of the overlying frost, the vapor can explode out at speeds of up to 70 kilometers per hour. According to the researchers, these bursts might propel grains with diameters ranging from 20 micrometers to one centimeter.

Tidal heating could be distributed throughout the moon’s interior or concentrated closer to its surface, depending on the distribution of solid and molten rock. So IVO would detect the gravity and magnetic fields surrounding Io to determine what’s going on inside.

One intriguing theory is that Io possesses a worldwide magma ocean beneath its relatively cold, stony surface. As Jupiter’s magnetic field sweeps across the moon, IVO would detect the distortion in the magnetic field caused by currents created inside the electrically conductive magma, yielding a different reading than if Io’s interiors were mostly solid.

Images of Io’s surface acquired by NASA’s now-defunct Galileo mission revealed highly reflective streaks of material radiating outward over dunes in advance of lava flows — likely material newly deposited at the time by vapor jets.

Furthermore, using the photos to assess the hummocky characteristics revealed that their size match those of dunes on other planets. The crew thinks that some of the Ionian dunes are over 30 meters high.

IVO would also use geophysical measurements and new topographic maps to better understand the thickness and movement of Io’s cold, rocky outer layer, as well as provide insights into how the Earth, Moon, and other rocky planets functioned shortly after their formation, when they were cooling magma-ocean worlds.

“I believe a lot of [scientists] looked at those and thought, oh, these may truly be dunes,” Jani Radebaugh, a planetary scientist at Brigham Young University in Provo, Utah, who was not involved in the study, says. “What’s amazing is that they’ve devised a good physical mechanism to explain how it’s possible.”

Io is commonly conceived of as a volcanic world. According to McDonald, the presence of dunes shows that there is more going on there than scientists previously imagined. “It certainly adds another element of complication.”