With energy costs rising, and the rapidly emerging effects of burning fossil fuels on the global climate, the need has never been greater for researchers to find paths to products and fuels that are truly renewable.

“We use 20 million barrels of oil a day in the U.S.; that’s about a fifth of the world’s usage,” said Ned Jackson, a professor of organic chemistry in the College of Natural Science at Michigan State University. “All our liquid fuels and nearly all of our manufactured materials, from gasoline and gallon jugs to countertops and clothes, start with petroleum — crude oil.”

Developing the tools to move from fossil fuels to renewable sources of carbon for all these components of daily life is necessary. But according to the most optimistic projections, Jackson said, “What we could harvest annually from biomass in the U.S. only has about two-thirds as much carbon in it as the crude oil that the nation uses.”

Jackson and his former graduate student Yuting Zhao, now a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Illinois, have developed a chemical method that enables electricity and water to break the strong chemical bonds in biomass or plant matter. This “electrocatalytic” process could be applied to lignin, a carbon-rich biomass component that is usually discarded or simply burned as a byproduct of making paper. This new tool also has the potential to destroy environmental pollutants.

The research was published in the journal Nature Communications.

One of the things that drives us is the idea that our main use of petroleum is fuel that is burned to produce energy, adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere. The new science is a step toward extracting useful carbon compounds to displace some fraction of the fossil petroleum that we use today.

Ned Jackson

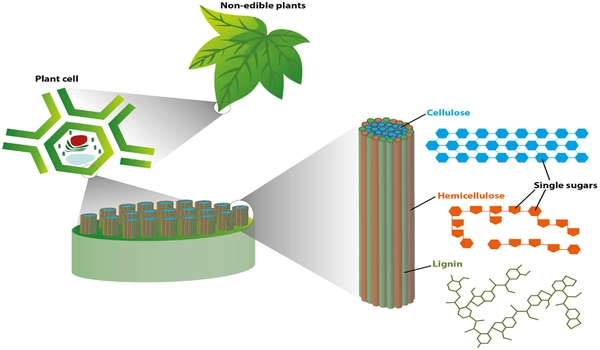

A global goal is to tap into both the carbon and the energy stored in biomass to enable it to replace petroleum. But new, efficient methods are needed to break this complex, tough, low-energy material down into the building blocks for fuels and products. Specifically, tools are needed to disconnect the strong chemical bonds that bind it together, while retaining – and even enhancing – as much of the carbon and energy content as possible.

“One of the things that drives us is the idea that our main use of petroleum is fuel that is burned to produce energy, adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere,” Jackson said. “The new science is a step toward extracting useful carbon compounds to displace some fraction of the fossil petroleum that we use today.”

Parts of this research were supported by the Great Lakes Bioenergy Research Center (GLBRC). The GLBRC is led by the University of Wisconsin-Madison and brings together over 400 scientists, engineers, students, and staff from across different disciplines from institutions like MSU. One of GLBRC’s goals is to develop sustainable biofuels.

To be able to replace petroleum, new, efficient methods for breaking down the complex, tough, low-energy material into the building blocks for fuels and products are required. The research concludes that tools are required to disconnect the strong chemical bonds that bind it together while retaining and even improving as much of the carbon and energy content as possible.

“One of the things that drive us is the idea that our primary use of petroleum is fuel that is burned to produce energy, thereby adding greenhouse gases to the atmosphere,” Jackson explained. “The new science is a step toward extracting useful carbon compounds that can displace some of the fossil petroleum that we currently use.”