A new study led by teams from the Faculty of Biology, the Biodiversity Research Institute (IRBio) of the University of Barcelona, and the Institute of Marine Sciences (ICM-CSIC) of Barcelona has revealed that marine heatwaves associated with the climate crisis are reducing coral populations in the Mediterranean, with biomass being reduced by 80 to 90 percent in some cases.

According to the study, which was published in the journal Proceedings of the Royal Society B, coral populations in the Mediterranean, which are essential for the functioning of coral reefs, one of the sea’s most iconic habitats, may be unable to recover from the recurring impact of these extreme episodes, with water temperatures reaching high degrees for days or even weeks.

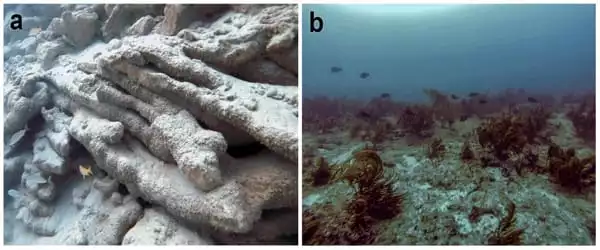

This is the first study to look at the long-term recovery potential of two iconic Mediterranean coral species: the red gorgonian (Paramuricea clavata) and the red coral (Corallium rubrum), both of which create complex environments that are crucial for a wide range of associated animals. As a result, understanding their resilience in the face of more frequent and violent heatwaves is critical.

We detected an average biomass loss of 80 percent in populations of red gorgonian, and up to 93 percent in the examined population of red coral. These data are concerning for the conservation of these iconic species, and they indicate that the effects of the climate crisis are hastening, with obvious consequences for the submarine landscapes, where the loss of coral equals the loss of trees in forests.

Daniel Gómez, researcher at ICM-CSIC

Mass mortality events

The Mediterranean’s marine ecosystems are suffering as a result of the global climate catastrophe. The marine heatwaves connected with the climate crisis, in particular, are producing mass death events in all of this basin’s coastal ecosystems, with Mediterranean corals being among the most affected.

Despite research have examined the acute impact of marine heatwaves on these creatures, knowledge on the coral’s long-term resistance remains limited. Because these are long-lived species (more than a hundred years in certain cases) with slow populational dynamics (i.e., organisms with low growth and recruitment rates), researchers require long transient series (decades) to measure their recovery potential.

The team analyzed the findings of a long-term monitoring on different populations of coral damaged by a large mass death caused by a heatwave in 2003 in the Scandola protected maritime region as part of the study (Corsega, France). They examined data on the state of these populations (density, size structure, and biomass) obtained by researchers from the MedRecover study group, which was founded by experts from the UB and ICM-CSIC, among other institutions, over the fifteen years following the heatwave.

Far from recovering, the findings suggest that all of the communities studied have been on the verge of collapsing since the 2003 heatwave. From a functional standpoint, these populations are effectively extinct fifteen years after this event.

“We detected an average biomass loss of 80 percent in populations of red gorgonian, and up to 93 percent in the examined population of red coral,” says Daniel Gómez, researcher at ICM-CSIC.

“These data are concerning for the conservation of these iconic species, and they indicate that the effects of the climate crisis are hastening, with obvious consequences for the submarine landscapes, where the loss of coral equals the loss of trees in forests,” says Joaquim Garrabou, another ICM-CSIC member.

Recurrent exposure to heatwaves

According to Cristina Linares, professor at the Faculty of Biology’s Department of Evolutionary Biology, Ecology, and Environmental Sciences and member of IRBio, “we believe one of the main reasons why we observed these collapse trajectories is the potential recurrent exposure to heatwaves, which is incompatible with the slow populational dynamics of these species.” During the study period (2003-2018), they recorded significant heatwaves in at least four years: 2009, 2016, 2017, and 2018.

“During these heatwaves,” Linares writes, “temperature conditions in the study area reached severe levels that are incompatible with the survival of these corals, likely causing new mortality events to the destroyed populations and making recovery difficult.”

Because we expect the quantity and intensity of marine heatwaves to grow in the next decades as a result of the climate crisis, the viability of many coral populations could be jeopardized.

“However, due to a variety of circumstances, the recurrence of such climate consequences is likely to be reduced in particular areas of the Mediterranean. This makes it extremely important to maintain – in terms of other potential impacts – these climate refuges where coral population trajectories may be more favorable than those reported in this study “according to the research team

“However, there is an urgent need for bolder measures to be implemented against the climate problem before biodiversity loss becomes irreplaceable,” the scientists conclude.