Since basically the hours of inquisitive personalities like Plato, savants and researchers have pondered the inquiry, “What’s so amusing?” The Greeks credited the wellspring of humor to feelings prevalent to the detriment of others. The German psychoanalyst Sigmund Freud accepted that humor was a method for delivering repressed energy. U.S. comic Robin Williams tapped his outrage at the silly to make individuals giggle.

It appears to be nobody can truly settle on the subject of “What’s so interesting?” Consider attempting to teach a robot to laugh.Yet, that is precisely the exact thing a group of scientists at Kyoto College in Japan are attempting to do by planning a man-made intelligence that takes its signs through a common giggling framework. The researchers depict their creative way of dealing with building an entertaining bone for the Japanese android “Erica” in the most recent issue of the journal Boondocks in mechanical technology and man-made intelligence.

Maybe robots can’t identify giggling or even emit a laugh at a terrible father joke. Rather, the test is to make the human subtleties of humor for a man-made intelligence framework to work on normal discussions among robots and individuals.

“We believe that empathy is a key component of conversational AI. Of course, conversation is more than merely answering right. So we realized that one way a robot may sympathize with users is to share their laughing, something a text-based chatbot cannot do.”

Dr. Koji Inoue, an assistant professor at Kyoto University

“We feel that one of the significant elements of conversational man-made intelligence is sympathy,” made sense of lead creator Dr. Koji Inoue, an associate teacher at Kyoto College in the Branch of Knowledge Science and Innovation inside the Master’s level college of Informatics. “Discussion is, obviously, multimodal, not simply answering accurately. So we concluded that one way a robot can feel for clients is to share their giggling, which you can’t do with a text-based chatbot. “

Something interesting occurred.

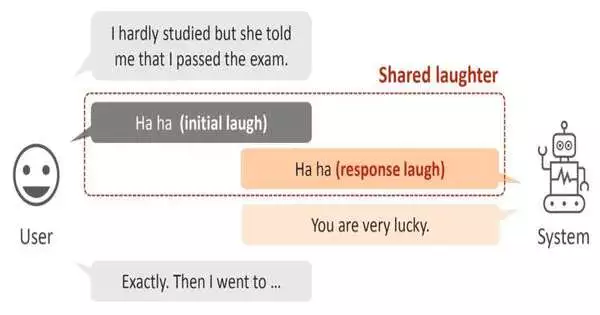

In the common giggling model, a human at first snickers, and the man-made intelligence framework answers with chuckling as a sympathetic reaction. This approach required planning three subsystems—one to identify giggling, one moment to choose whether to snicker, and a third to choose the kind of proper chuckling.

The researchers assembled preparing information by explaining in excess of 80 exchanges from speed dating, a social situation where huge gatherings blend or connect with one another one-on-one for a short timeframe. For this situation, the matchmaking long distance race included understudies from Kyoto College and Erica, teleoperated by a few novice entertainers.

“Our greatest test in this work was recognizing the genuine instances of shared giggling, which is difficult, on the grounds that, as you are probably aware, most chuckling is really not shared by any means,” Inoue said. “We needed to painstakingly sort precisely which giggles we could use for our examination and not simply expect that any snicker could be answered.”

The sort of giggling is likewise significant, on the grounds that, at times, a pleasant laugh might be more appropriate than a noisy grunt of chuckling. The trial was restricted to social versus happy giggles.

The robot gets it.

The group at last tried Erica’s new funny bone by making four short, brief exchanges between an individual and Erica with her new common giggling framework. In the main situation, she just expressed social giggling, followed simply by merry snickers in the second and third trades, with the two kinds of chuckling joined in the last exchange. The group made two different arrangements of comparable exchanges as gauge models. In the first, Erica won’t ever giggle. In the second, Erica expresses a social giggle each time she recognizes a human chuckle without utilizing the other two subsystems to channel the unique situation and reaction.

The analysts publicly supported in excess of 130 individuals altogether to pay attention to every situation inside the three unique circumstances—shared-giggling framework, no chuckling, all giggling—and assessed the connections in terms of sympathy, effortlessness, human-similarity, and understanding. The common giggling framework performed better compared to one or the other gauge.

“The main effect of this paper is that we have demonstrated the way that we can join each of the three of these errands into one robot. “We accept that this kind of joined framework is vital for legitimate giggling conduct, not just recognizing a chuckle and answering it,” Inoue said.

Like lifelong companions,

There are still a lot of other giggling styles to show and prepare Erica for before she is prepared to raise a ruckus around town on the circuit. “There are numerous other giggling capabilities and types that should be thought of, and this isn’t a simple errand. We haven’t even endeavored to show unshared giggles despite the fact that they are the most widely recognized, “Inoue noted.

Obviously, giggling is only one part of having a characteristic human-like discussion with a robot.

“Robots ought to really have a particular person, and we feel that they can show this through their conversational ways of behaving, for example, giggling, eye staring, motions, and talking style,” Inoue added. “We don’t think this is a simple issue by any means, and it might well take beyond 10 to 20 years before we can at last have a relaxed talk with a robot like we would with a companion.”

More information: Can a robot laugh with you?: Shared laughter generation for empathetic spoken dialogue, Frontiers in Robotics and AI (2022). DOI: 10.3389/frobt.2022.933261