When a person gets a cut, scrape, burn, or other wound, the body tends to it on its own and heals itself. However, this is rarely the case. Diabetes has the potential to impede the healing process, resulting in persistent wounds that are susceptible to infection and spreading.

Chronic wounds of this kind don’t just make people who have them disabled. Additionally, they put a strain on healthcare systems, costing the United States alone $25 billion annually.

Another sort of brilliant swath created at Caltech might make treatment of these injuries simpler, more compelling, and more affordable. Wei Gao, assistant professor of medical engineering, Heritage Medical Research Institute investigator, and Ronald and JoAnne Willens Scholar, developed these smart bandages in his laboratory.

“A stretchable wireless wearable bioelectronic system for multiplexed monitoring and combination treatment of infected chronic wounds” is the title of the research paper that was published in the March 24 issue of Science Advances.

“There are many different types of chronic wounds, including diabetic ulcers and burns that endure a long period and cause significant problems for the patient. There is a need for technologies that can help in recuperation.”

Wei Gao, assistant professor of medical engineering, Heritage Medical Research Institute Investigator.

“There are a wide range of kinds of ongoing injuries, particularly in diabetic ulcers and complications, that keep going quite a while and cause immense issues for the patient,” Gao says. “Recovery-facilitating technology is in high demand.

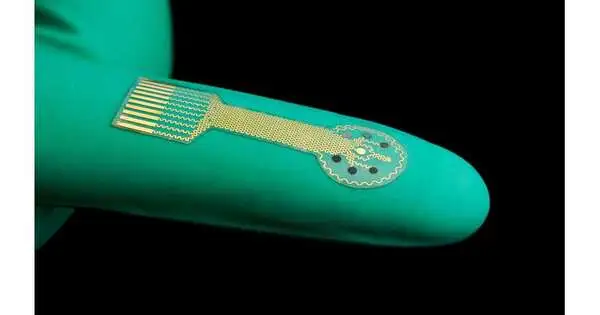

The smart bandages, in contrast to conventional bandages, which may only consist of layers of absorbent material, are constructed from a stretchy, flexible polymer with embedded electronics and medication. The electronics of the sensor let it look for molecules like uric acid or lactate as well as conditions like the wound’s pH level or temperature that could indicate bacterial infection or inflammation.

Wei Gao’s shrewd wraps are adaptable, permitting them to remain on the skin even as it stretches and moves.

There are three ways the bandage can react: To begin, it can wirelessly transfer the collected data from the wound to a nearby computer, tablet, or smartphone for the patient or a medical professional to review. Second, it is able to deliver an antibiotic or another medication that is contained within the bandage directly to the site of the wound to treat the infection and inflammation there. Thirdly, it is able to apply a low-level electrical field to the wound to encourage the growth of new tissue and speed up the healing process.

The smart bandages demonstrated their ability to speed up the healing of chronically infected wounds, similar to those found in humans, as well as to provide researchers with real-time updates about the animal’s metabolic states in laboratory animal models.

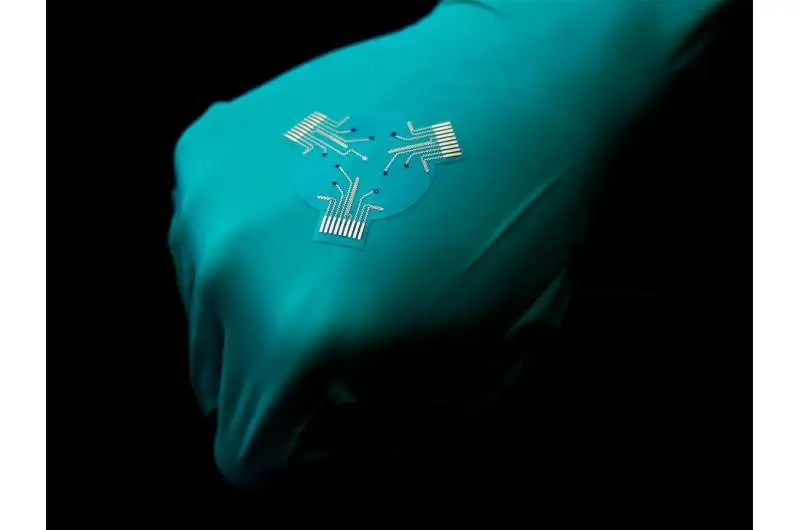

On the back of a gloved hand is a larger version of the smart bandage.

The findings, according to Caltech Gao, are encouraging, and he goes on to say that future research with the Keck School of Medicine at USC will focus on improving the bandage technology and testing it on human patients, who may have different therapeutic requirements than lab animals.

He states, “We have shown this proof of concept in small animal models, but down the road, we would like to increase the stability of the device and also test it on larger chronic wounds because the wound parameters and microenvironment may vary from site to site.” Additionally, he adds, “We have shown this proof of concept in small animal models.”

More information: Ehsan Shirzaei Sani et al, A stretchable wireless wearable bioelectronic system for multiplexed monitoring and combination treatment of infected chronic wounds, Science Advances (2023). DOI: 10.1126/sciadv.adf7388. www.science.org/doi/10.1126/sciadv.adf7388