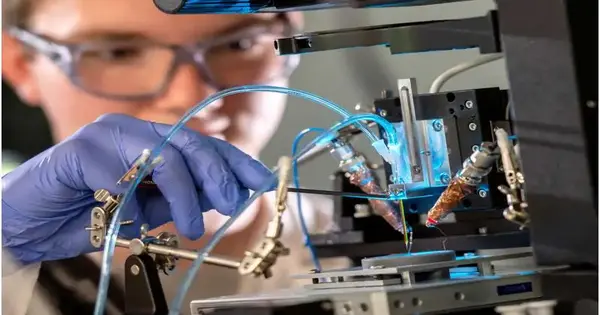

It takes physicist Liaisan Khasanova under a moment to transform a common silica glass tube into a printing spout for a unique 3D printer. The scientist embeds the slim cylinderndwhich is only one millimeter thick sinto a blue gadget, closes the fold, and presses a button. Following a couple of moments, there is a noisy bang, and the spout is ready for use.

“A laser bar inside the gadget warms up the cylinder and pulls it apart. Then we unexpectedly increase the ductile power, causing the glass to break in the center and form a sharp tip structure,” explains Khasanova, who is working on her Ph.D. in science at the Electrochemical Nanotechnology Gathering at the University of Oldenburg in Germany.

Khasanova and her partners need the little spouts to print amazingly small, three-layered metallic designs. This implies the spouts’ openings should be similarly small—at times so small that a single particle can just barely get through. “We are attempting to take 3D printing to its innovative cutoff points,” says Dr. Dmitry Momotenko, who drives the lesser exploration bunch at the Foundation of Science. His objective was: “We need to gather objects iota by particle.”

Various applications

According to the physicist, nanoscale 3D printing—that is, 3D printing of items that are only a few billionths of a meter in size—opens up incredible possibilities.For metal items specifically, he can imagine various applications in regions like microelectronics, nanorobotics, sensors, and battery innovation: “Electroconductive materials are required for a wide range of uses here, so metals are the ideal arrangement.”

“On the one hand, we are working on the chemistry required to manufacture active electrode materials at the nanoscale; on the other side, we are attempting to adapt printing technology to these materials.”

Dr. Dmitry Momotenko, who leads the junior research group at the Institute of Chemistry.

While 3D printing of plastics has previously progressed into these nanoscale aspects, producing small metal items utilizing 3D innovation has proven more troublesome. For some methods, the printed structures are still too large for the majority of advanced applications, while for others, producing the items with the required level of purity is unthinkable.

Momotenko works in electroplating, a part of electrochemistry where metal particles suspended in a salt arrangement are carried into contact with an adversely charged cathode. The decidedly accused particles join electrons to shape unbiased metal iotas, which are kept on the cathode, framing a strong layer.

“A fluid salt arrangement turns into a strong metal—aa cycle over which we electrochemists have some control, really,” says Momotenko. This equivalent cycle is utilized for chrome-plating vehicle parts and gold-plating gems for a bigger scope.

Somewhat more modest than expected

In any case, moving it to the nanoscopic scale requires extensive creativity, exertion, and care, as a visit to the gathering’s little lab on the college’s Wechloy grounds affirms. The lab contains three printers—all fabricated and modified by the actual group, as Momotenko brings up. Like other 3D printers, they comprise a print spout, tubes for taking care of the print material, a control system, and mechanical parts for moving the spout. Yet in these printers, everything is somewhat more modest than expected.

A hued saline arrangement moves through fragile cylinders into the slim, fine cylinder, which thus contains a hair-dainty piece of wire—tthe anode. It shuts the circuit with the adversely energized cathode, a gold-plated silicon chip more modest than a fingernail, which is likewise the surface on which the printing happens. Micromotors and unique gems that transform quickly when an electrical voltage is applied quickly move the spout by parts of a millimeter in each of the three spatial headings.

Since even the smallest vibrations can upset the printing system, two of the printers are housed in an enclosure covered in a thick layer of dimly hued acoustic froth. Besides, they are lying on rock plates, each weighing 150 kilograms. The two measures are aimed at forestalling undesirable vibrations. The lights in the lab are likewise battery-fueled on the grounds that the electromagnetic fields created by rotating flow from an attachment would impede the small electrical flows and voltages expected to control the nanoprinting system.

An outing into the nanoworld

In the mean time, Liaisan Khasanova has arranged everything for a test print: the print spout is in its beginning position, the case is shut, and a vial containing a light blue copper arrangement is associated with the cylinders. She begins a program, which starts the printing system. Estimation information shows up on a screen as bends and dabs. These show the varieties in the ongoing stream and register the spout momentarily contacting the substrate and afterward withdrawing over and over. What is the machine printing? “Only a couple of segments,” she answers.

Segments are the easiest mathematical structures created in 3D printing, yet the Oldenburg analysts can likewise print twistings, rings, and a wide range of overhanging structures. The method can right now be utilized to print with copper, silver, and nickel, as well as nickel-manganese and nickel-cobalt amalgams. In a portion of their tests, they have previously wandered profoundly into the nanoworld. Momotenko and a global group of scientists detailed in a review distributed in the journal Nano Letters in 2021 that they had created copper sections with a width of only 25 nanometers, interestingly taking 3D metal printing beneath the 100-nanometer limit.

One of the foundations for this achievement was an input system that empowered accurate control of the print spout’s developments. It was created by Momotenko along with Julian Hengsteler, a Ph.D. understudy he managed at his past work environment, ETH Zurich in Switzerland. “The nonstop withdrawal of the print spout is hugely significant, on the grounds that if not, it would immediately become obstructed,” makes sense to the scientist.

“A fluid salt arrangement turns into a strong metal—aa cycle over which we electro-scientists have some control, really.”

The group prints the small items layer by layer at a pace of a couple of nanometers per second. Momotenko actually finds it astounding that objects too small to ever be apparent to the natural eye are being made here. “You start with an item you can contact.” “Then a specific change happens, and you can handle these undetectable things at a very limited scale—it is practically fantastic,” says the scientist.

An e-vehicle can be charged quickly.

Momotenko’s arrangements for his nanoprinting method are likewise stunning: he wants to lay the groundwork for batteries that can be charged multiple times faster than current models. “If that can be accomplished, you could charge an e-vehicle in no time,” he explains.The essential thought he is seeking is now around 20 years old. The rule is to radically abbreviate the pathways of the particles inside the battery during the charging system.

To do this, the cathodes, which are right now flat, would have to have a three-layered surface design. “With the ongoing battery configuration, charging takes such a long time on the grounds that the cathodes are somewhat thick and far apart,” Momotenko makes sense of.

According to the arrangement, he is to interlock the anodes and cathodes like fingers at the nanoscale and reduce the distance between them to only a couple of nanometers. This would permit the particles to move among the anode and cathode at lightning speed. The problem is that it has not been possible to create battery structures with the required nano aspects thus far.

Momotenko has now taken this test. In his NANO-3D-LION project, the objective is to create and utilize advanced nanoscale 3D printing methods to manufacture dynamic battery materials with ultrasmall primary elements. Having teamed up effectively with an exploration bunch led by Prof. Dr. Gunther Wittstock at the Foundation of Science in a prior project, Momotenko then chose to base the task at the College of Oldenburg. “The Division for Exploration and Move was useful with my award application, so I moved here from Zurich toward the start of 2021,” he makes sense of.

His examination group now has four members: in addition to Khasanova, Ph.D. understudy Karuna Kanes and Expert’s understudy Simon Sprengel have joined the group.Kanes centers around another strategy pointed toward upgrading the accuracy of the print spout, while Sprengel examines the chance of printing mixes of two unique metals—a cycle important to create cathode and anode material at the same time in one stage.

Liaisan Khasanova will soon zero in on lithium compounds. Her main goal will be to figure out how the anode materials currently utilized in lithium batteries can be organized using 3D printing. The group is wanting to examine mixtures, for example, lithium-iron or lithium-tin, and then test how huge the nano “fingers” on the anode surfaces should be, what dividing is doable, and the way that the cathodes ought to be adjusted.

Dealing with highly receptive lithium

One significant obstacle here is that lithium compounds are profoundly receptive and must be dealt with under controlled conditions. Thus, the group as of late has gained an extra-huge form of a lab glove box: a gas-tight fixed chamber that can be loaded up with an idle gas like argon. It has gloves incorporated into one side with which the analysts can control the articles inside.

The chamber, which is around three meters in length and weighs a portion of a ton, isn’t yet in use, but the group intends to set up one more printer inside it. “The compounding change of the material and any remaining tests will likewise be done inside the chamber,” Momotenko makes sense of.

The group will face a few significant inquiries over the task: How do small pollutants inside the argon air influence the printed lithium nanostructures? How do you disperse the intensity that is undoubtedly created when batteries are quickly charged? How to print small battery cells as well as large batteries in a reasonable amount of time to power a cell phone or even a vehicle.

“From one viewpoint, we are dealing with the science expected to create dynamic anode materials at the nanoscale; from another, we are attempting to adjust the printing innovation to these materials,” says Momotenko, framing the ongoing difficulties.

The scientist emphasizes that the issue of energy stockpiling is very perplexing, and his group can have only a minor impact on resolving it.Regardless, he sees his gathering in a decent beginning position: as he would see it, electrochemical 3D printing of metals is as of now the main feasible choice for assembling nanostructured cathodes and testing the idea.

Despite battery innovation, the physicist is likewise dealing with other strong ideas. He needs to utilize his printing method to create metal designs that consider a more designated control of compound responses than has been possible up to this point. Such plans assume a part in a somewhat youthful field of examination known as spintronics, which centers around the control of “turn,” a quantum mechanical property of electrons.

Another idea he has is to create sensors that can identify individual atoms.”That would be useful in medication, for identifying cancer markers or biomarkers for Alzheimer’s at very low focus, for instance,” says Momotenko.

This multitude of thoughts is still a new methodology in science. “It isn’t yet clear how it would all work,” he concedes. But that is how science works: “Each significant exploration project requires long reasoning and arranging, and in the end, most ideas fizzle,” he concludes.Yet, at times, they don’t, and he and his group have previously made the most fruitful strides on their excursion.

Provided by University of Oldenburg