A global group of researchers, including from the colleges of Bristol and Oxford and the Normal History Gallery, have found that a very much preserved, fossilized worm dating from a long time back looks like the precursor of three significant gatherings of living creatures.

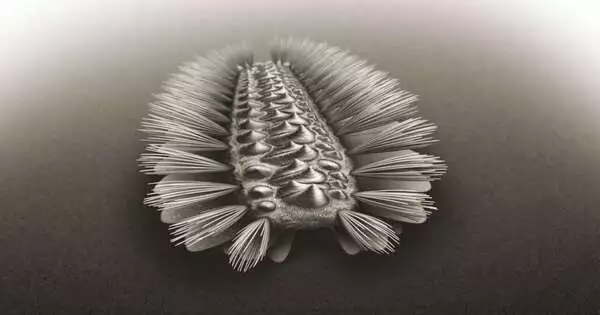

The fossil worm, named Wufengella and discovered in China, was a squat creature shrouded in a thick, routinely covering exhibit of plates on its back, sharing a home with a wiped out gathering of shelly creatures known as tommotiids.

Encompassing the uneven shield was a beefy body with a progression of leveled curves projecting from the sides. Heaps of fibers arose out of the ground in the middle between the curves and the shield. The numerous curves, heaps of fibers, and exhibit of shells on the back are proof that the worm was initially serialized or divided, similar to a night crawler.

The discoveries are accounted for now in the journal Current Science. Concentrate on co-creator, Dr. Jakob Vinther, from the College of Bristol’s School of Studies of the Planet, said, “It seems to be the improbable posterity between a fiber worm and a chiton mollusk. Curiously, it has a place in neither of those gatherings. “

“I couldn’t believe my eyes when it became evident what this fossil I was staring at under the microscope was. This is a fossil about which we have often hypothesized and hoped to one day see.”

o-author Dr. Luke Parry from the University of Oxford

The set of all animals comprises in excess of 30 significant body plans sorted as phyla. Every phylum harbors a bunch of elements that set them aside from each other. A couple of elements are shared across more than one gathering, which is a demonstration of the quick pace of development during which these significant gatherings of creatures began, called the Cambrian Blast, a long time back.

Brachiopods are a phylum that hastily looks like bivalves (like mollusks) in having a couple of shells and living attached to the ocean bottom, shakes or reefs. In any case, while peering inside, brachiopods reveal themselves to be altogether different in many regards. Truth be told, brachiopods channel water by utilizing a couple of limbs collapsed up into a horseshoe-shaped organ.

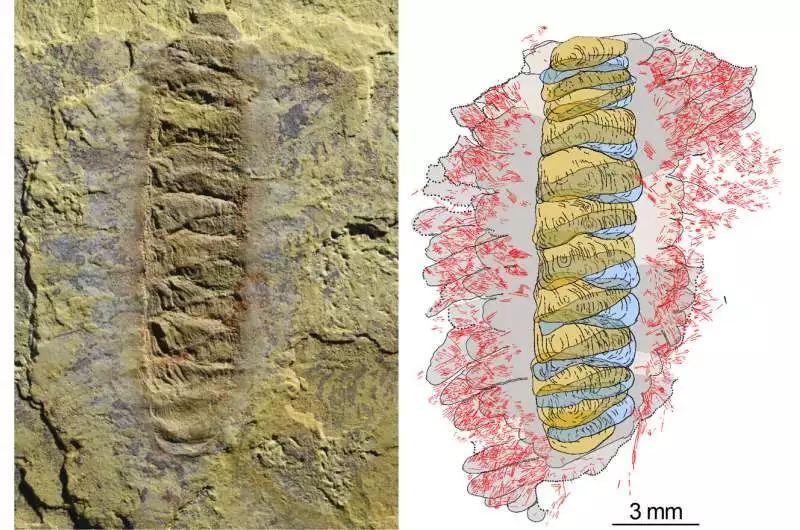

The fossil Wufengella and a drawing framing the significant parts of the creature. Photographers: Jakob Vinther and Luke Repel

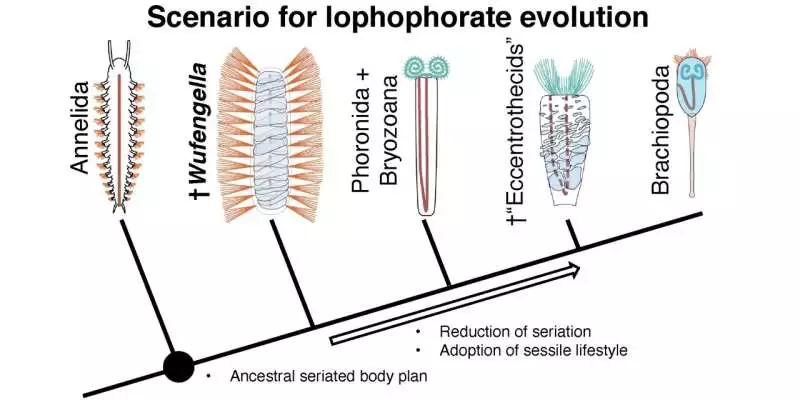

Such an organ is known as a lophophore, and brachiopods share the lophophore with two other significant gatherings called the phoronids (“horseshoe worms”) and bryozoans (“greenery creatures”). Sub-atomic examinations — which remake developmental trees utilizing amino corrosive successions — concur with physical proof that brachiopods, bryozoans, and phoronids are each other’s nearest living family members, a gathering called Lophophorata after their channel taking care of organ.

Co-creator Dr. Luke Repel from the College of Oxford added, “Wufengella has a place with a gathering of Cambrian fossils that is vital for understanding how lophophorates developed. They’re called tommotiids, and because of these fossils, we have had the option to comprehend how brachiopods developed to have two shells from precursors with many shell-like plates organized into a cone or cylinder.

“We have known for quite a while about this tomotic bunch called the Comenellans.” Scientists have felt that those shells were joined to a spry creature — creeping around — as opposed to being fixed in one spot and taken care of with a lophophore. “

The group, which comprises of scientists from the College of Bristol, Yunnan College, the Chengjiang Gallery of Normal History, the College of Oxford, the Regular History Exhibition hall in London and the Muséum public d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris, shows that Wufengella is a finished camenellan tommotiid, and that implies that it uncovers what the long sought-after diseased precursor to lophophorates seemed to be.

Dr. Repel added, “When it originally turned out to be obvious to me what this fossil was that I was taking a gander at under the magnifying lens, I was unable to trust my eyes. This is a fossil that we have frequently guessed about and trusted we would one day look at. “

While the fossil satisfies the paleontological forecast that the lophophorates’ tribal heredity was a spry, shielded worm, the presence of its delicate life systems brings into focus a few speculations about how lophophorates might be connected with divided worms.

A schematic layout of how tommotiids informs us regarding the development of body plans across the tree of life. Credit: Luke Repel.

Dr. Vinther said, “Scholars have long noticed how brachiopods have various matched body pits, novel kidney designs, and heaps of fibers on their backs as hatchlings. These likenesses drove them to see how intently brachiopods look like annelid worms. “

“We currently see that those likenesses are impressions of shared family. The normal precursor of lophophorates and annelids had a life system most notably looking like the annelids.

“Eventually, the tommotiid precursor to the lophophorates becomes sessile and takes care of (getting particles suspended in the water). Then a long, diseased body with various rehashed body units turned out to be less helpful and was decreased.

Co-creator Greg Edgecombe from the Normal History Gallery said, “This revelation features how significant fossils can be for remaking advancement.”

“We get a deficient picture by just taking a gander at living creatures, with the somewhat few physical characteristics that are divided among various phyla. With fossils like Wufengella, we can follow every ancestor back to its foundations, acknowledging the way that they once looked out and out changed and had altogether different methods of life, at times novel and now and again imparted to additional far-off family members.

More information: A Cambrian tommotiid preserving soft tissues reveals the metameric ancestry of lophophorates., Current Biology (2022). dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.cub.2022.09.011

Journal information: Current Biology