Jigang Wang gave a brief overview of a novel kind of microscope that could aid in the understanding and eventual development of the underlying workings of quantum computing.

Wang, a professor of physics and astronomy at Iowa State University and a member of the Ames National Laboratory of the U.S. Department of Energy, explained how the instrument operates at extreme scales of space, time, and energy, including billionths of a meter, quadrillionths of a second, and trillions of electromagnetic waves per second.

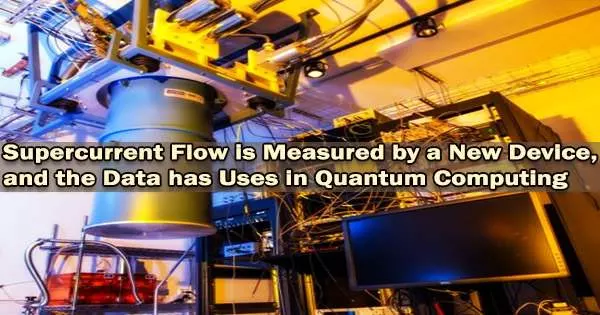

The control systems, laser source, the maze of mirrors that create an optical path for light pulsing at trillions of cycles per second, superconducting magnet surrounding the sample space, custom-built atomic force microscope, and bright yellow cryostat that lowers sample temperatures to the equivalent of liquid helium, or about -450 degrees Fahrenheit, were all pointed out and described by Wang.

Cryogenic Magneto-Terahertz Scanning Near-field Optical Microscope is how Wang refers to the device. It is situated northwest of Iowa State University’s campus in the Sensitive Instrument Facility of the Ames National Laboratory.

The apparatus was created over the course of five years using $2 million in funding, including $1.3 million from the Los Angeles-based W.M. Keck Foundation and $700,000 from Iowa State and Ames National Laboratory. It has been gathering data and contributing to experiments for less than a year.

“No one has it,” Wang said of the extreme-scale nanoscope. “It’s the first in the world.”

It can function at temperatures below that of liquid helium and in intense Tesla magnetic fields, with a focus of around 20 nanometers, or 20 billionths of a meter. That’s tiny enough to detect the superconducting characteristics of substances in these harsh conditions.

Superconductors are substances that, typically at very low temperatures, transport electricity electrons without resistance or heat. There are several uses for superconducting materials, notably in the medical field for MRI scans and as magnetic racetracks for charged subatomic particles whizzing around accelerators like the Large Hadron Collider.

We really need to measure down to that level to impact the optimization of qubits for quantum computers. That’s a big goal. And this is now only a small step in that direction. It’s one step at a time.

Professor Ilias Perakis

For quantum computing, the new generation of computing power based on the physics and energy at the atomic and subatomic scales of the quantum world, superconducting materials are now being investigated. Qubits, or superconducting quantum bits, are the brains of the novel technology. Using powerful light wave pulses is one method of managing supercurrent flows in qubits.

“Superconducting technology is a major focus for quantum computing,” Wang said. “So, we need to understand and characterize superconductivity and how it’s controlled with light.”

And that’s what the cm-SNOM instrument is doing. As described in a research paper just published by the journal Nature Physics and a preprint paper posted to the arXiv website,

Wang and a team of researchers are taking the first ensemble average measurements of supercurrent flow in iron-based superconductors at terahertz (trillions of waves per second) energy scales and the first cm-SNOM action to detect terahertz supercurrent tunneling in a high-temperature, copper-based, cuprate superconductor.

“This is a new way to measure the response of superconductivity under light wave pulses,” Wang said. “We’re using our tools to offer a new view of this quantum state at nanometer-length scales during terahertz cycles.”

Ilias Perakis, professor and chair of physics at the University of Alabama at Birmingham, a collaborator with this project who has developed the theoretical understanding of light-controlled superconductivity, said, “By analyzing the new experimental datasets, we can develop advanced tomography methods for observing quantum entangled states in superconductors controlled by light.”

The researchers’ paper reports “the interactions able to drive” these supercurrents “are still poorly understood, partially due to the lack of measurements.”

Now that those measurements are happening at the ensemble level, Wang is looking ahead to the next steps to measure supercurrent existence using the cm-SNOM at simultaneous nanometer and terahertz scales.

With support from the Superconducting Quantum Materials and Systems Center led by the U.S. Department of Energy’s Fermi National Accelerator Laboratory in Illinois, his group is searching for ways to make the new instrument even more precise.

Could measurements go to the precision of visualizing supercurrent tunneling at single Josephson junctions, the movement of electrons across a barrier separating two superconductors?

“We really need to measure down to that level to impact the optimization of qubits for quantum computers,” he said. “That’s a big goal. And this is now only a small step in that direction. It’s one step at a time.”