Imagine the view from the west coast of South Africa during the Last Ice Age (LGM) 20,000 years ago. hundreds of millions. Habitat for seabirds and penguins.

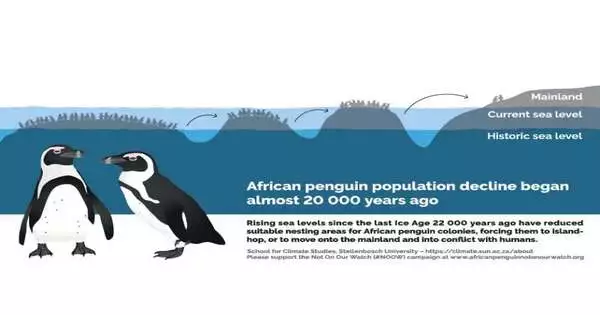

Imagine now that between 15,000 and 7,000 years ago, the sea level rose by 100 meters, gradually covering these large islands and leaving only small hills and hills above the water. Over the past 22,000 years, this habitat has increased ten times the amount of habitat suitable for African penguins, causing their populations to decline.

This is a palaeohistoric snapshot of the African penguin’s geographic range, created by scientists from the Department of Botany and Zoology and the Evolutionary Genomics Research Group at Stellenbosch University’s (SU) School of Climate Research. Through these efforts, they hope to shed new light on the current vulnerability of Africa’s last remaining penguin species.

“Penguin populations may have been significantly impacted by this. Climate change, habitat damage, and food competition are now added human stresses that these populations must contend with.”

Dr. Heath Beckett, first author of the article.

On April 20, 2023, a study titled “Terminal Pleistocene natural decline in African penguin populations increases risk of anthropogenic extinction” was published in the African Journal of Marine Science. Dr. Heath Beckett, first author of the paper and a postdoctoral fellow at SU’s School of Climatic Research, says this million-dollar picture of paleo-death contrasts sharply with the current reality of African penguin population declines since 1900.

In 1910, Dasen Island (an island off the west coast with an area of about 3 square kilometers) was home to about 1.45 million penguins. However, by 2011, the total population of African penguins in South Africa had declined to 21,000 pairs, and by 2019, it was down to 13,600 pairs. About 97% of South Africa’s current penguin population is supported by seven breeding colonies. In May 2005, the International Union for Conservation of Nature classified African penguins as endangered.

Archaeological estimates of penguin population sizes

What were the south and west coasts of South Africa like during the last ice age? What can this tell us about the size of the penguin population?

Because penguins like to breed on islands to escape mainland predators, the researchers used underwater topographic maps of the South African coast to identify historical islands that were 10 to 130 meters below current sea level. To be suitable for penguins to live on, the island had to be surrounded by areas suitable for feeding sardines and anchovies within a radius of 20 km to provide protection from predators on land.

Assuming sea levels were much lower during the last ice age, the researchers identified 15 large islands off the west coast, the largest of which is 300 square kilometers, 130 meters below sea level. Then, taking into account sea level rise over the past 15,000 to 7,000 years, they identified 220 islands that provide suitable nesting conditions for penguins. The 216 islands are less than one square kilometer in size, and some are only 30 square meters, missing a rock. Today, the five largest islands off the west coast of South Africa are Robben Island (5 km2), Dassen Island (3 km2), Possession Island (1.8 km2), Seal Island, and Penguin Island (both with less than 1 km2). Possession, Seal, and Penguin Islands are all off the coast of Namibia. The researchers calculated penguin population estimates based on the available island area based on the earliest possible estimates of population density, assuming that penguins typically nest within 500 m of shore.

Using this approach, they estimate that between 6.4 million and 18.8 million people would have occupied Southern Cape waters during the Last Glacial Maximum. However, rising sea levels between 15 and 7,000 years ago severely damaged the nesting habitats of African penguins.

According to Dr., the main purpose of the station is to show that there have been significant changes in habitat availability over the past 22,000 years. “It may have had a major impact on penguin populations, which are now facing additional human pressures in the form of climate change, habitat destruction, and competition for food,” he explains.

Implications for Wildlife management

While this discovery is a serious concern, the researchers say it demonstrates the African penguin’s potential as a resilience reserve that can be used to conserve and manage an uncertain future.

Dr. Beckett explains: “This historical flexibility of response gives conservation managers the freedom to use suitable breeding grounds on terrestrial sites until suitable breeding grounds become available.”

According to co-author Professor Guy Midgley and Acting Director of SU’s School of Climate Research, this series of millennial-scale selection pressures may have contributed to the species’ robust colonization capacity. “I’m a total survivor, and if given half a chance, I’d stick with it. I’ve done the island before, and I know how,” he said. But even if we could move, how long would it last under the increasing pressures of modern man? In the battle for commercial fishing and the same food source for all of humanity, penguins and other sea creatures may not stand a chance. So if “relocation measures are to be successful,” the researchers warn, “adequate access to marine food resources remains an integral part of concerted efforts to prevent species extinction.”

More information: A natural terminal Pleistocene decline of African penguin populations enhances their anthropogenic extinction risk, African Journal of Marine Science (2023). DOI: 10.2989/1814232X.2023.2171126