War, budget cuts, a pandemic, and an accident: for each of its preliminary tasks, Europe’s ExoMars mission may merit the name Constancy more than NASA’s Martian explorer.

Yet, the European Space Organization actually trusts the mission to send off in 2028 on its long-deferred journey to look for extraterrestrial life on the Red Planet.

This time last year, the ESA’s Rosalind Franklin wanderer was all prepared for a September sendoff from the Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan, wanting to get a ride on a Russian rocket and slide to the Martian surface on a Russian lander.

Then, in the spring, Russia attacked Ukraine, forcing the ESA’s 22 member states to withdraw and the mission to be suspended.

It was the perfect most recent blow for the many researchers who have been working on the project for over two decades.

When first considered in 2001, the aggressive program immediately demonstrated that it would be excessively costly for Europe, which has yet to land a meanderer on Mars.

NASA, the US space agency, stepped in to fill the subsidizing void in 2009.In any case, after three years, financial plan slices prompted NASA’s pulling out.

At that point, help came from a surprising source: Russia’s space organization, Roscosmos.

Together, the ESA and Roscosmos sent off the Schiaparelli EDM module in 2016 as a trial for ExoMars.

Be that as it may, when Schiaparelli showed up at Mars, a PC misfire made it collide with the surface and fall silent.

That disappointment pushed back the launch of the joint Russian-European ExoMars mission to July 2020.

The coronavirus pandemic pushed that date back to 2022, when it was again deferred by the attack on Ukraine.

Tricky Russian negotiations

Before the end of last year, the ESA’s pastoral committee consented to keep the mission bursting at the seams with an infusion of 500 million euros ($540 million) throughout the following three years.

David Parker, the ESA’s overseer of human and mechanical investigation, said last week that one of the contentions they set forward for proceeding with the mission was “that this is a one-of-a kind piece of European science.”

“It resembles James Webb,” he expressed, alluding to the space telescope that has been sending back amazing pictures of far-off worlds since around 2022.

“Yet, it’s for Mars—iit’s that size of aspiration.”

“This is the main mission that is predicted that can really track down proof of previous existence.”

Yet, a few huge obstacles remain that could make a 2028 launch troublesome, including the fact that the ESA needs a better approach to landing its wanderer on Mars.

The ESA will initially need to recuperate European parts, including a locally available PC and radar altimeter, from Russia’s Kazachok lander, which is currently at its gathering site in Turin, Italy.

Anyway, no one but Russia can extricate the parts from the lander.

Troublesome discussions have been in progress for Russian specialists to come and destroy the lander.

“We anticipated them in mid-January, however, they didn’t come,” ESA ExoMars program group pioneer Thierry Blancquaert told AFP.

“We requested that they have everything done toward the end of spring,” he added.

NASA to the rescue

To make headway, the new mission will rely on help from NASA, which has up until this point shown it is eager to assist.

For its new lander, the ESA desires to exploit US motors used to get NASA’s Interest and Determination wanderers onto the Martian surface.

It will likewise need to depend on NASA for radioisotope warmer units after losing access to Russia’s stockpile. These units keep the rocket warm.

NASA has not yet decided on a careful spending plan that would support such endeavors, yet “we are setting up the cooperative work together and things are advancing great,” Blancquaert said.

Francois Neglect, an astrophysicist at France’s CNRS logical examination community, said that “this new catalyst for participation is connected to the way that this time, the US has a joint undertaking with Europe: the Mars Test Return.”

The mission, scheduled for around 2030, will return to Earth with data collected from Mars by both ExoMars and Persistence, which landed in the world in July 2021.

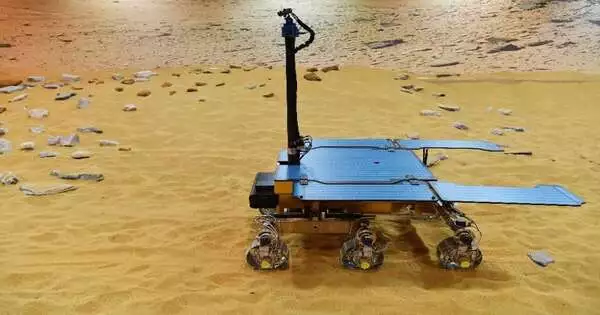

Not at all like Diligence, the Rosalind Franklin wanderer can bore up to two meters (6.5 feet) underneath the outer layer of Mars, where hints of conceivable ancient life could be better protected.

ExoMars’ arranged landing site is additionally in a space on Mars expected to have been better suited to facilitating its previous existence.

“We think there was a ton of water there,” said Neglect.

“There is one more Mars to investigate, so even in 10 years’ time, the mission won’t be outdated,” he added.