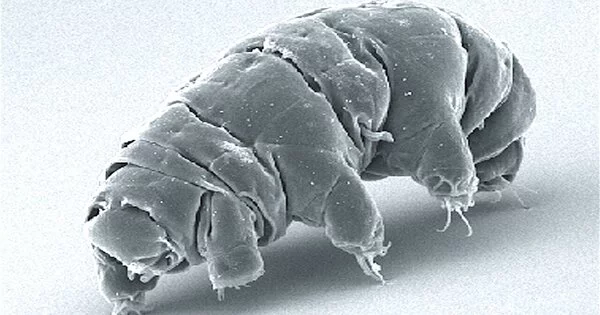

A new experiment aboard the International Space Station (ISS) is studying tardigrades, tiny creatures also known as water bears due to the way they appear under a microscope. Tardigrades can survive for decades without water in the hottest and coldest environments on Earth. The new Cell Science-04 experiment aims to identify the genes involved in water bears’ ability to survive and adapt to high-stress environments, such as the one astronaut’s experience in space. According to NASA, the findings will help guide research into protecting humans from the stresses of long-duration space travel.

The tiny tardigrade is the toughest beast on the planet. It can withstand being frozen at -272° Celsius, exposed to the vacuum of space, and even being bombarded with 500 times the dose of X-rays that would kill a human.

In other words, the creature is capable of enduring conditions that do not exist on Earth. Tardigrades are a favorite of animal lovers due to their otherworldly resilience and endearing appearance. Beyond that, scientists are looking to microscopic animals the size of a dust mite to learn how to prepare humans and crops for the rigors of space travel.

The tiny tardigrade is the toughest beast on the planet. It can withstand being frozen at -272° Celsius, exposed to the vacuum of space, and even being bombarded with 500 times the dose of X-rays that would kill a human.

The tardigrade’s indestructibility is due to adaptations to its environment, which may seem surprising given that it lives in seemingly pleasant environments, such as the cool, wet clumps of moss that dot a garden wall. Some people call tardigrades water bears or moss piglets in honor of their habitats and their pudgy appearance.

However, it has been discovered that a tardigrade’s damp, mossy habitat can dry out several times per year. Most living things are destroyed by drying. It harms cells in ways that freezing, vacuum, and radiation all do.

For one thing, drying leads to high levels of peroxides and other reactive oxygen species. These toxic molecules chisel a cell’s DNA into short fragments — just as radiation does. Drying also causes cell membranes to wrinkle and crack. And it can lead delicate proteins to unfold, rendering them as useless as crumpled paper airplanes. Tardigrades have evolved special strategies for dealing with these kinds of damage.

As a tardigrade dries out, its cells gush out several strange proteins that are unlike anything found in other animals. In water, the proteins are floppy and shapeless. But as the water disappears, the proteins self-assemble into long, crisscrossing fibers that fill the cell’s interior. Like Styrofoam packing peanuts, the fibers support the cell’s membranes and proteins, preventing them from breaking or unfolding.

At least two tardigrade species also produce another protein found in no other animal on the planet. Dsup, which stands for “damage suppressor,” is a protein that binds to DNA and may physically protect it from reactive forms of oxygen.

Emulating tardigrades could one day assist humans in colonizing space. Food crops, yeast, and insects could be genetically modified to produce tardigrade proteins, allowing these organisms to grow more efficiently on spacecraft where radiation levels are higher than on Earth.

Scientists have already inserted the gene for the Dsup protein into human cells in the lab. Many of those modified cells survived levels of X-rays or peroxide chemicals that kill ordinary cells. And when inserted into tobacco plants — an experimental model for food crops — the gene for Dsup seemed to protect the plants from exposure to a DNA-damaging chemical called ethyl methanesulfonate. Plants with the extra gene grew more quickly than those without it. Plants with Dsup also incurred less DNA damage when exposed to ultraviolet radiation.

Tardigrade “packing peanut” proteins show early signs of being human-protective. Human cells became resistant to camptothecin, a cell-killing chemotherapy agent, after being modified to produce those proteins, researchers reported in the March 18 issue of ACS Synthetic Biology. The tardigrade proteins did this by inhibiting apoptosis, a cellular self-destruct program that is frequently triggered by toxic chemicals or radiation.

If humans ever reach the stars, they may do so in part by standing on the shoulders of the tiny eight-legged endurance specialists in your backyard.