There’s an abnormal, bothersome issue with how we might interpret nature’s regulations, which physicists have been attempting to make sense of for quite a long time. It’s about electromagnetism, the law of how particles and light collaborate, which makes sense of everything from why you don’t fall through the floor to why the sky is blue.

Our hypothesis of electromagnetism is apparently the best actual hypothesis people have made, yet it has no solution for why electromagnetism is a major area of strength, however that seems to be. Only tests can see electromagnetism’s solidarity, which is measured by a number known as (also known as alpha, or the fine-structure steady).

The American physicist Richard Feynman, who helped concoct the hypothesis, referred to this as “one of the best damn secrets of material science” and encouraged physicists to “set this number up on their wall and stress over it.”

In a recent study published in Science, we decided to test whether is the best place in our universe by focusing on stars that are nearly identical twins of our sun.If it differs in better places, it may help us track down a definitive hypothesis of electromagnetism, however, of all of nature’s laws put together—the “hypothesis of everything.”

We need to break our number one hypothesis.

Physicists truly need a certain something: a circumstance where our ongoing comprehension of material science separates. new physical science a sign that can’t be made sense of by current speculations. A signpost for the hypothesis of everything

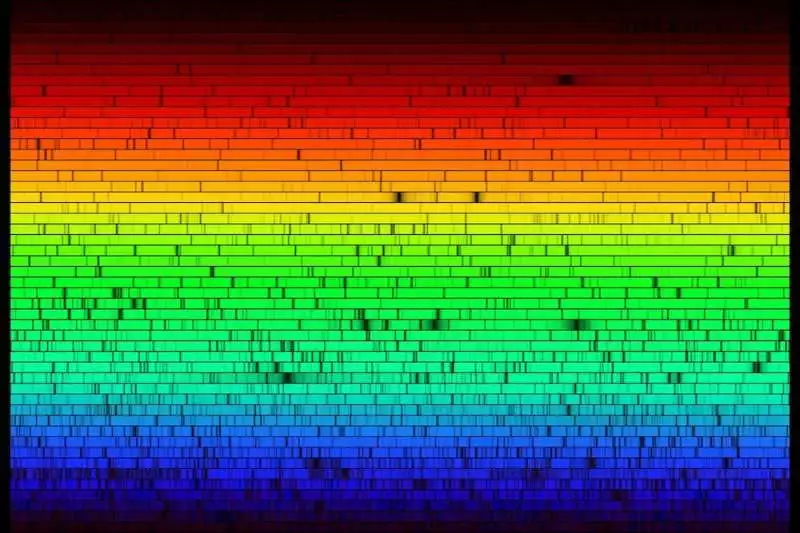

The sun’s rainbow: daylight is here spread into discrete columns, each covering simply a little scope of varieties, to uncover the numerous dim retention lines from particles in the sun’s climate.

To find it, they could dig deeply underground in a mother lode for particles of dim metal that make a difference and crash into an extraordinary gem. Or, on the other hand, they could cautiously tend the world’s best nuclear clocks for quite a long time to check whether they tell marginally unique time. Or, on the other hand, crush protons together at (almost) the speed of light in the 27-km ring of the enormous Hadron Collider.

The difficulty is that it’s difficult to tell where to look. Our ongoing speculations can’t direct us.

Obviously, we search in research facilities around the world, where it is easiest to look completely and precisely.Yet, that is a bit like the alcoholic just looking for his lost keys under a light post when, really, he could have lost them on the opposite roadside, someplace in a dim corner.

The stars are horrible, but occasionally horrifyingly comparable.

We chose to look past Earth, past our nearby planet group, to check whether stars that are almost indistinguishable twins of our sun produce a similar rainbow of varieties. Iotas in the environments of stars retain a portion of the light battling outwards from the atomic heaters in their centers.

Only certain tones are retained, leaving dull lines in the rainbow. Those who have been assimilated are still in the air, so estimating the dull lines cautiously also allows us to gauge.

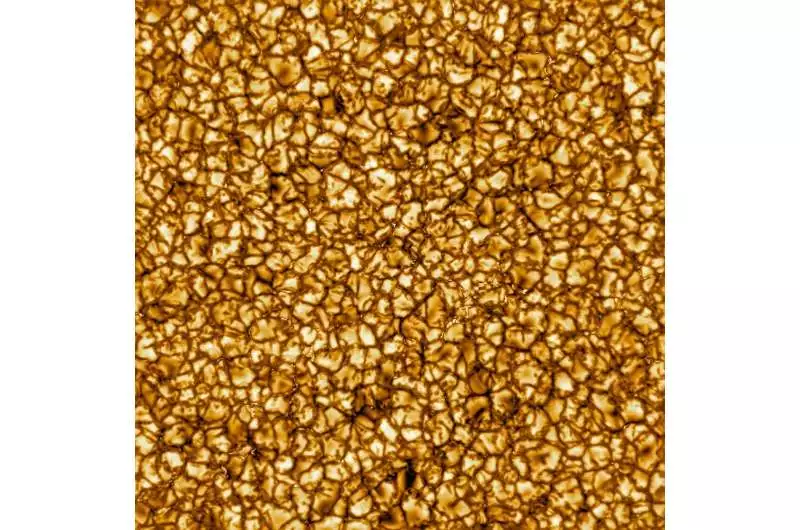

More sweltering and cooler gas rising through the fierce climates of stars make it hard to contrast assimilation lines in stars with those found in research center trials.

The issue is that the environments of the stars are moving—bbubbling, turning, circling, burping—aand this moves the lines. The movements demolish any investigation along similar lines in research facilities around the world, and thus any possibility of estimating.Stars, it appears, are awful places to test electromagnetism.

Yet, we pondered: in the event that you find stars that are practically the same—ttwins of one another—pperhaps their dull, retained colors are comparative too. So rather than contrasting stars with labs on the planet, we contrasted the twins of our sun with one another.

Another test with sun-based twins

Our group of undergrads, postdocs, and senior specialists at Swinburne College of Innovation and the College of New South Grains estimated the separation between sets of retention lines in our sun and 16 “sun oriented twins”—stars practically undefined from our sun.

The rainbows from these stars were seen on the 3.6-meter European Southern Observatory (ESO) telescope in Chile. While not the biggest telescope on the planet, the light it gathers is taken care of by presumably the best-controlled and best-grasped spectrograph: HARPS. This separates the light into its tones, revealing a detailed example of dull lines.

HARPS invests quite a bit of its energy in noticing sun-like stars to look for planets. Conveniently, this gave a mother lode of the very information we wanted.

The ESO 3.6-meter telescope in Chile invests quite a bit of its energy in noticing sun-like stars to look for planets, utilizing its very precise spectrograph, HARPS.

We demonstrated that was similar in the 17 sun-powered twins with startling precision: only 50 sections for every billion. This is analogous to contrasting your level with the Earth’s circuit. It is the most precise galactic trial ever performed.

Tragically, our new estimations didn’t break our number-one hypothesis. In any case, the stars we’ve contemplated are generally close by, up to 160 light years away.

What’s straightaway?

As of late, we’ve recognized new sunlight-based twins a lot further away, most of the way to the focal point of our Smooth Way world.

Around here, there ought to be a lot higher centralization of dull matter, a subtle substance that stargazers accept sneaking all through the world and then some. For example, we have little understanding of dim matter, and a few hypothetical physicists suggest that the internal pieces of our world may be only the dull corner in which we should look for associations between these two “damn secrets of material science.”

On the off chance that we can notice these considerably farther-off stars with the biggest optical telescopes, perhaps we’ll track down the keys to the universe.

More information: Michael T. Murphy et al, A limit on variations in the fine-structure constant from spectra of nearby Sun-like stars, Science (2022). DOI: 10.1126/science.abi9232

Journal information: Science