According to new Cornell-led research, humidity is just as important as scent in attracting pollinators to a plant. This advances fundamental biology and opens up new opportunities to support agriculture.

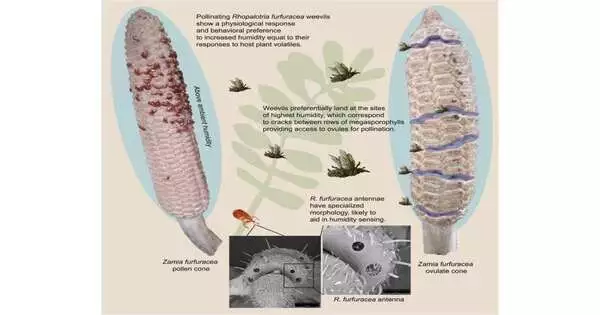

Researchers from Cornell, Harvard University, and the Montgomery Botanical Center conducted a study that was published in Current Biology. They discovered that the weevil that pollinates the plant Zamia furfuracea was just as sensitive to scent as it was to humidity.

“The universe of plant-bug connections was radically different by the work that was finished on visual and fragrance signals,” said first creator Shayla Salzman, a postdoctoral Public Science Establishment individual in the School of Integrative Plant Science Plant Science Segment, in the School of Horticulture and Life Sciences. ” Furthermore, presently we’re simply beginning to acknowledge the number of different elements that are assuming a part in plant generation and affecting bug navigation, fertilization and achievement.”

“The work on visual and odor cues has drastically changed the world of plant-insect interactions. And we’re only now seeing how many other elements influence plant reproduction and insect decision making, pollination, and success.”

Shayla Salzman, a postdoctoral National Science Foundation.

Robert Raguso, professor of neurobiology and behavior (CALS), is one of the co-authors. The Barbara McClintock Professor of Plant Biology (CALS), Chelsea Specht; Raguso’s Ph.D. candidate, Ajinkya Dahake; what’s more, Will Kandalaft ’21.

Dahake was first creator of a notable report distributed in 2022 in Nature Correspondences that found mugginess was going about as a sign to urge hawkmoths to fertilize the sacrosanct datura bloom (Datura wrightii). Dahake said that when taken as a whole, the studies show that two very different plants actively use humidity to encourage pollination.

He stated, “Before our research, humidity was thought to be just a side effect of nectar evaporation.” We have discovered that this is an active process that occurs within the flower and is carried out by specialized cells. These organisms may even have evolved to prioritize the release of humidity because it attracts pollinators.

As of not long ago, the investigation of fertilization and plant-bug collaborations has zeroed in on clear line of sight and aroma markers — faculties that people can likewise decipher. Salzman stated that insects, on the other hand, are much better than humans at detecting changes in temperature, carbon dioxide, and humidity.

She stated, “It’s crucial that we understand how insects utilize all of that information in their interactions with plants, especially as climate change directly impacts exactly those things.”

According to Salzman, such information could be used by farmers and food distributors, for instance, to encourage pollination of food crops or to direct insects away from stored foods and toward traps.

According to Dahake, insects can detect minuscule changes in humidity, whereas humans require relatively large changes in humidity to detect them.

“Bugs have specific receptors that answer tiny changes in stickiness: “A neuron will fire even if there is a change of 0.2 to 0.3 percent,” he stated. An insect neuron will respond to a change in carbon dioxide concentration of even one part per million. What does that mean in terms of behavior? We are only scratching the surface here.

More information: Shayla Salzman et al, Cone humidity is a strong attractant in an obligate cycad pollination system, Current Biology (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.cub.2023.03.021