What’s the significance of being human here?

From here onward, for quite a while, the response appeared to be clear. Our species, Homo sapiens, with our perplexing contemplations and profound feelings, were the main genuine people to at any point walk the Earth. Prior structures, similar to the Neanderthals, were believed to be simply ventures along the way of advancement, who vanished on the grounds that we were better variants.

That image is currently evolving.

As of late, analysts have acquired the ability to pull DNA from antiquated hominins, including our initial predecessors and different family members who strolled on two legs. Old DNA innovation has changed the manner in which we concentrate on mankind’s set of experiences and has in practically no time taken off, with a consistent stream of studies investigating the qualities of quite a while in the past individuals.

Alongside additional fossils and relics, the DNA discoveries are guiding us toward a difficult thought: We’re not all that unique. For a large portion of mankind’s set of experiences, we imparted the planet to different sorts of early people, and those now-terminated bunches were a great deal like us.

“We can see them as completely human. However, an interesting type of human, Another way to be human.”

Chris Stringer, a human evolution expert at London’s Natural History Museum.

“We can consider them to be completely human. Yet, curiously, an alternate sort of human,” said Chris Stringer, a human development master at London’s Regular History Historical Center. “An alternate method for being human.”

In addition, people had close—even cozy—communications with a portion of these different gatherings, including Neanderthals, Denisovans, and “phantom populaces,” as we just know from DNA.

“It’s an exceptional time in mankind’s set of experiences when there is only one of us,” Stringer said.

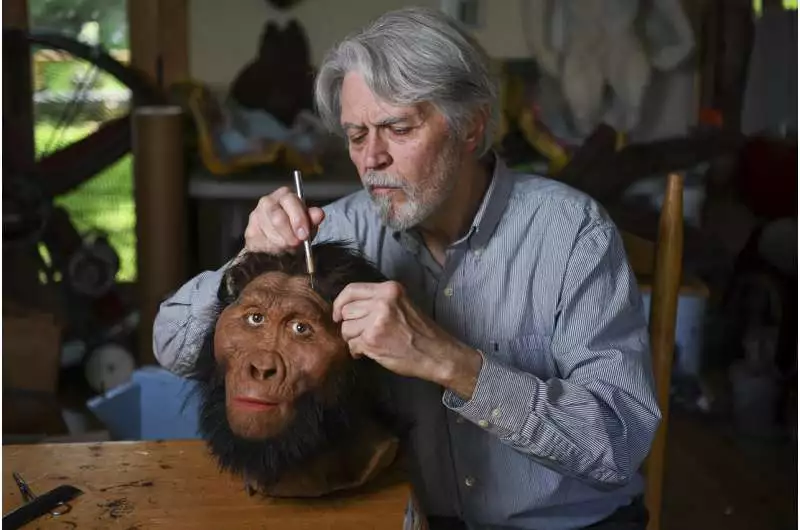

Paleoartist John Gurche inserts hair on Shanidar 1, a male Neanderthal, at his studio in Trumansburg, N.Y., on Wednesday, May 31, 2023. In 2010, the Swedish geneticist Svante Paabo and his group sorted out a precarious riddle. They had the option to collect pieces of old DNA into a full Neanderthal genome—an accomplishment that was, for quite some time, remembered to be incomprehensible. Credit: AP Photograph/Heather Ainsworth

A WORLD WITH MANY HOMININS

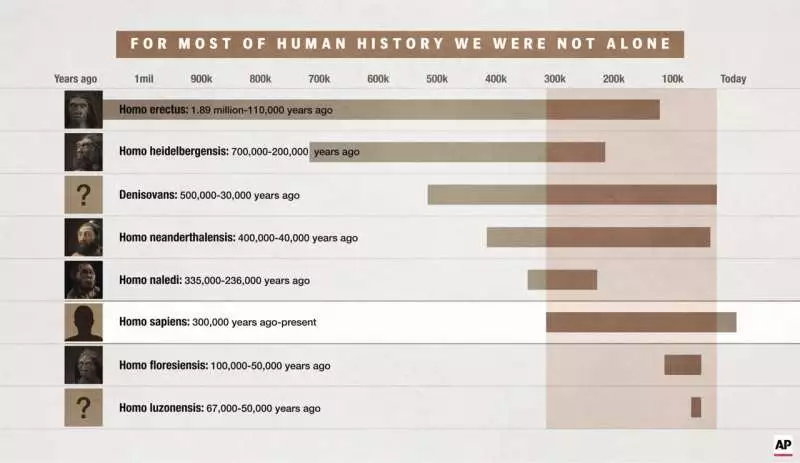

Researchers presently know that after H. sapiens first appeared in Africa, something like a long time ago, they were covered with an entire cast of other hominins, according to Rick Potts, head of the Smithsonian’s Human Starting Points Program.

Neanderthals were hanging out in Europe. Homo heidelbergensis and Homo naledi were living in Africa. The short-statured Homo floresiensis, sometimes known as the “Hobbit,” was living in Indonesia, while the long-legged Homo erectus was loping around Asia.

Researchers began to understand that every one of these hominins wasn’t our immediate progenitors. All things being equal, they were more similar to our cousins: genealogies that split off from a typical source and veered off.

Archeological finds have shown some of them had complex ways of behaving. Neanderthals painted cave walls, Homo heidelbergensis chased huge creatures like rhinos and hippos, and a few researchers think even the little-brain Homo naledi was covering its dead in South African cavern frameworks. A study last week found early people were building structures with wood before H. sapiens advanced.

Scientists additionally pondered: On the off chance that these different sorts of people were not really unique, did our predecessors have intercourse with them?

As far as some might be concerned, the blending was difficult to envision. Many contended that as H. sapiens branched out of Africa, they supplanted different gatherings without mating. Classicist John Shea of New York’s Stony Stream College said he used to consider Neanderthals and H. sapiens as opponents, accepting that “in the event that they caught one another, they’d presumably kill one another.”

Paleoartist John Gurche embeds individual strands of hair on a male Paranthropus robustus model at his studio in Trumansburg, N.Y., on Wednesday, May 31, 2023. “These were once authentic people. Furthermore, they felt despondency, delight, and torment,” Gurche said. “They’re not in some fairyland; they’re not some dream animals. They were alive.” Credit: AP Photograph/Heather Ainsworth

DNA Uncovers Old Mysteries

In any case, DNA has uncovered that there were different cooperation’s—ones that changed who we are today.

In 2010, the Swedish geneticist Svante Paabo and his group sorted out a precarious riddle. They had the option to gather sections of old DNA into a full Neanderthal genome, an accomplishment that was for quite some time remembered to be unthinkable and won Paabo a Nobel Prize a year ago.

This capacity to peruse old DNA altered the field, and it is continually moving along.

For instance, when researchers applied these methods to a pinky bone and a few gigantic molars found in a Siberian cavern, they found qualities that matched nothing seen previously, said Bence Viola, an anthropologist at the College of Toronto who was important for the exploration group that made the revelation. It was another type of hominin, presently known as Denisovans, who were the principal human cousins, distinguished simply by their DNA.

Equipped with these Neanderthal and Denisovan genomes, researchers could contrast them with individuals today and search for lumps of DNA that match. At the point when they did, they tracked down obvious indicators of hybrid

Paleoartist John Gurche chips away at the remaking of Lucy, an Australopithecus afarensis female hominin, at his studio in Trumansburg, N.Y., on Wednesday, May 31, 2023. Credit: AP Photograph/Heather Ainsworth

THE NEW HUMAN STORY

The DNA proof showed that H. sapiens mated with bunches, including Neanderthals and Denisovans. It even uncovered proof of other “phantom populaces”—bunches” that are important for our hereditary code but whose fossils we haven’t found at this point.

It’s difficult to nail down precisely when and where these collaborations occurred. Our precursors appear to have blended in with the Neanderthals not long after leaving Africa and heading into Europe. They most likely caught the Denisovans in pieces of East and Southeast Asia.

“They didn’t have a guide; they didn’t have the foggiest idea where they were going,” the Smithsonian’s Potts said. “In any case, investigating the following slope into the following valley, they ran into populations of individuals that appeared to be a piece unique to themselves, however mated, traded qualities.”

So despite the fact that Neanderthals looked unmistakable from H. sapiens—from their greater noses to their more limited appendages—it wasn’t sufficient to make a “wall” between the gatherings, Shea said.

“They most likely thought, ‘Gracious, these folks look somewhat changed,'” Shea said. “‘Their skin variety’s somewhat unique. Their countenances look somewhat changed. Yet, they’re cool folks; how about we go attempt to converse with them?'”

Paleoartist John Gurche models for a representation holding a reproduced male Paranthropus robustus model at his studio in Trumansburg, N.Y., on Wednesday, May 31, 2023. “My most memorable love was generally human development,” said Gurche, who makes forensically precise and practical portrayals of Neanderthals and hominins. Credit: AP Photograph/Heather Ainsworth

COMPLEX NEANDERTHALS

The possibility that cutting-edge people, and especially white people, were the zenith of development came from a period of “imperialism and elitism,” said Janet Youthful, caretaker of actual human sciences at the Canadian Gallery of History.

One Neanderthal composition, made to mirror the vision of a selective breeding supporter, cleared its path through many years of reading material and exhibition hall shows.

The new discoveries have totally overturned the possibility that, before, more primate-like animals stood up straighter and got more complicated until they arrived at their pinnacle structure in H. sapiens, Youthful said. Alongside the hereditary proof, other archeological finds have shown Neanderthals had complex ways of behaving around hunting, cooking, utilizing devices, and, in any event, making craftsmanship.

In any case, despite the fact that we currently realize our old human cousins were like us—and make up a piece of who we are presently—gorilla-like cave dwellers have been difficult to unstick.

Craftsman John Gurche is attempting He works on making exact models of antiquated people for galleries, including the Smithsonian and the American Exhibition Hall of Normal History, in order to assist public discernment with getting up to speed with the science.

Skulls and figures looked out from the racks of his studio recently as he dealt with a Neanderthal head, punching bits of hair into the silicone skin.

For quite a bit of history, Homo sapiens lived close by different sorts of old people and, surprisingly, mated with some of them. Credit: AP Advanced Insert

Carrying the new view to people in general hasn’t been simple. Gurche said, “This mountain man picture is exceptionally constant.”

For Gurche, getting the science right is essential. He has chipped away at analyses of people and gorillas to figure out their life systems, yet in addition, he desires to acquire them out of feeling his depictions.

“These were once absolutely real people. What’s more, they felt misery, satisfaction, and torment,” Gurche said. “They’re not in some fairyland; they’re not some dream animals. They were alive.”

Numerous associations are still to be found.

Researchers can’t get helpful hereditary data out of each and every fossil they find, particularly assuming it’s truly old or in some unacceptable environment. They haven’t had the option to accumulate a lot of old DNA from Africa, where H. sapiens first advanced, on the grounds that it has been corrupted by intensity and dampness.

In any case, many are confident that as DNA innovation continues to propel, we’ll have the option to drive further into the past and get old genomes from additional regions of the planet, adding more brushstrokes to our image of mankind’s set of experiences.

Since, despite the fact that we were the only ones to make due, the other terminated bunches assumed a vital part in our set of experiences and our present. They are essential for a typical man to interact with each individual, said Mary Prendergast, a Rice College paleontologist.

“Assuming you take a gander at the fossil record, the archeological record, and the hereditary record,” she said, “you see that we share undeniably more in like manner than which isolates us.”