In 2020, about one-third of the world’s population did not have adequate food. That’s an increase of about 320 million people in a year, and it’s predicted to worsen as food prices rise and the war in Ukraine and Russia traps wheat, barley, and corn.

Floods, fires, and extreme weather caused by climate change, combined with armed conflict and a worldwide pandemic, have exacerbated the situation by harming the right to food.

Many people believe that world hunger is caused by “too many people and not enough food.” This cliche has been around since the 18th century, when economist Thomas Malthus predicted that the human population would soon outnumber the planet’s carrying capacity. This idea diverts attention away from the underlying causes of hunger and malnutrition.

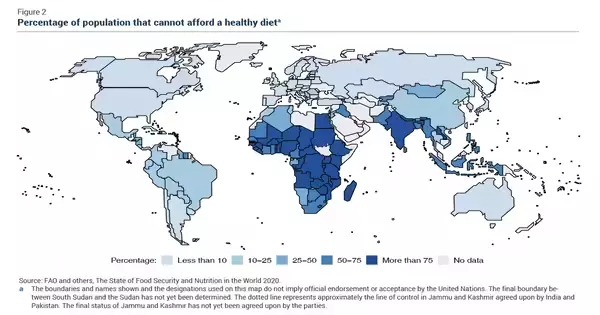

Inequity and armed conflict, on the other hand, play a larger role. The world’s hungry are disproportionately concentrated in conflict-torn Africa and Asia.

As a food system researcher who has worked on food systems since 1991, I believe that addressing core causes is the best approach to combat hunger and malnutrition. More equal distribution of land, water, and money, as well as investments in sustainable diets and peace-building, are required for this.

But how will we feed the rest of the world?

The globe generates enough food to feed more than 2,300 kilocalories per day to every man, woman, and child, which is more than enough. Poverty and inequality, however, have resulted in unequal access to the Earth’s wealth as defined by class, gender, race, and the impact of colonialism.

Sugar cane, maize, wheat, and rice account for half of global crop production, with much of it utilized for sweets and other high-calorie, low-nutrient items such as feed for industrially produced livestock, biofuels, and vegetable oil.

The global food system is dominated by a few multinational businesses that manufacture highly processed foods heavy in sugar, salt, fat, and artificial colors or preservatives. Overconsumption of these foods is killing people all around the world and putting a strain on healthcare systems.

According to nutritionists, we should minimize sugar, saturated and trans fats, oils, and simple carbohydrates and eat an abundance of fruits and vegetables, with protein and dairy making up only a quarter of our plates. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change also suggests a shift toward more sustainable and healthful diets.

According to a new study, excessive use of highly processed foods—such as soft drinks, snacks, morning cereals, packaged soups, and confectionery items—can have significant environmental and health consequences, such as Type 2 diabetes and cardiovascular problems.

Moving away from highly processed foods will also reduce their negative impacts on land, water, and energy usage.

We live in a prosperous world.

Global agricultural production has surpassed population growth since the 1960s. Despite the fact that the world’s population is peaking, the Malthusian theory continues to focus on the possibility of population growth outstripping the Earth’s carrying capacity.

Amartya Sen’s study of the Great Bengal Famine of 1943 countered Malthus by establishing that millions died of hunger because they lacked the money to buy food, not because of food shortages.

Ester Boserup, a Danish economist, questioned Malthus’ assumptions in 1970. She argues that rising earnings, gender equality, and urbanization will eventually slow the flow of population increase, with birth rates falling to or below replacement levels even in poor countries.

Food, like water, is a right, and public policy should reflect this. Unfortunately, land and income are still excessively unequally distributed, resulting in food insecurity even in prosperous countries. While land redistribution is notoriously difficult, certain land reform programs have been successful, such as the one in Madagascar.

The impact of conflict on hunger

Armed warfare exacerbates hunger. War has decimated the countries with the highest rates of food insecurity, such as Somalia. More than half of the world’s undernourished people and almost 80% of stunted-growth children live in nations afflicted by conflict, violence, or fragility.

UN Secretary General António Guterres has warned that the Ukraine conflict puts 45 African and developing nations at risk of a “cyclone of hunger,” since they import at least a third of their wheat from Ukraine or Russia. According to the New York Times, due to rising food prices, the World Food Program has been forced to reduce rations for over four million people.

In the end, proper social protection floors (basic social security guarantees) and rights-based “food sovereignty” initiatives that put people in control of their own local food systems work. In India, for example, the Deccan Development Society serves rural women by providing nutritious meals and other community services.

To solve food insecurity, we must invest in diplomacy through coordinating humanitarian, development, and peacekeeping efforts in order to avoid and reduce armed conflicts. Poverty alleviation is an important component of peacebuilding because wide-spread inequities act as tinderboxes for hostility.

Keeping our ability to create food safe

Climate change and inadequate environmental management have jeopardized collective food production assets such as soil, water, and pollinators.

Several studies conducted over the last 30 years have cautioned that soil and water contamination from high levels of pollutants such as pesticides, diminishing biodiversity, and disappearing pollinators might all have a negative impact on the quality and quantity of food supply.

A quarter of all greenhouse gas emissions are attributed to livestock, crop production, agricultural growth, and food processing. Furthermore, one-third of all food produced is lost or wasted, so addressing this atrocity is critical.

Reducing food loss and waste, as well as migrating to healthier, sustainably produced diets, will help minimize the environmental implications of the food system.

Food, health, and environmental sustainability are all intertwined.

Food is an entitlement, and it should be treated as such, rather than as a problem caused by population increase or insufficient food supply. Poverty and institutional inequality, as well as armed conflict, are the primary causes of food insecurity. It is critical to keep this concept at the forefront of conversations about feeding the globe.

To address chronic diet-related disease, environmental challenges, and climate change, we need policies that support healthy and sustainably produced, balanced meals.

More measures to promote the equitable allocation of land, water, and money are required on a worldwide scale.

We require policies that address food insecurity, such as rights-based food sovereignty systems.

In conflict-torn places, we need policies that invest in diplomacy through coordinating humanitarian, development, and peacekeeping efforts.

These are the essential approaches to understanding that “food is the single most powerful lever for optimizing human health and environmental sustainability on Earth.”