Steven Schiff, MD, a pediatric neurosurgeon at Yale, paid Benjamin Warf, MD, a visit at the CURE Children’s Hospital of Uganda in 2007. He was taken aback by the hospital surroundings. Every day, desperate for a cure, mothers traveled from all over the country with babies whose heads were too big. All of the mothers related the same story: All of the babies were born without any problems, but within the first few weeks of their lives, they got a bad infection. Once they got better, their heads started growing quickly over a few weeks or months. Postinfectious hydrocephalus had occurred, and the mothers had no idea about it.

A debilitating neurological condition known as hydrocephalus, or “water on the brain,” is brought on by an abnormal accumulation of cerebrospinal fluid in the ventricles deep within the brain. The ventricles expand as a result of this excess fluid, putting harmful pressure on the brain’s tissues. It can occur at birth or after a brain infection or hemorrhage. There is no known treatment, and the most common reason for neurosurgery in infancy worldwide is the need to relieve pressure on the brain.

For unknown reasons, East Africa had become a hotbed of pediatric hydrocephalus, with an estimated 4,000 new cases per year in Uganda alone. Babies who did not have easy access to more advanced care frequently perished, and even those who did make it to CURE Children’s Hospital in the early stages of the disease had difficulty recovering due to the damage that the infection had already caused.

“These findings represent the culmination of decades of collaboration and provide a clear path forward for testing the impact of targeted diagnosis and treatment of Paenibacillus infections,”

Sarah Morton, MD, Ph.D., assistant professor of Assistant Professor of Pediatrics,

The magnitude of the suffering Schiff observed struck him. I am struck by how little we know about newborn infections in developing countries as a physician, scientist, and father. He would later give testimony in front of the Congressional Subcommittee on Africa, Global Health, and Human Rights. “I am concerned that one reason is that the newborn infants who die there have no political voice,” he said.

After 16 years of persistently seeking answers, the team finally identified the Paenibacillus thiaminolyticus bacteria as the cause of postinfectious hydrocephalus in Uganda in a paper published on June 14, 2023, in The Lancet Microbe.

Sarah Morton, MD, Ph.D., assistant professor of pediatrics at Harvard Medical School and co-lead author of the paper, states, “These results are the culmination of decades of collaboration and provide a clear path forward for testing the impact of targeted diagnosis and treatment of Paenibacillus infections.” She is the co-lead author of the paper.

A new frontier While the infectious agent responsible for thousands of hydrocephalic Ugandan babies eluded researchers for years, the cause of newborn infections and postinfectious hydrocephalus in developed nations is frequently well-known and less common than other causes of hydrocephalus. It was impossible to identify and characterize the bacteria because they did not grow using conventional culture techniques. Deep-freezing and storing samples at treatment sites for subsequent analysis was frequently difficult due to Uganda’s electrical grid.

In addition, it is challenging to collect sufficient blood from infants to reliably test for bacteria. Even though advanced gene sequencing techniques could be used to identify bacteria that would not grow in culture, they were both prohibitively expensive and unavailable in Uganda. The question of what was causing all of these cases of postinfectious hydrocephalus in Ugandan infants became daunting due to this combination of obstacles. But Schiff was determined to solve this mystery because he believed it could be solved.

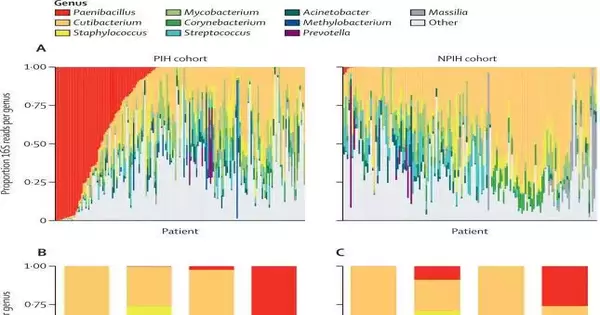

They were able to scale up their efforts after nine years of smaller, unsuccessful efforts. By 2020, Schiff’s group of researchers from Columbia and Penn State Universities discovered through genomic sequencing that an organism known as Paenibacillus thiaminolyticus, which had been thought to be harmless, was swimming in the brains of hydrocephalus infants in Uganda.

The use of blood culture bottles for cerebrospinal fluid was discovered by the researchers as a method for successfully growing some of these strains. Thanks to this, they were able to determine that the organism was resistant to the first-line antibiotics that are used to treat sick infants. Additionally, they discovered that these African strains had acquired a highly lethal and virulent toxin. These results from sequencing and culture were published in Science Translational Medicine in 2020.

The team set out to find out where the bacteria was coming from and whether it was the underlying cause of postinfectious hydrocephalus or if it was an infection that showed up in hydrocephalic infants weeks or months later but wasn’t the hydrocephalus itself. This research took place over the course of the subsequent three years.

The researchers conducted a maternal trial with 100 laboring Ugandan women from various regions. They found no evidence that the Paenibacillus bacteria was carried by the mothers or transferred to infants, despite the fact that many infections in newborns are transmitted by mothers. After that, they examined 800 newborns from various parts of Uganda who had contracted a serious infection known as sepsis. In about 6% of the cases, they did discover the Paenibacillus bacteria in this area.

Post-infectious hydrocephalus affected many of the newborns who survived the sepsis infection. Paenibacillus infection was confirmed by PCR in 44% of the 400 postinfectious cases of infant hydrocephalus. The same bacteria that caused the newborn infection and was still present when they returned for treatment weeks or months later with an enlarging head from hydrocephalus was found when the team ran PCR tests on samples of those newborns with sepsis who had developed postinfectious hydrocephalus.

The Paenibacillus infection was definitively identified as the disease that causes widespread hydrocephalus in infants and newborn deaths in papers that were published in The Lancet Microbe and Clinical Infectious Disease.

“Our results suggest that Paenibacillus is an underrecognized cause of neonatal infection,” says lead author Jessica Ericson, MD, assistant professor of pediatrics and infectious diseases at Penn State. “This is important because the antibiotics that are commonly used to treat neonatal sepsis often won’t work for Paenibacillus infections.” The paper was published in the journal Clinical Infectious Disease.

Christine Hehnly, Ph.D., postdoctoral fellow and co-lead author of The Lancet Microbe paper, says, “For the first time, we were able to describe the progression of infections during the neonatal period to the development of infant post-infectious hydrocephalus, enabling us to guide the crucial diagnostics and interventions needed to prevent the devastating brain damage associated with post-infectious hydrocephalus.”

From discovery to treatment, the team was now certain that the Paenibacillus bacteria were to blame for the thousands of cases of postinfectious hydrocephalus that occur annually in Uganda. They also discovered that the pathogen thrives in moist environments, with the majority of cases occurring on the swampy shores of Lake Kyoga, where the Nile River originates, and Lake Victoria, where the Nile River originates. Cases also had a strong correlation with the rainy season, suggesting that the Paenibacillus came from the environment.

Schiff and colleagues are better able to predict whether newborn patients were likely infected with the Paenibacillus bacteria based on when and where they had been infected in order to circumvent the limitations that prevent doctors from using gene sequencing and PCR for diagnosis in settings with limited resources. Schiff’s team is collaborating with hospitals in Uganda to develop effective treatment plans for these patients.

Schiff is currently concentrating her fieldwork on locating the locations in rural environments where this bacterium lurks and comprehending the cultural newborn care practices that may contribute to high infection rates. The last thing we want to do is attempt to treat infants who have been infected with these highly virulent bacteria after learning everything we have. “We can develop public health policies that can prevent these infections if we can pinpoint how they are getting into infants,” Schiff stated.

Schiff and his coworkers have discovered the solution to one seemingly insurmountable issue, and they are now turning their technologies toward solving other issues. They are looking into the possibility of developing inexpensive sequencing systems at points of care to confirm infectious agents and tailor patient treatment. They are studying similar infections in Vietnam, Kenya, and the United States.

Schiff asserts, “This is why doctors conduct research.” We may be able to treat a large number of patients at once if we are extremely fortunate. I’m thrilled that, after all these years of research, we have discovered a new disease process and grateful to the medical professionals, scientists, and patients’ families for their collaborative efforts. “The universal currency that binds together so many people who have worked so hard together on this problem are newborn infants at risk of dying.”

More information: Sarah U Morton et al, Paenibacillus spp infection among infants with postinfectious hydrocephalus in Uganda: an observational case-control study, The Lancet Microbe (2023). DOI: 10.1016/S2666-5247(23)00106-4

Jessica E Ericson et al, Neonatal Paenibacilliosis: Paenibacillus infection as a Novel Cause of Sepsis in Term Neonates with High Risk of Sequelae in Uganda, Clinical Infectious Diseases (2023). DOI: 10.1093/cid/ciad337