Parasitic plants are remarkable plants with one of a kind physiology, environment, and developmental narratives, and little is known about them having some significant awareness of their starting point and advancement. At first, certain autotrophs advanced to be facultative hemiparasitic plants, which got just water and mineral supplements from their hosts as enhancements. A portion of the facultative hemiparasitic plants later became committed parasitic plants that needed to rely upon their hosts to finish their life cycles. Steadily, holoparasitic plants advanced from committing parasites, and they totally lost their photosynthesis limit.

In angiosperms, parasitic plants autonomously advance 12 or multiple times. In eight parasitic plant ancestries, hemiparasitic species became wiped out, leaving just holoparasites remaining. In any case, the Orobanchaceae (Lamiales), the biggest group of parasitic plants, contains autotrophic and parasitic plants with all levels of parasitism. This makes it, by a wide margin, the best family for concentrating on the beginning and development of plant parasitism.

“The researchers conducted the largest comparative genomics analysis of parasitic plants to date by combining these newly sequenced genomes with existing data, revealing the evolution of the orobanchaceous parasitic genomes.”

Prof. Wu Jianqiang from the Kunming Institute of Botany of the Chinese Academy of Sciences (KIB/CAS)

An investigation group led by Prof. Wu Jianqiang of the Chinese Academy of Sciences’ Kunming Institute of Botany (KIB/CAS) has recently sequenced and commented on the reference genomes of orobanchaceous plants, the autotroph Lindenbergia luchensis, and two economically significant holoparasitic bugs, Orobanche cumana and Phelipanche aegyptiaca.Important outcomes were distributed in Molecular Plants.

Plant species in the family Orobanchaceae traverse from non-parasitic to expanding levels of parasitism.

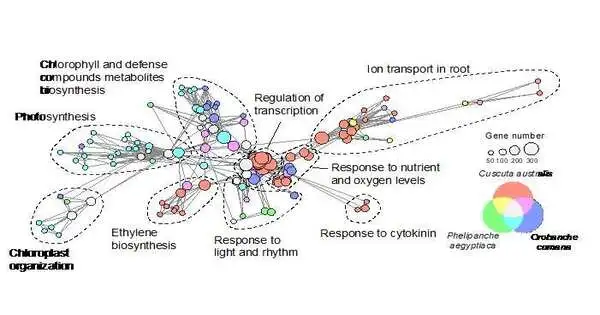

By joining these recently sequenced genomes with existing information, the scientists carried out the biggest similar genomics investigation of parasitic plants to date, revealing the development of the orobanchaceous parasitic genomes.

The specialists tracked down that, not at all like dodder, orobanchaceous parasitic plants didn’t go through an emotional withdrawal in genome size and quality. All things being equal, both hemiparasitic and holoparasitic orobanchaceous plants had bigger genomes and a greater number of qualities than the autotrophic Lindenbergia luchensis.

The haustorium is a one-of-a-kind organ in parasitic plants that empowers them to lay out an actual association with their hosts so they can live parasitically. Utilizing haustorium transcriptome information, the analysts recognized haustorially exceptionally communicated qualities in the genomes of different parasitic plants and found that these qualities likewise went through sensational extensions.

There are two striking times of quality developments; one brought about by a paleopolyploidy occasion (L occasion, around 73.48, quite a while back, before the rise of parasitism), and the other was brought about by a free duplication after the dissimilarity of each parasitic plant. Examination with the unbiased model uncovered that the L occasion assumed a significant part in the beginning of the haustorium in spite of the fact that it occurred around 35 million years before the beginning of parasitism.

Quality family transformative examination uncovered that these parasitic plants went through synchronous quality family compression and extension in their genomes. Quality misfortune increased as parasitism level increased: from around 2-3% quality misfortune in facultative hemiparasites to around 6-7% quality misfortune in commit hemiparasites and around 13-15% quality misfortune in holoparasites.

The majority of the characteristics lost in the Orobanchaceae were indistinguishable from those lost in dodder, a parasitic plant with something entirely different. The majority of these qualities are connected with photosynthesis and chloroplast capability.

The differential quality misfortune was primarily connected with the two different parasitic structures; stem parasitism and root parasitism, with orobanchaceous plants losing more qualities connected with photosynthesis as well as light motion, while dodder losing more qualities connected with root organ capability.

Consequences of this study support a three-stage model of parasitic plant genome development: first, improvement of the haustorium, which empowered an actual association with host plants; second, after the haustorium had developed, the parasites began to lose qualities that were not generally required; and third, the parasites advanced to adjust to their particular hosts.

More information: Yuxing Xu et al, Comparative genomics of orobanchaceous species with different parasitic lifestyles reveals the origin and stepwise evolution of plant parasitism, Molecular Plant (2022). DOI: 10.1016/j.molp.2022.07.007

Journal information: Molecular Plant