The beginning of Mercury, the nearest planet to the sun, is strange in numerous ways. It has a metallic center, similar to Earth, yet its center makes up a much bigger part of its volume—85%, compared with 15% for Earth.

The NASA Disclosure Class Courier (Mercury Surface, Space Climate, Geochemistry, and Running) mission and the first shuttle to circle Mercury caught estimations uncovering that the planet likewise unequivocally varies synthetically from Earth. Mercury was formed from various building blocks in the early solar system because it has relatively less oxygen. Be that as it may, it has proven challenging to exactly nail down Mercury’s oxidation state from accessible information.

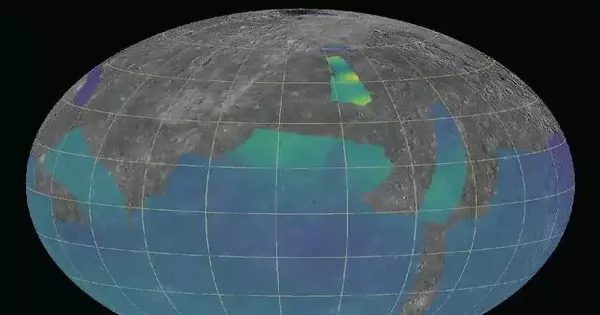

In another review driven by Arizona State College researcher Larry Nittler of the School of Earth and Space Investigation, information gained during the Courier mission was utilized to quantify and plan the wealth of the minor component chromium across Mercury’s surface.

“This is the first time chromium has been directly detected and mapped across any planetary surface. Depending on the amount of accessible oxygen, mercury prefers to reside in oxide, sulfide, or metal minerals, and by combining the data with cutting-edge modeling, we can gain unique insights on Mercury’s genesis and geological history.”

Arizona State University scientist Larry Nittler, of the School of Earth and Space Exploration,

Chromium is regularly known for being incredibly gleaming and impervious to consumption on metal work, and it gives tone to rubies and emeralds. Be that as it may, it likewise can exist in a great many compound states, so its overflow can give data about the synthetic circumstances under which it was integrated into rocks.

Nittler and partners found that the amount of chromium changes across Mercury by an element of around four. They determined hypothetical models of how much chromium would be supposed to be available at Mercury’s surface as the planet is isolated into a hull, mantle, and center under shifting circumstances. The researchers were able to set new limits on Mercury’s overall oxidation state by comparing these models to the measured chromium abundance. They discovered that Mercury must have chromium in its large metallic core.

The work is published in the Journal of Geophysical Research in July: Planets.

According to Nittler, “chromium has been directly detected and mapped across any planetary surface for the first time.” Mercury prefers to be in oxide, sulfide, or metal minerals, depending on the amount of oxygen available. By combining the data with cutting-edge modeling, we can gain unique insights into Mercury’s origin and geological history.”

The modeling described in the paper was carried out by Western Washington University co-author Asmaa Boujibar, who added: Our model, in light of lab tests, affirms that most of the chromium in Mercury is concentrated inside its center. We are unable to directly compare Mercury’s surface composition with data from terrestrial rocks because of its unique composition and formation conditions. As a result, it is absolutely necessary to carry out experiments that replicate the particular oxygen-deficient environment that the planet was formed in, which is distinct from either Mars or Earth.”

In the study, Nittler, Boujibar, and their co-authors analyzed the behavior of chromium under varying oxygen abundances in the system and compiled data from laboratory experiments. After that, they came up with a model to see how chromium was distributed among Mercury’s layers.

Similar to iron, the findings show that chromium is indeed sequestered in the core in large quantities. The scientists likewise saw that as the planet turns out to be progressively oxygen-lacking, a bigger measure of chromium is hidden inside. This information altogether upgrades how we might interpret the basic organization and land processes at play inside Mercury.

More information: Larry R. Nittler et al, Chromium on Mercury: New Results From the MESSENGER X‐Ray Spectrometer and Implications for the Innermost Planet’s Geochemical Evolution, Journal of Geophysical Research: Planets (2023). DOI: 10.1029/2022JE007691