New exploration has uncovered that the most common way of “peopling” the whole landmass of Sahul—tthe consolidated uber-continent that got Australia together with New Guinea when ocean levels were a lot lower than today—took 10,000 years.

New, modern models joined late upgrades in demography and models of wayfinding in view of geographic deduction to show the size of the difficulties faced by the precursors of Native individuals making their mass movement across the supercontinent a long time ago.

Native peoples most likely first entered the landmass quite some time ago on what is now the island of Timor, followed by later movements through western New Guinea.

As per the new exploration, this example prompted a fast extension both toward the south toward the incomparable Australian Bight and toward the north from the Kimberley locale to settle all pieces of New Guinea and, later, the southwest and southeast of Australia.

“Because our model integrates local circumstances, such as the spatial and temporal patterns of the land’s ability to offer food, the distribution of water sources, and terrain, our migration patterns would be extremely applicable when applied to other parts of the world.”

Dr. Stefani Crabtree, co-author of the study.

The exploration was driven by the Bend Focus of Greatness for Australian Biodiversity and Legacy (CABAH) and saw global specialists in Australia and the US team up to examine the most probable pathways and the time span expected to arrive at population sizes ready to endure the afflictions of their new climate.

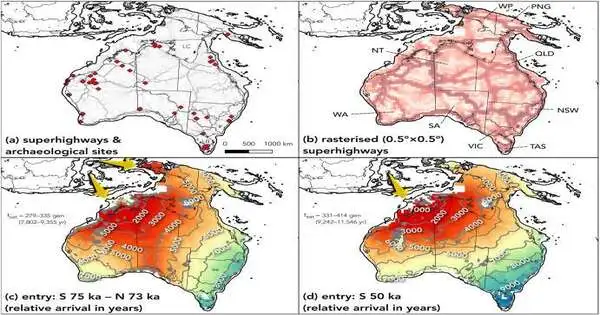

By joining two existing models and anticipating the courses they took—”expressways”—and the segment design of these first populations, the analysts had the option to exactly gauge the ideal opportunity for mainland immersion. The new exploration has recently been distributed in the Quaternary Science Audits diary.

In view of definite recreations of the geology of the old mainland and models of past environments, the scientists fostered a virtual landmass and modified populations to get by in and move effectively through their new area.

Exploring by following scene highlights like mountains and slopes and knowing where to find water prompted fruitful route systems. The main people of Australia quickly passed down social information to succeeding generations, working with the population of the entire landmass.

However, the difficulties set forth by the geology of Sahul prompted a slower speed of movement. Past models didn’t consider the geological imperatives that this modern model does, considering a more sensible assessment of the peopling of the mainland. This new work also makes sense of the slower progress Native forefathers made in reaching Tasmania, which was possibly made possible when seawaters across Bass Straight subsided—as only possible by combining these model outcomes.

According to the review’s lead author, Corey Bradshaw, and Matthew Flinders, Professor of Global Nature at Flinders University and CABAH Models Topic Pioneer, these joined models consider a superior comprehension of the archeological and hereditary data, making sense of the extraordinary movements of Native people in Sahul.

“The manners in which that individual connects with landscape, nature, and possibly others modify our model results, giving more sensible outcomes.” Hence, models that integrate just segment data, disregarding the assets and necessities of voyagers as well as the open doors and limitations to their movement, are probably going to misjudge the planning of ventures into new locales. Thus, we currently have a decent forecast of the examples and cycles of how individuals initially settled these grounds a huge number of years prior.

“Our refreshed display shows that New Guinea was populated slowly north of 5000 to 6000 years ago, with an emphasis at first on the focal high countries and Arafura Ocean region prior to arriving at the Bismarck Archipelago in the east.” “The peopling of the far southeast and Tasmania is estimated to have occurred between 9000 and 10,000 years after the first appearance in Sahul.”

Teacher Bradshaw says the creative model created by the analysts could be changed for different areas of the planet to examine the timing and examples of starting populations by people.

“Analyzing similar examples in Center East locales as people left North-eastern Africa, passed through and spread into Europe, extended across southern Asia, and developed from Gold Country to South America is now possible using a similar display approach.”

“Since our model integrates nearby circumstances, including the spatial and fleeting examples of the land’s capacity to give food, the dispersion of water sources, and geology, our movement examples would be profoundly important when applied to different areas of the planet.”

“These outcomes are amazing and extremely convincing,” says Dr. Stefani Crabtree, co-creator of the review, individual at the St. Nick Fe Foundation, and assistant teacher at Utah State College.

“Our work shows that we want to remember the limitations put on voyagers by basic geology as well as logical segment situations.” Also, as this work depends on how we might interpret human development worldwide, it can have huge ramifications for grasping movement in different spots at different times. This likewise goes to show the force of joining computational models with paleohistory and the humanities for refining how we might interpret mankind.

“This kind of work is a unique advantage.”

More information: Corey J.A. Bradshaw et al, Directionally supervised cellular automaton for the initial peopling of sahul, Quaternary Science Reviews (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.quascirev.2023.107971

Journal information: Quaternary Science Reviews