Wonder about the little nanoscale structures rising up out of examination labs at Duke College and Arizona State College, and it’s not difficult to imagine you’re perusing an index of the world’s tiniest ceramics.

Another paper uncovers a portion of the groups’ manifestations: itty-bitty jars, bowls, and empty circles, one secret inside the other, as housewares for a Russian settling doll.

Yet, rather than making them from wood or mud, the analysts planned these items out of threadlike atoms of DNA that bowed and collapsed into complex three-layered objects with nanometer accuracy.

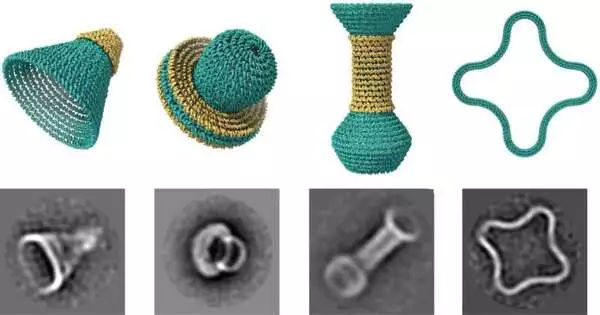

These manifestations show the potential outcomes of another open-source programming program created by Duke Ph.D. undergrad Dan Fu and his guide John Reif. As depicted on December 23 in the journal Science Advances, the product allows clients to take drawings or computerized models of adjusted shapes and transform them into 3D designs made of DNA.

The DNA nanostructures were gathered and imaged by co-creators Raghu Pradeep Narayanan and Abhay Prasad in teacher Hao Yan’s lab at Arizona State. Each small empty item is something like two millionths of an inch across. More than 50,000 of them could fit on the top of a pin.

Yet, the analysts say these are more than simple nanomodels. The product could permit analysts to make small holders to convey medications or molds for projecting metal nanoparticles with explicit shapes for sun-based cells, clinical imaging, and different applications.

To the vast majority, DNA is the plan of life—the hereditary guidelines for every living thing, from penguins to poplar trees. Yet, to groups like Reif’s and Yan’s, DNA is more than a transporter of hereditary data—it’s source code and development material.

There are four “letters,” or bases, in the hereditary code of DNA, which match up in an anticipated way in our cells to frame the rungs of the DNA stepping stool. It’s these severe base-matching properties of DNAtaA with T and C with Gh that the scientists have co-opted. By planning DNA strands with explicit groupings, they can “program” the strands to sort themselves out into various shapes.

The strategy entails collapsing one or two long strands of single-stranded DNA, many bases long, with the assistance of two or three hundred short DNA strands that tight spot reciprocal groupings on the long strands and “staple” them together.

Scientists have been trying different things with DNA as a development material since the 1980s. The main 3D shapes were basic 3D squares, pyramids, and soccer ballsntmathematical shapes with coarse and blocky surfaces. Yet, planning structures with bowed surfaces more similar to those found in nature has been precarious. The group’s point is to expand the scope of shapes that are conceivable with this strategy.

That’s what to do. Fu created programming called DNAxiS. The product depends on DNA to work, as depicted in 2011 by Yan, who was a postdoc with Reif at Duke a long time ago prior to joining the staff at Arizona State. It works by looping a long DNA double helix into concentric rings that stack on top of one another to form the shapes of the item, such as using mud curls to make a pot.To strengthen the designs, the group made it possible to support them with additional layers for increased security.

Fu flaunts the range of structures they can make: cones, gourds, and clover leaf shapes. DNAxiS is the primary programming device that enables clients to naturally configure such shapes, utilizing calculations to determine where to place the short DNA “staples” to join the more DNA rings together and hold the shape in place.

“Assuming there aren’t excessively many, or, on the other hand, in the event that they’re in some unacceptable position, the design won’t shape accurately,” Fu said. “Before our product, the arch of the shapes made this a particularly troublesome issue.”

Given a model of a mushroom shape, for instance, the PC lets out a rundown of DNA strands that would self-assemble into the right setup. When the strands are blended and blended in a test tube, the rest takes care of itself: by warming and cooling the DNA combination, inside just 12 hours “it kind of mystically overlaps up into the DNA nanostructure,” Reif said.

According to the analysts, useful applications of their DNA plan programming in the lab or center could be years away. Yet, “it’s a major forward-moving step regarding the robotized design of novel three-layered structures,” Reif said.

More information: Daniel Fu et al, Automated Design of 3D DNA Origami with Non-Rasterized 2D Curvature, Science Advances (2022). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.ade4455. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.ade4455

Journal information: Science Advances