Some types of brain cancer are less difficult to treat than others. A qualified neurosurgeon can carefully remove many solid tumors, such as diffuse midline gliomas, or DMGs, but others, such as DMGs, are far more difficult. Children with a DMG tumor are expected to live for fewer than a year.

In the future, a new study from the University of Pittsburgh School of Medicine could lead to a better, non-invasive technique to treat malignant cancers.

DMG cancers are unusually dependent on methionine, an amino acid that people must obtain from diet, according to a report published today in Nature Cancer by physician-scientists from Pitt and UPMC Children’s Hospital of Pittsburgh.

Drugs that target the methionine-processing machinery in malignant cells in the brain but not the rest of the body could pave the path for new non-invasive therapies.

“The Achilles’s heel of these tumors is that they are rapidly growing and use a lot of nutrients,” said Sameer Agnihotri, Ph.D., assistant professor of neurological surgery at Pitt.

“Combining metabolic approaches changes in diet with next-generation scientific tools might become a way of harnessing our understanding of how nutrient needs of cancer cells differ from normal cells and lead to more effective personalized cancer therapies in the future.”

Only leukemia outnumbers brain cancer as the most frequent type of cancer in youngsters. However, unlike leukemia, which has a very high survival rate because to medical advances over the last century, brain cancer is the leading cause of cancer death in children. DMGs are the most lethal of all brain malignancies.

Everyone in the field of brain cancer, scientists and neurosurgeons alike, are often asked if there is a diet change that a patient can take to aid their recovery. Small steps like these give patients and their families a sense of control and optimism.

Sameer Agnihotri

The midbrain, which is frequently affected by DMG tumors, is a vital link between the brain cortex and the spinal cord. It is important for complicated information processing, logical reasoning, and thinking.

Because those tumors are buried deep within the brain, surgery is often impossible, and radiation therapy is often ineffective.

“None of the standard chemotherapy approaches that have been successfully tested in adults were a home run in children with this type of cancer,” said Agnihotri.

“Pediatric cancers are so distinct and different from adults. In young children, brain tumors grow just as the brain is trying to develop normally, so anticancer therapies can have many side effects.”

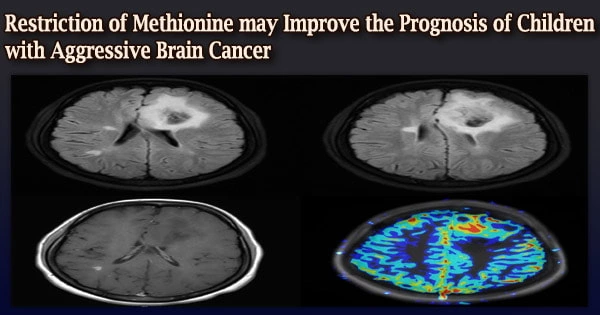

DMG cells, on the other hand, may have a unique vulnerability that could be exploited for therapeutic purposes. A close examination of the genetic code of those cells revealed that they have a distinctive feature: a mutation in proteins that provide structural support to the DNA, making them especially vulnerable to methionine deficiency.

Methionine is one of nine “essential” amino acids, or building blocks, that our bodies need to produce proteins. Because the human body lacks the technology to produce methionine from scratch, the only method to replenish its stocks is to eat methionine-rich foods like poultry and legumes.

Researchers put cancer cells in a Petri dish and observed their behavior while decreasing one nutrient at a time to see if changing their diet may reduce the growth of DMG tumors. When scientists removed methionine from the cells, it was obvious that the cancer cells’ development was significantly slowed.

Researchers also discovered that inhibiting cancer cell development and increasing survival in mice with aggressive DMG tumors by eliminating a crucial enzyme involved in processing methionine into other components essential for many biological activities.

In a separate study, sick mice were given a methionine-restricted diet and their life expectancy increased by nearly half. The team is currently working on a proposal for a clinical study to evaluate medications that target methionine metabolism in humans. They believe that the trial will be launched in the near future.

“Everyone in the field of brain cancer, scientists and neurosurgeons alike, are often asked if there is a diet change that a patient can take to aid their recovery. Small steps like these give patients and their families a sense of control and optimism,” said Agnihotri.

“The answer to that question is complicated. A diet change alone probably won’t have a dramatic effect, but maybe it can complement other therapies and make them more effective.”