Researchers have developed plants in soil from the Moon, a first in mankind’s set of experiences and an achievement in lunar and space investigation.

In another paper distributed in the journal Communications Biology, University of Florida specialists demonstrated the way that plants can effectively grow and fill in lunar soil. Their study also examined how plants respond naturally to the Moon’s dirt, otherwise called lunar regolith, which is drastically not quite the same as soil found on Earth.

This work is an initial move toward one day developing plants for food and oxygen on the Moon or during space missions. All the more right away, this examination comes as the Artemis Program intends to return people to the Moon.

“Artemis will require a better understanding of how to grow plants in space,”

Rob Ferl professor of horticultural sciences in the UF Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS)

“Artemis will require a superior understanding of how to develop plants in space,” said Rob Ferl, one of the review’s creators and a recognized teacher of green sciences in the UF Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences (UF/IFAS).

Indeed, even at the beginning of lunar investigation, plants assumed a significant part, said Anna-Lisa Paul, one of the review’s creators and an exploration teacher of agricultural sciences at UF/IFAS.

“Plants laid out that the dirt examples brought back from the moon didn’t hold onto microbes or other obscure parts that would hurt earthbound life, but those plants were just tidied with the lunar regolith and were never really filled in,” Paul said.

Anna-Lisa Paul takes a stab at dampening the lunar soil with a pipette. The researchers found that the dirt repulsed water (was hydrophobic), making the water globule up on a superficial level. Dynamic blending of the material with water was expected to break the hydrophobicity and consistently wet the dirt. When soaked, the lunar soil could be wetted by fine activity for plant culture. Tyler Jones, University of Florida/IFAS

Paul and Ferl are globally recognized specialists in the investigation of plants in space. Through the UF Space Plants Lab, they have sent probes on space transports to the International Space Station and on suborbital flights.

“For future, longer space missions, we might involve the Moon as a center point or takeoff platform. “It’s a good idea that we would need to utilize the dirt that is now there to develop plants,” Ferl said. “All in all, what happens when you develop plants in lunar soil, something absolutely beyond a plant’s developmental encounter? What might plants do in a lunar nursery? “Might we at some point have lunar ranchers?”

Ferl and Paul devised a deceptively simple experiment to begin answering these questions: sow seeds in lunar soil, add water, supplements, and light, and record the results.

The difficulty: The researchers just had 12 grams—only a couple of teaspoons—of lunar soil with which to do this trial. Borrowed from NASA, this dirt was gathered during the Apollo 11, 12, and 17 missions to the Moon. Paul and Ferl applied multiple times throughout 11 years for an opportunity to work with the lunar regolith.

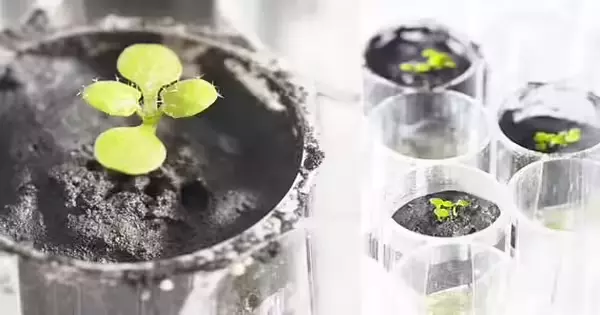

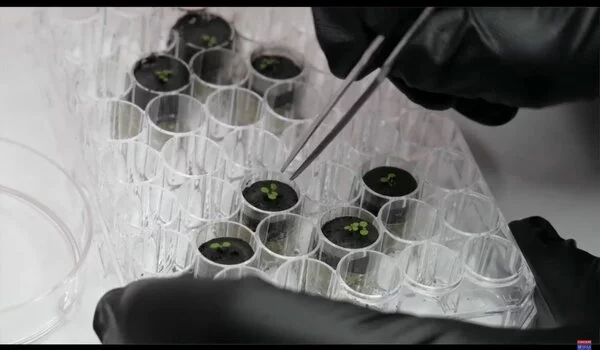

The modest quantity of soil, also its limitless authentic and logical importance, implied that Paul and Ferl needed to plan a limited-scale, painstakingly arranged exploration. To develop their minuscule lunar nursery, the specialists utilized thimble-sized wells in plastic plates typically used to culture cells. They all very much worked as pots. When they filled each “pot” with roughly a gram of lunar soil, the researchers dampened the dirt with a supplement arrangement and added a couple of seeds from the Arabidopsis plant.

Arabidopsis is generally used in plant sciences on the grounds that its hereditary code has been completely planned. Developing Arabidopsis in the lunar soil permitted the specialists more insight into what the dirt meant for the plants, down to the degree of quality articulation.

Burglarize Ferl, left, and Anna-Lisa Paul examine the plates filled with lunar soil and control soil, which are currently under LED developing lights.At that point, the researchers couldn’t say whether the seeds would try and develop in the lunar soil. Tyler Jones, University of Florida/IFAS

As a point of comparison, the scientists also discovered Arabidopsis in JSC-1A, an earthbound substance that resembles genuine lunar soil as well as Martian soils and earthly soils from extreme conditions.The plants that filled in these non-lunar soils were the examination’s benchmark group.

Before the examination, the analysts didn’t know whether the seeds planted in the lunar soil would grow. Yet, essentially every one of them did.

“We were stunned. “We didn’t foresee that,” Paul said. “That let us know that the lunar soils didn’t interfere with the chemicals and signs engaged with plant germination.”

As time went on, the scientists noticed contrasts between the plants that filled in the lunar soil and the benchmark group. For instance, a portion of the plants that filled in the lunar soils were more modest, developed all the more leisurely or were more shifted in size than their partners.

These were all actual signs that the plants were attempting to adapt to the substance and primary make-up of the moon’s dirt, which Paul made sense of. This was additionally affirmed when the specialists dissected the plants’ quality articulation designs.

“At the hereditary level, the plants were taking out the apparatuses normally used to adapt to stressors like salt and metals or oxidative pressure, so we can gather that the plants see the lunar soil climate as upsetting,” Paul said. “At last, we might want to utilize the quality articulation information to assist with addressing how we can improve the pressure reactions to the level where plants — especially crops — can fill in lunar soil with almost no effect on their wellbeing.”

Anna-Lisa Paul, left, and Rob Ferl, working with lunar soils in their lab. Tyler Jones, University of Florida/IFAS

How plants respond to lunar soil might be connected to where the dirt was gathered, said Ferl and Paul, who teamed up on the review with Stephen Elardo, an associate professor of topography at UF.

For example, the analysts observed that the plants with the most indications of stress were those filled in what lunar geologists call “mature lunar soil.” These experienced soils are those presented to more enormous breezes, which adjust their cosmetics. Then again, plants that filled in similarly less experienced soils fared better.

Developing plants in lunar soils may likewise change the actual dirt, Elardo said.

“The Moon is an incredibly dry spot. How might minerals in the lunar soil respond to having a plant developed in them, with the additional water and supplements? Will adding water make the mineralogy more affable to plants? ” Elardo said.

Follow-up examinations will expand on these inquiries. From there, the sky is the limit. Until further notice, the researchers are celebrating having moved toward developing plants on the Moon.

“We needed to do this examination in light of the fact that, for a really long time, we were posing this inquiry: Would plants fill in lunar soil?” Ferl said. “The response, it ends up, is yes.”