Scientists in the Oregon State College School of Design have fostered a handheld sensor that tests sweat for cortisol and gives results in about eight minutes, a key development in observing a chemical whose levels are a marker for some illnesses, including different diseases.

The results were presented in ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces. According to the researchers, the new device’s material and sensing mechanism could be easily modified to detect additional specific hormones, such as progesterone, a key indicator of women’s reproductive health and pregnancy outcomes.

Larry Cheng, an associate professor of electrical engineering and computer science, stated, “We took inspiration from the natural enzymes used in blood glucose meters sold at pharmacies.” Specific enzymes are applied to an electrode in glucose meters, where they can capture glucose molecules and react with them to produce an electrical signal for detection. However, natural enzymes are unstable and have a short lifespan, making their discovery for cortisol detection challenging.”

“Specific enzymes are added to an electrode in glucose meters, where they can catch and react with glucose molecules to provide an electrical signal for detection. Unfortunately, discovering natural enzymes for cortisol detection is difficult, as natural enzymes are unstable and have a short lifespan.”

Larry Cheng, associate professor of electrical engineering and computer science.

Biochemical reactions are sparked by enzymes, which are substances made by living things. A stable, robust artificial enzyme capable of sensitive and selective cortisol sensing was developed by Cheng and Sanjida Yeasmin, a doctoral student who led the study, to overcome the difficulties posed by natural enzymes.

The adrenal glands produce the hormone cortisol. Cortisol is one of the steroid hormones, along with androgens, estrogens, and progestins, which are the body’s chemical messengers. Steroid chemicals play a part in a few physiological cycles, including the sexual cycle.

Cortisol is known as the “stress hormone” because it is released when people are under pressure and helps fight infections, maintain blood pressure, regulate blood sugar levels, and regulate metabolism.

Cortisol is advantageous for managing pressure for the time being; however, drawn-out times of high cortisol levels can destructively affect the body, like an expanded gamble of uneasiness, melancholy, and coronary illness.

Yeasmin stated, “Cortisol levels rise and fall throughout the day in a healthy individual.” They are generally higher in the first part of the day and lower around evening time; assuming you will successfully screen cortisol, quick and regular estimation is required.”

She stated that blood or urine testing in a clinic, “which requires laboratory equipment and trained personnel and takes over 30 minutes to complete the measurement,” is the most common method for determining cortisol levels. Additionally, patients frequently have to wait longer than two days for their results.

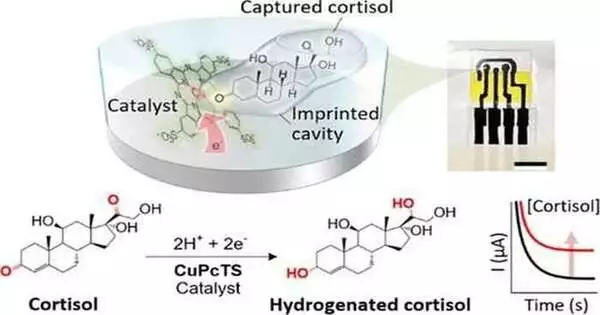

Yeasmin and Cheng developed an “enzyme mimic sensor” to solve these issues by omitting the most costly and time-consuming aspects of conventional cortisol testing.

Yeasmin stated, “This sensor does not contain any natural enzymes, labels, or redox signaling probes.” It is a robust and integrated sensor that can be used in wearable devices as well as point-of-care applications, such as at a patient’s bedside or outside of a laboratory. Our new sensor is more reliable for stress hormone monitoring because it is more selective and sensitive than the majority of reported sensors.

The counterfeit protein is an exceptional polymer with minuscule spaces formed to fit just cortisol particles. Catalysts encircle these spaces, causing cortisol to react and generate electrical signals. The amount of cortisol that is present can be determined by measuring the signals, which is an important diagnostic tool.

An adrenal disorder such as Addison’s disease, which is characterized by abdominal pain, abnormal menstrual periods, dehydration, nausea, and irritability, or Cushing’s syndrome, which can result in weight gain, mood swings, muscle weakness, and diabetes, may be indicated by cortisol levels that are either too high or too low.

Cheng stated, “The sensor can detect sweat cortisol levels within minutes, even when they are typically 10,000 times less concentrated than blood glucose levels.” This technology’s artificial enzyme opens up new possibilities for developing future health monitoring wearable sensors.”

More information: Sanjida Yeasmin et al, Enzyme-Mimics for Sensitive and Selective Steroid Metabolite Detection, ACS Applied Materials & Interfaces (2023). DOI: 10.1021/acsami.2c21980