As part of the response to the BP oil spill, chemical dispersants were sprayed in unprecedented quantities in the Gulf. The toxic effects of these dispersants on marine life and humans serve as yet another example of the hazardous environmental consequences of offshore oil drilling and why it must be stopped. Chemical dispersants are among the most effective tools for cleaning up after an oil spill. However, scientists do not fully comprehend how well they function. A new study confirmed their effectiveness in better preparing for the next disaster.

Marine oil spills are one of the most visible and harmful examples of the environmental impact of fossil fuel extraction. Chemical dispersants, which break down oil in water, are one of the few tools available to help mitigate the damage. However, scientists do not fully understand how well they work. A new study led by Bigelow Laboratory validated their efficacy under real-world conditions in order to better prepare for the next disaster.

“We don’t want to just apply chemicals to the ocean without fully understanding what happens,” said Senior Research Scientist Christoph Aeppli, lead author on the study. “We want to know that dispersants are as effective as they can be to help ecosystem recovery.”

Oil spills are still going to be happening for a while. Ships are going to be powered by fossil fuel for a long time and goods still need to be transported. Decarbonizing the economy will take time. Until then, we need to make sure we know how to best respond to any oil spill that can happen.

Christoph Aeppli

Oil spills impact life at every level of the ocean food web, and emergency response efforts must move quickly to minimize the damage after they occur. Crews could wait until oil washes ashore to clean it up, but its toxic compounds can persist for decades and damage sensitive ecosystems.

Chemical dispersants can be used to address spills at sea by breaking oil into small droplets that get mixed into the water and diluted rapidly. When dispersants are applied, oil typically persists in the water column for much less time than they would on shore even though oil droplets temporarily increase the toxicity in the water. However, adding additional chemicals to the environment has been controversial.

Previous laboratory research after the 2010 Deepwater Horizon oil spill cast some doubt about the effectiveness of dispersants and illuminated their risks. Further work was needed to assess these laboratory results in the environment. Aeppli, alongside partners from the industry, set out to test dispersants using real-world conditions to understand their full impact on ecosystems.

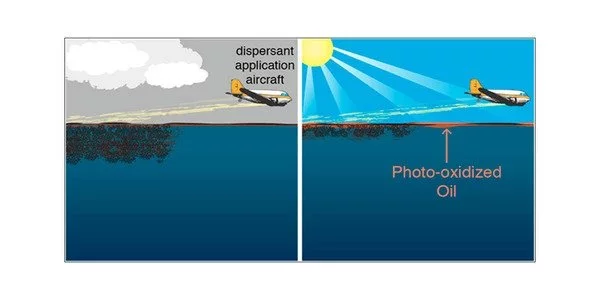

Oil becomes more viscous through exposure to sunlight and other environmental factors. Higher viscosity potentially limits the effectiveness of dispersants. The researchers used large test chambers to isolate seawater in the environment and run experiments in real-world conditions.

“Ideally, you would want to run tests in the field but, of course, there are a lot of reasons you cannot just make an oil spill at sea and measure that,” Aeppli said. “So, we constructed large pools of seawater and let natural sunlight oxidize the oil rather than doing everything on the lab bench in artificial conditions.”

They concluded chemical dispersants were still effective under normal oil spill conditions even though environmental factors rapidly increased oil viscosity and how it disperses. The results suggested that dispersants were effective if applied within two to four days – a typical time frame for oil spill response as recommended by current guidelines.

The researchers also compared their results to field data collected from the Deepwater Horizon spill, which confirmed their laboratory findings. After the spill, almost 1 million gallons of dispersants were used over 90 days of continuous operations. Over 75% of field measurements showed effective dispersion, suggesting that previous laboratory tests had underestimated dispersants’ effectiveness.

This research is part of Aeppli’s efforts to investigate the impact of toxins on the environment. He hopes his work helps society mitigate the damage of oil spills as it works to transition to renewable energy.

“Oil spills are still going to be happening for a while,” Aeppli said. “Ships are going to be powered by fossil fuel for a long time and goods still need to be transported. Decarbonizing the economy will take time. Until then, we need to make sure we know how to best respond to any oil spill that can happen.”