People are the main species to live in each ecological specialty on the planet—from the icesheets to the deserts, rainforests to savannahs. As people, we are fairly tiny, but when we are socially associated, we are the most predominant species on earth.

New proof from stone apparatuses in southern Africa shows these social associations were more grounded and more extensive than we had naturally suspected among our predecessors who lived quite a while back, without further ado, before the huge “out of Africa” relocation in which they started to spread across the world.

Social association and transformation.

The early people weren’t generally so associated. The main people to leave Africa vanished without this transitory achievement and without leaving any hereditary followers among us today.

Yet, for the precursors of the present individuals living beyond Africa, it was an alternate story. Within two or three thousand years, they had relocated into and adjusted to each sort of natural zone across the planet.

Archeologists believe that the improvement of informal communities and the ability to divide information among various gatherings contributed to this accomplishment.In any case, how would we notice these interpersonal organizations in the profound past?

To resolve this inquiry, archeologists inspect instruments and other human-made objects that actually endure today. We expect that individuals who made those items, similar to individuals today, were social animals who made objects with social implications.

Social network quite a while back.

A little, normal stone device offered us a chance to test this thought in southern Africa, during a period known as the Howiesons Poort, something like quite a while back. Archeologists refer to these sharp, multipurpose instruments as “supported curios,” but you can consider them a “stone Swiss Army blade”: the sort of helpful device you heft around to do different positions you can’t do manually.

These blades are not exceptional in Africa. They are tracked down across the globe and come in various shapes. This potential assortment makes these little edges so helpful to test the speculation that social associations existed a long time back.

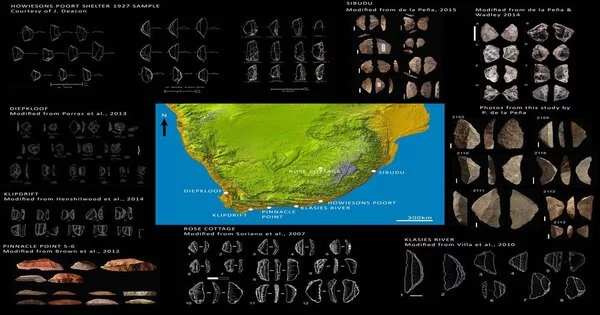

Across southern Africa, these edges might have been cut into quite a few unique shapes in better places. However, a long time ago, it turns out they were made in a very similar format across a great many kilometers and various natural specialties.

The reality that they were completely made to look so comparable focuses areas of strength for associations between geologically far-off bunches across southern Africa right now.

Critically, this shows interestingly that social associations were set up in southern Africa not long before the large “out of Africa” movement.

Comparable plans for ‘Stone Swiss Army blades’ have been tracked down across southern Africa. Author Paloma de la Pea gave credit to

Credit: Paloma de la Peña, Author provided

A valuable device in difficult situations

Beforehand, it has been thought individuals made these edges in light of different ecological burdens, on the grounds that, very much like the Swiss Army blade, they are multi-practical and multi-use.

There is evidence that stone cutting edges were frequently stuck or bound to handles or shafts to create complex devices such as lances, blades, saws, scrubbers, and bores, and they were also used as bolt tips and points.They were utilized to handle plant material, stow away quills and fur.

While the creation of the stone edge was not especially troublesome, the limiting of the stone to the handle was, including complex paste and cement recipes.

During the Howiesons Poort, these sharp edges were created in tremendous numbers across southern Africa.

Information from Sibudu Cave in South Africa shows that their peak underway happened during an exceptionally dry period, when there was less downpour and vegetation. These devices were fabricated for millennia before the Howiesons Poort, but it is during this time of changing climatic circumstances that we see a wonderful expansion in their creation.

It is the multi-usefulness and multi-use which makes this stone device so adaptable, a vital benefit for hunting and assembling in unsure or unsteady ecological circumstances.

A solid informal community adjusted to a changing environment.

Be that as it may, the development of this instrument as of now shouldn’t be seen as just a practical reaction to changing natural circumstances.

In the event that their multiplication was just a useful reaction to evolving conditions, we ought to see contrasts in various ecological specialties. Yet, what we see is likenesses in underway numbers and curio shapes across huge spans and different ecological zones.

This implies the expansion underway ought to be viewed as a component of a socially intervened reaction to changing ecological circumstances, with fortifying significant distance social ties working with admittance to scant, maybe unusual assets.

The closeness of the stone “Swiss Army blade” across southern Africa gives insight into the strength of social ties in this critical period for human development. Their similitude proposes that it was the strength of this informal organization that permitted populations to succeed and adjust to changing climatic circumstances.

These discoveries hold worldwide ramifications for understanding how extending informal communities contributed to the development of current peoples outside of Africa and into new conditions across the globe.