Researchers have discovered a group of brain cells that could lead to a new approach to anti-obesity treatment. The hypothalamus is an important brain region involved in appetite regulation. Specific groups of neurons in the hypothalamus play critical roles in controlling hunger and satiety.

A group of brain cells discovered by the Garvan Institute of Medical Research boosts appetite when there is a prolonged surplus of energy in the body, such as excess fat accumulation in obesity. The researchers discovered that not only did these cells produce the appetite-stimulating molecule NPY, but they also made the brain more sensitive to the molecule, increasing appetite even more.

“When there is a surplus of energy in the body in the form of excess fat, these cells kickstart changes in the brain that make it more sensitive to even low levels of NPY – driving appetite during obesity,” explains Professor Herbert Herzog, senior author of the study and Visiting Scientist at Garvan. “Our study addresses a long-standing question about how appetite is controlled in obesity and has the potential to shift the development of therapy in a new direction.”

The findings were published in the journal Cell Metabolism.

Our brain has complex mechanisms that detect the amount of energy stored in our bodies and adjust our appetite accordingly. One way it does this is through the molecule NPY, which the brain naturally produces in response to stresses like hunger to stimulate eating.

Professor Herzog

The discovery of a vicious cycle

Obesity is a major public health issue and a disease that affects more than one in every ten adults and raises the risk of developing other chronic conditions such as diabetes or heart disease. While many factors can contribute to the development of obesity (an abnormal accumulation of fat tissue in the body), eating habits and physical activity levels are important.

“Our brain has complex mechanisms that detect the amount of energy stored in our bodies and adjust our appetite accordingly. One way it does this is through the molecule NPY, which the brain naturally produces in response to stresses like hunger to stimulate eating,” Professor Herzog explains.

“When the energy we consume falls short of the energy we spend, our brain produces higher levels of NPY. When our energy intake exceeds our expenditure, NPY levels drop and we feel less hungry. However, when there is a prolonged energy surplus, such as excess body fat in obesity, NPY continues to drive appetite even at low levels. We wanted to understand why.”

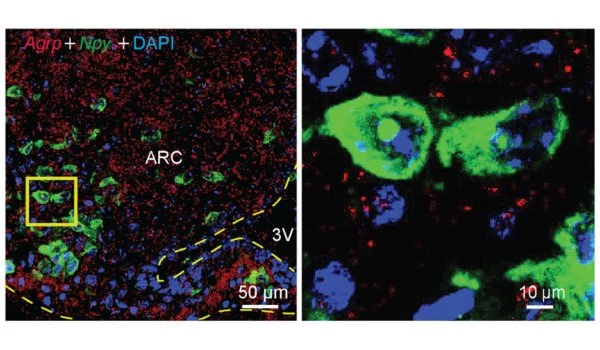

The researchers investigated neurons that produced NPY in mouse models of obesity and discovered that, surprisingly, 15% of them were different — they did not shut down NPY production during obesity.

“We discovered that under obese conditions, NPY produced by this subset of neurons was primarily responsible for appetite.” “Not only did these cells produce NPY, but they also sensitized other parts of the brain to produce additional receptors or ‘docking stations’ for the molecule, supercharging appetite even further,” Professor Herzog says.

“What we discovered is a vicious cycle that disrupts the body’s ability to balance energy input with energy storage and promotes the development of obesity.”

Wired to resist weight loss

“Our brain is wired to resist energy deficiency or weight loss because it perceives it as a threat to our survival and activates mechanisms that increase our appetite, causing us to seek food. We discovered that this happens even when we have excess energy stored in the body,” Professor Herzog explains.

According to the researchers, their discovery opens the door to blocking the additional, more sensitive NPY receptors as a novel approach to developing anti-obesity medication.

“Our discovery helps us better understand the mechanisms in the brain that interfere with balanced energy metabolism and how they may be targeted to improve health,” Professor Herzog says.