The experimental approach could lead to the discovery of new treatment options for the virus, which is prevalent in Western Africa. Scripps Research, in collaboration with the La Jolla Institute for Immunology, used a novel strategy to identify and study host cell proteins that contribute to Lassa virus multiplication, a virus that causes severe hemorrhagic fever disease. The discovery could lead to the identification of new drug targets for the treatment of the disease.

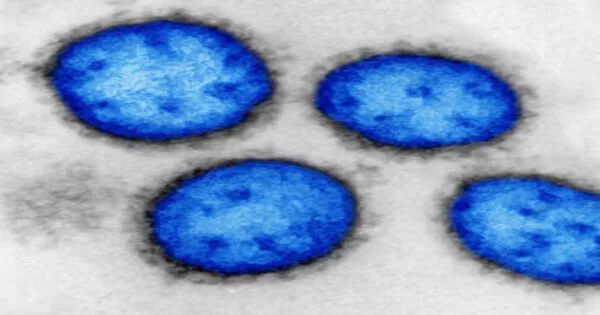

Lassa virus (LASV) is extremely common in Western Africa. The virus is typically transmitted to humans through contact with aerosols or infected rodent droppings and secretions. Infected people can develop Lassa fever (LF), a hemorrhagic fever disease with a high morbidity and mortality rate. Notably, many LF survivors suffer from long-term complications such as sensory-neural hearing loss. There are no licensed vaccines or treatments for LF, with the exception of off-label use of ribavirin, which has limited and controversial efficacy.

The research, led by Juan Carlos de la Torre, PhD, of Scripps Research, in collaboration with the laboratory of Erica Ollmann Saphire, PhD, at La Jolla Institute for Immunology, was published in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences (PNAS).

We think the experimental approach we used could be a rubric for any other highly pathogenic virus. You would have to change the components, but conceptually, the same approach could potentially be applied with any highly pathogenic virus requiring BSL4.

Juan Carlos de la Torre

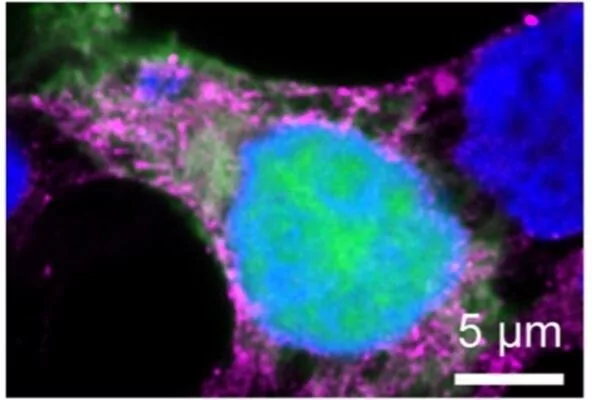

The researchers used a new strategy that combined proximity proteomics with the use of a non-infectious cell-based LASV minigenome system that recreates the molecular processes involved in LASV replication to identify host cell proteins that contribute to LASV replication. Proximity proteomics involves fusing a protein of interest to an enzyme that will label nearby proteins with a chemical tag, allowing them to be identified.

“Viruses don’t operate in isolation,” says Saphire. “They hijack and require molecules of the cell for their own purposes.”

De la Torre compares the process to how social networks “leave traces of interactions” and provide information about how people may be related to one another, such as whether two users live in the same city or household, or if they are family members or acquaintances.

“Just as with social media users, some interactions between proteins make sense, and you can infer relationships between the two,” he says. “Other protein interactions are casual or accidental and don’t mean anything, but, for many others, further investigation is required to uncover their biological implications.”

Using this combined approach, they were able to identify 42 cellular proteins that are likely to be involved in the replication and spread of LASV. One of the identified host proteins, GSPT1, may be a potential drug target, as CC-90009, a drug that specifically targets and degrades GSPT1, demonstrated antiviral activity against LASV without cytotoxicity. CC-90009 is currently in phase 1 clinical development for the treatment of acute myeloid leukemia, raising the prospect of its repurposing as an antiviral against LASV.

De la Torre notes that because this method of identifying viral-host cell protein interactions of interest can be done without the live, infectious LASV, this strategy does not require a biosafety level 4 (BSL4) lab, which are expensive to operate.

“We think the experimental approach we used could be a rubric for any other highly pathogenic virus,” he says. “You would have to change the components, but conceptually, the same approach could potentially be applied with any highly pathogenic virus requiring BSL4.”

Furthermore, according to de la Torre, identifying host cell proteins required for LASV replication can aid in the repurposing of drugs currently used for other indications as antivirals against LASV.

“This gives us an advantage,” he says, “because diseases like Ebola and Lassa are geographically limited, making it unlikely that pharmaceutical companies will develop drugs specifically for them.” Notably, Lassa and Ebola share a number of host cell proteins, which could aid in the development of broad-spectrum antivirals by targeting host factors used by both viruses.”

He points out that improved LASV treatment could have an impact outside of Western Africa, as increased travel to and from LASV endemic areas has resulted in the importation of LF cases into metropolitan areas outside of Western Africa.

“People doing humanitarian work in Western Africa, whether clinical or social work, can become infected, return home, and develop symptoms,” he says. “In many countries outside of Western Africa, doctors who are unfamiliar with LF mistake it for malaria and treat it as such. When that fails, it is usually too late by the time they realize what the disease is.”