Tremendous amounts of minerals are expected to speed up the progress toward a spotless energy future. Minerals and metals are fundamental for wind turbines, sunlight-powered chargers, and batteries for electric vehicles. However, Native American groups have expressed concern about additional mining on their lands and in their communities.

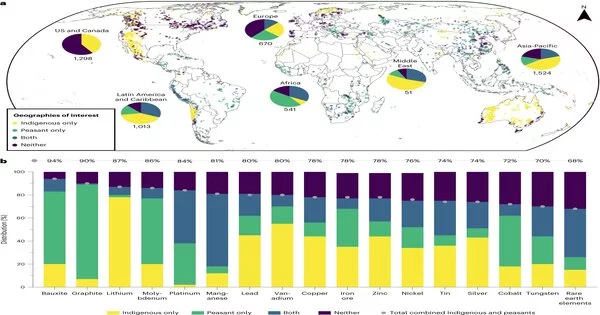

Another review, led by creators John Owen and Deanna Kemp and published in Nature Maintainability on December 1, defends the interests of First Nations people groups.We recognized 5,097 mining projects, including around 30 minerals required for energy progress. 54% are located on or near the territories of Native American tribes.

These lands are important both environmentally and socially.Their dirt and land cover, for example, woodlands, store carbon, which assists with managing the planet’s environment. Typically, the terrains are also natural for the personalities and lifestyles of Native people groups.

Energy progress and minerals are fundamental to handling environmental change. Individuals from First Nations countries, on the other hand, should have a legal say in where and how they are separated.

At the point when minerals and networks impact

According to the World Energy Organization, lithium demand for electric vehicle batteries will more than triple by 2040.Our review discovered that 85% of the world’s lithium stores and assets overlap with the properties of Native people groups.

Interest in nickel and manganese is projected to grow 20–25 times. We saw that 75% of manganese and 57% of nickel stores and assets likewise crossed over on these grounds.

Copper and iron minerals, as well as their transportation, storage, and use, are critical for the power age.A few situations foresee an expansion in copper interest of over 100% by 2050. We saw 66% of the world’s copper and 44% of its iron stores and assets cross over with Native people groups’ lands internationally.

Generally speaking, across the 5,097 ventures in our review, 54% are on or close to Native people groups’ properties. Furthermore, nearly 33% are on or near lands over which Native American groups are perceived to have control or an impact for protection purposes.

Free, earlier, and informed assent

Last year, at the COP26 Joined Countries Environmental Change Meeting, Native gatherings and people from around the world made a statement to environment moderators to focus on obtaining progress minerals more reliably.

They also approached legislatures and organizations to obtain Native people groups’ “free, prior, and informed consent” in decisions that affect them.

This sort of assent is cherished in the United Nations Announcement on the Freedoms of Native People Groups. It implies that indigenous peoples should have the option to accept or reject mining on their traditional lands, as well as to set conditions such as safeguarding natural and social legacies.

Mining has enormously complex repercussions and can cause serious damage to social orders, the climate, and basic liberties. Meeting and consent processes take time. Organizations and legislatures attempting to extract assets in a hurry are likely to fail to engage with networks genuinely.

When new mining projects are optimized, a significant number of corners are cut.Without legitimate meetings and legal securities, the future stock of progress minerals may endanger Native people groups’ properties.

Feeble regulations should be reinforced.

Australia has a remarkable record of preserving Native heritage and obtaining assent.

Rio Tinto destroyed 46,000-year-old Native stone sanctuaries in May 2020 to mine iron metal, despite the wishes of traditional owners and the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura people groups.

The customary proprietors said the obliteration was a misfortune for their kin, all Australians, and humankind. Alarmingly, the annihilation was legitimate.

Last week, answering a government parliamentary investigation into the Juukan Chasm episode, Climate Pastor Tanya Plibersek said the obliteration of the stone havens was “totally off-base.” She recognized the enormous power disparity that occurs when traditional proprietors bargain with mining organizations, as well as the lack of assets from which they can draw.

Plibersek said lawful change is earnestly expected to stop such obliteration from reoccurring. In this vein, the region has consented to an arrangement with the Principal Countries Legacy Assurance Union to co-plan new social legacy regulations.

Drives like Dhawura Ngilan (Recollecting Nation) set an aggregate vision for best-practice legacy principles and regulation. Organizations and financial backers ought to apply these conventions while our regulations get up to speed.

Meanwhile, other legacy locales in Western Australia are undermined by existing development endorsements. The new Native Social Demonstration actually endows the priest with extraordinary power to determine the fate of Native peoples.

Native pioneers remain profoundly worried that shocking occurrences, such as Juukan Canyon, could reoccur.

What does the future hold?

To avoid a double environmental and social disaster, first-country groups in Australia and elsewhere are banding together and making their voices heard on the global stage.

At the current year’s COP27 environment meeting, the Worldwide Native People groups Gathering on Environmental Change facilitated a Native structure in the “blue zone,” where supporters accumulate to organize and examine significant issues. Such global First Country fortitude is becoming increasingly important in the fight against climate change and achieving equitable energy progress.

Native peoples should approach the most recent information and data with caution, keeping in mind the future mineral abundance in their territories.This is a practical step toward controlling one’s awkward nature.

Answers to the environmental emergency should be found, and energy progress and minerals are a significant piece of the puzzle. Notwithstanding, First Nations’ desires for keeping up with the normal and social respectability of their properties and regions and partaking in choices about mining should be at the forefront.

More information: John R. Owen et al, Energy transition minerals and their intersection with land-connected peoples, Nature Sustainability (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41893-022-00994-6

Journal information: Nature Sustainability