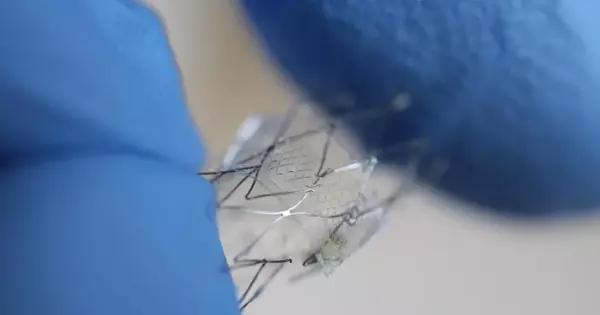

Researchers are improving patients’ chances by developing an implantable soft electronic vascular monitoring system. Their smart stent and printed soft sensors are capable of wireless real-time hemodynamic monitoring without the use of batteries or circuits.

Vascular diseases are the public enemy number one: the leading killers on the planet, accounting for nearly one-third of all human deaths. Continuous hemodynamic monitoring (blood flow through the vascular system) can improve treatments and patient outcomes. However, life-threatening conditions such as hypertension and atherosclerosis occur in a long and twisting vascular system with arteries of varying diameter and curvature, and existing clinical devices are limited in their bulk, rigidity, and utility.

Woon-Hong Yeo, a researcher at Georgia Institute of Technology, and his colleagues are attempting to improve the odds for patients by developing an implantable soft electronic monitoring system. Their new device, which consists of a smart stent and printed soft sensors, is capable of wireless real-time hemodynamic monitoring without the use of batteries or circuits.

Basically, you can put this sensor system anywhere inside the body. The other thing about this technology platform is, in addition to being an implantable sensor system, it can be used as a wearable system. Think about a smartwatch and how much of its bulk is taken up by circuits or batteries. If you remove all of that, you have a device that is thinner than a typical Band-Aid, an almost invisible health monitor that you can wear anywhere.

Woon-Hong Yeo

“This electronic system is designed to wirelessly deliver hemodynamic data, including arterial pressure, pulse, and flow, to an external data acquisition system, and it is super small and thin, which is why we can deliver it anywhere inside the body,” said Yeo, whose team published their findings in the journal Science Advances.

Yeo added, smiling, “It’s like a stent with multiple tricks up its sleeve.”

For example, when this device is installed in a patient with atherosclerosis, in addition to expanding and preventing the artery from narrowing, like a traditional stent, restoring normal blood flow, it will also provide a constant flow of data.

“Now, once you have deployed a stent, you’re not sure if the problem was resolved and patients may come back with the same issue,” Yeo said. “It can be a defect of the stent, or an issue with stent deployment, or perhaps a problem with the patient’s blood flow.”

And the current standard way to monitor all of that is with an angiogram. That can be expensive and in rare instances, particularly with patients also struggling with diabetes, the dyes and radiation used in angiogram imaging can cause cancer. Yeo’s system seeks to circumvent the need for an angiogram or other imaging requirements.

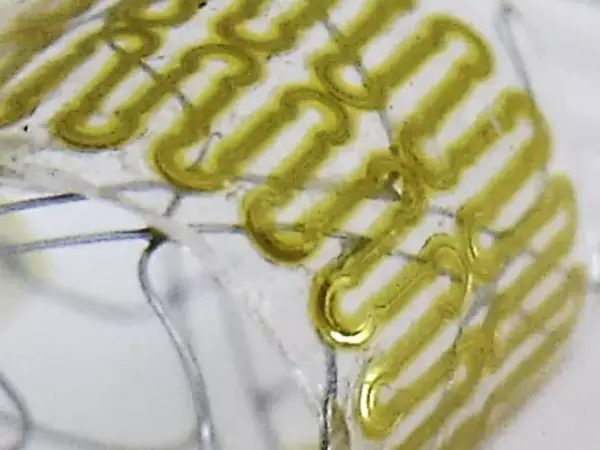

His wireless smart stent platform, integrated with soft sensors, is operated by inductive coupling to offer wireless real-time monitoring that can detect a wide range of vascular conditions. Inductive coupling uses magnetic fields for wireless energy transfer. It’s similar to what’s happening when you use a wireless charger for your phone, smartwatch, or other devices – they are gaining energy from the magnetic field created by the charger.

“Basically, you can put this sensor system anywhere inside the body,” Yeo explained. “The other thing about this technology platform is, in addition to being an implantable sensor system, it can be used as a wearable system. Think about a smartwatch and how much of its bulk is taken up by circuits or batteries. If you remove all of that, you have a device that is thinner than a typical Band-Aid, an almost invisible health monitor that you can wear anywhere.”

That’s the long-range goal, anyway. So far, they’ve tested their wireless implantable system on animal models. However, there is still plenty of work to do. And Yeo also has the backing of the National Science Foundation to advance the technology. He recently received a 3-year, $400,000 grant from NSF focused on his printed nanomembrane sensors and bioelectronics for wireless and continuous monitoring of vascular health.

“We believe that the mechanical, material, and electrical design principles we develop, and the engineering and biosensing framework that results from this work, will advance the field of implantable electronics and biomedical systems,” Yeo said. “And the insights and knowledge we gain will be applicable for other physiological processes and challenges in biomedical science and engineering.”