A team of researchers conducted a genetic study of the pathogen to better understand snake fungal disease (SFD). The goal was to determine whether SFD originated in the United States or was introduced from outside the country, which could provide a historical basis for how the disease emerged – and, ultimately, inform disease management.

Although it was only recently recognized as a problem in wildlife ecology, snake fungal disease (SFD) is a growing concern in the United States, with parallels to other well-known wildlife fungal diseases like white-nose syndrome in bats. SFD is lethal to snakes and, even in milder cases, impairs an animal’s ability to perform basic biological functions such as hibernation, eating, and avoiding predators.

To better understand SFD, a team of researchers led by Northern Arizona University’s Pathogen and Microbiome Institute’s assistant professor Jason Ladner conducted a genetic study of the pathogen, which was recently published in PLOS Biology as “The population genetics of the causative agent of snake fungal disease indicate recent introductions to the USA.”

Collaborating with study co-author Jeff Lorch of the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS) and other scientists from the USGS, Genencor Technology Center, the University of California-Riverside, Stetson University, the Institute of Zoology, the University of Kentucky and Holyoke Community College, Ladner’s goal was to determine whether SFD originated in the U.S. or was introduced from outside the country, which could provide a historical basis for how it emerged — and ultimately inform management of the disease.

The reason genomic data is useful for this is that when this fungus replicates, grows, and divides, the polymerase (the molecule that creates the new copy) occasionally makes mistakes. These errors result in mutations.

Jeff Lorch

“Snake fungal disease was first identified in the United States in 2008. There was a well-studied population of rattlesnakes in Illinois that developed some very serious fungal infections. ‘OK, what is this thing?’ people inquired. What is its location? What exactly is going on? Is this a novel emerging fungal pathogen?’ They eventually discovered that it was already almost everywhere, at least in the eastern half of the United States” Ladner stated.

SFD, though seemingly not as deadly as other wildlife fungal diseases, is still a worrying threat to animals that represent an important part of the ecosystem. “We’re very concerned, not just about SFD’s effect to drive population declines, but also as a contributing factor amongst many other threats that snakes are already facing, like habitat destruction or over-collection for the pet trade,” Lorch said.

Understanding wildlife diseases is critical, both for ecosystem health and for understanding their potential effects on humans. “I am particularly interested in wildlife diseases, in part because wildlife serve as important reservoirs for diseases that could potentially emerge in humans; SARS-coronavirus-2 is a prime example of this. If we are to be ready for the next emerging infectious disease in humans, we must first better understand the pathogens that are currently circulating in wildlife populations and may be transmitted to humans” Ladner stated.

However, the study presented some unique challenges. “There’s almost no long-term population trend data for snakes, especially when we compare snakes to bats, which have suffered from white-nose syndrome,” Lorch said. “Many states have historical data on bat populations because they are not as difficult to monitor as other types of wildlife. “

Snakes, on the other hand, “are very secretive creatures. Unless you’re looking for them, you’re unlikely to see them on the landscape on a regular basis “Lorch elaborates. Without a large body of historical data on snake populations in North America, “It’s difficult to say what snake populations were like before SFD was discovered. Long-term trends are extremely difficult to interpret.”

The team had two hypotheses about how the disease arrived in the United States before beginning research. According to one theory, the fungus that causes this disease was only recently introduced into the United States and has since spread over several decades, if not 100 years. The alternative hypothesis was that this pathogen has existed for a long time and is essentially native to the United States; perhaps it has existed for thousands of years and evolved alongside these snake populations. It may appear to be emerging in the latter case simply because we are looking for it right now.

Or there has been some type of environmental change, possibly related to climate change, that is leading to an increase in the number of cases despite the fact that this pathogen has always been present,” Ladner explained.

Ladner and Lorch created a “family tree” for strains of the fungus that causes SFD found in the United States in order to track the disease’s evolution. “Looking at the genetics of the pathogen to get an idea of how long it’s been here and how it’s changed over time was one of the ways we could reconstruct the history of the disease,” Lorch said.

The study of SFD genetics provided the team with a trail of breadcrumbs, revealing more about its history and shedding light on SFD cases in the United States. “The reason genomic data is useful for this is that when this fungus replicates, grows, and divides, the polymerase (the molecule that creates the new copy) occasionally makes mistakes. These errors result in mutations. The mutations will then be passed down through the generations. By examining the various mutations in the population, we can determine how long certain lineages have existed and how different strains are related to one another. And this can tell us a lot about how long SFD has been around” Ladner stated.

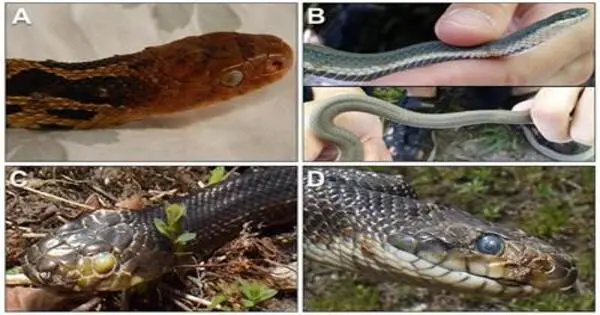

The team performed genetic sequencing on 82 strains of the fungus after collecting samples from various SFD-affected snakes. This included SFD strains isolated from wild snakes in the United States and Europe, as well as captive snakes from three continents. The team was able to partially reconstruct the evolutionary history of this fungus based on genetic similarities and differences between strains.

“In the U.S., we found that there are several divergent lineages of this fungus circulating, but a lack of intermediates between these lineages, which would be expected if they originated in the U.S. Because of that, we think that there were likely multiple, somewhat recent introductions of this fungus to the U.S., and that an unsampled population, somewhere else in the world, acted as a source,” Ladner said.

This evidence allowed the team to form conclusions on how SFD arrived in America. “It suggests that this fungus was introduced to the United States through anthropogenic means — humans moving these snakes around. The most likely culprit is the trading of captive snakes as pets: the different clonal lineages that we see in the U.S., we also see represented in captive snake populations,” Ladner said.

The study offers recommendations for future SFD management in the United States, as well as a better understanding of how it was introduced. “Imagine trying to stop the spread of the disease in the United States, and possibly even eradicating it, if we had caught SFD being introduced very early on.”

“Given how widespread it is, I believe that is unlikely at this point. However, I believe it is still important to better understand how SFD was introduced, as there is still the possibility of new introductions of diverse strains from these source populations. If we know that this fungus was introduced several times over the past several decades through the captive animal trade, then putting more restrictions and controls and testing animals in that process could be important for preventing further spread,” Ladner said.