People and chimpanzees differ in just a single percent of their DNA. Human sped-up loci (HARs) are portions of the genome with a startling measure of these distinctions. HARs were steady in vertebrates for centuries yet immediately different in early people. Researchers have long asked why these pieces of DNA changed so much and how the varieties set people apart from different primates.

Gladstone Foundations researchers recently examined a large number of human and chimp HARs and discovered that many of the changes that occurred during human development had inhibiting effects on one another.

“This helps answer a longstanding inquiry regarding why HARs developed so rapidly after being frozen for a long period of time,” says Katie Pollard, Ph.D., head of the Gladstone Foundation of Information Science and Biotechnology and lead creator of the new review distributed today in Neuron. “An underlying variety in a HAR could have turned up its action excessively, and afterward it should have been turned down.”

“This helps to explain why HARs evolved so swiftly after being frozen for millions of years, which has been a long-standing mystery. A HAR’s original variant may have increased its activity too much, requiring it to be toned down.”

Katie Pollard, Ph.D., director of the Gladstone Institute of Data Science and Biotechnology

According to the discoveries, she has suggestions for grasping human development. Furthermore, because she and her colleagues discovered that many HARs play roles in mental health, the review suggests that variations in human HARs may predispose individuals to mental illness.

“These outcomes required state-of-the art AI devices to coordinate many novel datasets created by our group, giving another focal point to look at the development of HAR variations,” says Sean Whalen, Ph.D., first creator of the review and ranking staff research researcher in Pollard’s lab.

Enabled by machine learning

Pollard found HARs in 2006 while looking at the human and chimpanzee genomes. While these stretches of DNA are almost indistinguishable among all people, they vary among people and different vertebrates. Pollard’s lab proceeded to show that by far most HARs are not qualities but rather enhancers administrative locales of the genome that control the action of qualities.

More recently, Pollard’s gathering needed to concentrate on how human HARs differ from chimpanzee HARs in their enhancer capabilities. Before, this would have required testing HARs each in turn in mice, utilizing a framework that stains tissues when a HAR is dynamic.

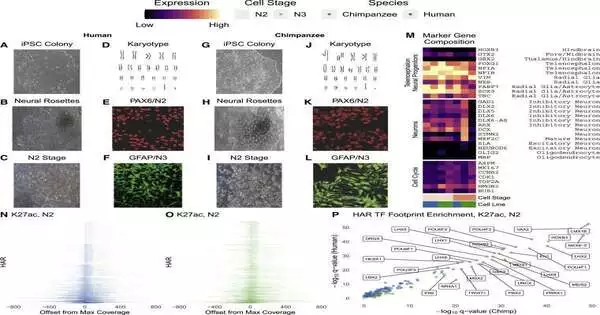

All things considered, Whalen inputted many known human mind enhancers and many other non-enhancer groupings into a PC program so it could recognize designs that anticipated whether any given stretch of DNA was an enhancer. Then he utilized the model to foresee that 33% of HARs control mental health.

“Essentially, the PC had the option to get familiar with the marks of mind enhancers,” says Whalen.

Realizing that each HAR has various contrasts among people and chimpanzees, Pollard and her group addressed what individual variations in a HAR meant for its enhancer strength. For example, in the event that eight nucleotides of DNA varied between a chimpanzee and human HAR, did each of the eight make a similar end result, either making the enhancer more grounded or more fragile?

“We’ve been wondering for a long time whether all of the differences in HARs were expected for it to work differently in people, or if a few changes were simply bums on a ride curious to see what happens with more significant ones,” says Pollard, who is also the head of the division of bioinformatics in the Branch of The Study of Disease Transmission and Biostatistics at UC San Francisco (UCSF) and a Chan Zuckerberg Biohub.

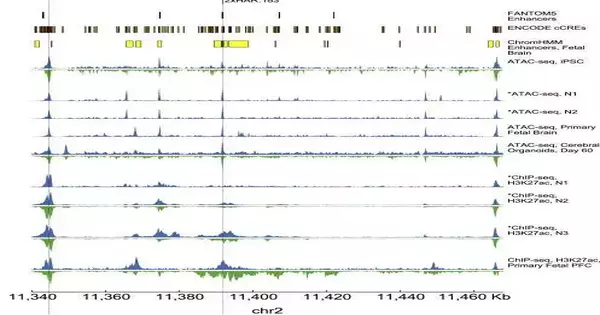

Approval of a functioning HAR enhancer managing ROCK22xHAR.

To test this, Whalen applied a subsequent AI model, which was initially intended to decide whether DNA contrasts from one individual to another influence enhancer action. The PC anticipated that 43% of HARs contain at least two variations with huge restricting impacts: a few variations in a given HAR made it a more grounded enhancer, while different changes made the HAR a more fragile enhancer.

This outcome amazed the group, who had expected that all changes would push the enhancer in a similar direction or that some “drifter” changes would not affect the enhancer by any means.

Estimating HAR strength

To approve this convincing forecast, Pollard teamed up with the labs of Nadav Ahituv, Ph.D., and Alex Dust, Ph.D., at UCSF. The scientists mated each HAR to a little DNA scanner tag. Each time a HAR was dynamic, improving the outflow of a quality, the scanner tag was translated into a piece of RNA. Then, the analysts utilized RNA sequencing innovation to dissect the amount of that scanner tag that was available in any cell, showing how dynamic the HAR had been in that cell.

“This strategy is considerably more quantitative on the grounds that we have careful scanner tag counts rather than microscopy pictures,” says Ahituv. “It’s likewise a lot higher throughput; we can check out many HARs in a solitary trial.”

When the gathering performed their lab probes north of 700 HARs in antecedents to human and chimp synapses, the data replicated what the AI calculations had predicted.

“We probably wouldn’t have found human HAR variations with restricting impacts by any means in the event that the AI model hadn’t created these alarming forecasts,” said Pollard.

Suggestions for grasping mental illness

The possibility that HAR variations played back-and-forth over enhancer levels fits in well with a hypothesis that has previously been proposed about human development: that the high level of perception in our species likewise has given us mental illnesses.

“What this sort of example shows is something many refer to as compensatory development,” says Pollard. “A huge change was made in an enhancer, yet perhaps it was excessive and prompted unsafe aftereffects, so the change was tuned down over the long runerthat is the reason we see restricting impacts.”

Pollard speculates that if initial changes to HARs resulted in increased insight, subsequent compensatory changes may have helped reduce the risk of mental illnesses.Her information, she adds, can’t straightforwardly demonstrate or negate that thought. Yet, later on, a superior comprehension of how HARs contribute to mental illness couldn’t reveal insight into the development of new medicines for these illnesses.

“We can never wind the clock back and know exactly what occurred in advance,” says Pollard. “Yet, we can utilize this multitude of logical methods to mimic what could have occurred and recognize which DNA changes are probably going to make sense of novel parts of the human mind, including its affinity for mental illness.”

More information: Sean Whalen et al, Machine learning dissection of human accelerated regions in primate neurodevelopment, Neuron (2023). DOI: 10.1016/j.neuron.2022.12.026

Journal information: Neuron