For quite a long time, stargazers and physicists have been attempting to settle perhaps the most profound secret about the universe: that 85% of its mass is missing. Various cosmic perceptions show that the apparent mass known to man isn’t sufficiently large to keep worlds intact and represent how matter bunches. Some sort of undetectable, obscure kind of subatomic molecule, called dim matter, should give the extra gravitational field.

For over 30 years, researchers have been looking for this dim matter in underground labs and at molecule gas pedals with no success.Analysts at NIST are presently investigating better approaches to look for the undetectable particles. In one review, a model for a much bigger trial, scientists have utilized cutting-edge superconducting finders to chase after dim matter.

The review has previously put new cutoff points on the conceivable mass of one sort of dim matter. Another NIST group has proposed that caught electrons, which are typically used to assess the properties of common particles, could also act as extremely sensitive detectors of speculative dim matter particles if they carry charge.

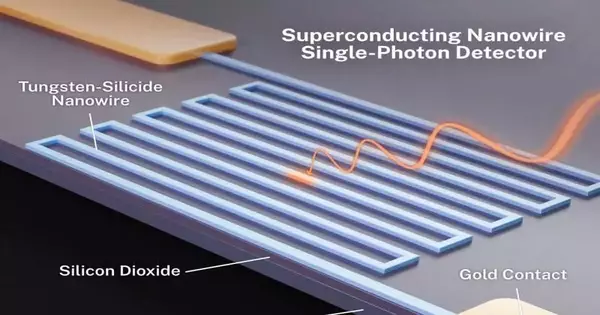

In the superconducting finder study, NIST researchers Jeff Chiles and Sae Charm Nam and their partners utilized tungsten silicide superconducting nanowires only one-thousandth the width of a human hair as dim matter locators.

“Superconducting” alludes to a property that a few materials, like tungsten silicide, have at ultralow temperatures: no protection from the progression of electrical flow. Frameworks of such wires, officially known as “superconducting nanowire single-photon finders” (SNSPDs), are perfectly delicate to very modest quantities of energy granted by photons (particles of light) and maybe dim matter particles when they slam into the locators.

Electron movement as a method of identifying dim matter particles.

Scientists work with SNSPDs at temperatures just below the temperature required for the nanowires to become superconducting. Like that, even a small measure of energy held by an approaching molecule will create sufficient intensity to foster electrical opposition in the wire.

With the progression of flow through the nanowire now blocked, the flow goes along a subsequent path associated with an electrical speaker. The current creates a brief yet quantifiable voltage—a transmission that warmed up a piece of the nanowire by connecting with a photon or, maybe, a dim matter molecule.

The SNSPD experiment was made up of a small square cluster of nanowires, each 140 nanometers (nm, or billionths of a meter) wide and divided by 200 nm, kept in a light-close box.The scientists added a heap of two kinds of protecting materials, intended to make it more probable that the framework could look for a sort of speculative dim matter molecule known as a dim photon.

As per hypothetical forecasts, a dim photon crashing into the stack would probably destroy itself and create a normal infrared photon in its place. A focal point would then concentrate the photon onto the SNSPD circuit, where it could connect with the nanowires and be identified as a voltage signal.

The little, 180-degree extended try tracked down no proof of dim photons in the low-mass scope of 0.7 to 0.8 electron volts/c2 (eV/c2), not exactly a portion of a millionth the mass of the electron, the lightest known stable molecule. (Because the majority of subatomic particles are too small to be usefully communicated as far as a small portion of a kilogram, physicists generally use the meaning of mass in Einstein’s E=mc2.)

Although the trial would need to be repeated with a larger scope and more finders to provide a larger dataset, Nam claims that it is the most delicate search for dim photons performed to date in this mass reach.The scientists, including partners from the Massachusetts Foundation for Innovation, Stanford College, the University of Washington, New York College, and the Flatiron Organization, detailed their outcomes in an article in Actual Audit Letters.

In a subsequent report, a portion of similar NIST scientists and their partners examined information from the main concentrate another way. The researchers overlooked the likely impacts of the pile of protecting material and zeroed in just on whether any sort of dim matter particles would be fit for connecting with individual electrons in the nanowire finder itselfroeither by dispersing an electron or being consumed by it.

Albeit little, this study has put the most grounded constraints of any trial to date—bbarring astrophysical hunts and investigations of the sun—oon the strength of connections among electrons and dim matter in the sub-million-eV mass range. That makes it likely that an increased variant of the SNSPD arrangement could make a huge commitment to the quest for dim matter, said Chiles.

He and his partners from the Jewish College of Jerusalem, the College of California’s St. Nick Cruz Foundation for Molecule Physical Science, and MIT detailed this examination in an article in the Dec. 8 release of Actual Audit D.

In a third report, a NIST physicist and his partners suggested that solitary electrons, electromagnetically bound to a little locale of room, could be delicate finders of charged dark matter particles. For over thirty years, researchers have utilized a much heavier population of decidedly charged beryllium particles to test the electric and attractive properties of common (non-dim) charged particles.

Electrons, nonetheless, would make ideal finders for detecting dim matter particles, assuming those particles have even the smallest electric charge. This is because electrons have the least mass of any charged molecule known and are thus easily moved or pulled by the slightest electrically unsettling influence, such as a molecule with a small electric charge passing nearby.

According to NIST physicist Jake Taylor, an individual of the Joint Quantum Foundation and the Joint Place for Quantum Data and Software Engineering, research organizations between NIST and the College of Maryland, a couple of single caught electrons would be expected to identify accused dim matter particles with only 100th of the charge of an electron.

The electromagnetically caught electrons would be cooled to a small portion of a degree above outright zero to restrict the molecule’s innate jitter. Taylor, alongside Daniel Carney of the Lawrence Berkeley Public Lab in California, Hartmut Haffner of the College of California, Berkeley, and David C. Moore of Yale College, depicted their proposed experiment in an actual survey letter.

By arranging the snare so that the strength of the electron’s control varies along each dimension—length, width, and level—the snare may also provide information about the direction from which the dim matter molecule appeared.

In any case, researchers should wrestle with a mechanical test before they can utilize electron catching to look for dim matter. Photons are utilized to cool, control, and sense the movement of captured particles and electrons. For beryllium particles, those photons—created by a laser—fall within the scope of noticeable light.

The innovation that empowers apparent light photons to control captured beryllium particles is deeply rooted. Conversely, the photons expected to detect the movement of single electrons have microwave energies, and the vital location innovation still can’t seem to be idealized. Nonetheless, assuming interest in the task is sufficient, researchers could foster an electron trap fit for identifying dim matter in under five years, Carney assessed.

In another review, a NIST scientist and a global gathering of partners are looking past Earth to chase after dim matter. A group that incorporates Marianna Safronova of the College of Delaware and the Joint Quantum Foundation has suggested that another age of nuclear clocks, introduced on a rocket that would fly nearer to the sun than Mercury’s circle, could look for indications of ultralight, dim matter.

This speculative sort of dim matter, bound to a corona encompassing the sun, would cause small variations in the key constants of nature, including the mass of the electron and the fine design constant.

Changes in these constants would modify the recurrence at which nuclear clocks vibrate—tthe rate at which they “tick.” Among the huge assortment of nuclear clocks, analysts would cautiously pick two that have various aversions to changes in the key constants driven by ultra-dim matter. By estimating the proportion of the two shifting frequencies, researchers could uncover the presence of the dim matter, the analysts determined.

They depict their examination in an article posted online in Nature Cosmology.

More information: Jeff Chiles et al, New Constraints on Dark Photon Dark Matter with Superconducting Nanowire Detectors in an Optical Haloscope, Physical Review Letters (2022). DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.128.231802

Daniel Carney et al, Trapped Electrons and Ions as Particle Detectors, Physical Review Letters (2021). DOI: 10.1103/PhysRevLett.127.061804

Yu-Dai Tsai et al, Direct detection of ultralight dark matter bound to the Sun with space quantum sensors, Nature Astronomy (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41550-022-01833-6