As of late, a never-before-seen peculiarity in a sort of quantum material could be made sense of by a progression of humming, honey bee-like “circle flows.” The discovery by physicists at the University of Colorado at Boulder (CU Boulder) may one day aid engineers in developing new types of gadgets, such as quantum sensors or what could be compared to PC memory capacity gadgets.

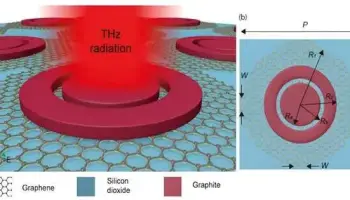

The particular quantum material being referred to is known by the compound formula Mn3Si2Te6. Nonetheless, you could likewise just refer to it as “honeycomb” on the grounds that its manganese and tellurium iotas structure an organization of interlocking octahedra that seem to be the cells in a bee colony.

“We’ve found another quantum condition of an issue. “Its quantum change is practically similar to ice softening into water.” — Prepare caco

At the point when physicist Pack Cao and his partners at CU Rock blended this sub-atomic bee colony in their lab in 2020, they were in for a shock: Under most conditions, the material acted a lot like a cover. This implies that it didn’t permit electric flows to easily go through it. In any case, when they presented the honeycomb to attractive fields with a specific goal in mind, it unexpectedly became a great many times less impervious to flows. It was as though the material had changed from elastic to metal.

“The internal loop currents circulating around the octahedra’s edges are extremely vulnerable to external currents.” When an external electric current crosses a critical threshold, the loop currents are disrupted and eventually ‘melt,’ resulting in a new electronic state.”

Physicist Gang Cao

“It was both amazing and baffling,” said Cao, referring to the creator of the new review and a teacher in the Branch of Material Science. “Our subsequent exertion in chasing after a superior comprehension of the peculiarities drove us to many additional amazing disclosures.”

He and his colleagues now acknowledge that they can make sense of that incredible way of behaving.The gathering, which incorporated a few alumni understudies at CU Rock, distributed its latest outcomes in the journal Nature on October 12.

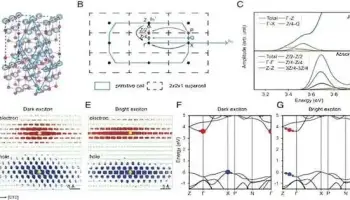

Attracting on tests in Cao’s lab, the exploration bunch reports that, under specific circumstances, the honeycomb is buzzing with small, inner flows known as chiral orbital flows, or circle flows. Electrons zoom around in circles inside each of the octahedra in this quantum material. Since the 1990s, physicists have guessed that circle flows could exist in a small bunch of materials, for example, high-temperature superconductors, yet they still can’t seem to straightforwardly notice them.

Cao believes they are capable of causing alarming changes in quantum materials such as the one he and his colleagues are working on.

“We’ve found another quantum condition of an issue,” Cao said. “Its quantum change is practically similar to ice softening into water.”

The review homes in on an odd property in material science called huge magnetoresistance (CMR).

During the 1950s, that’s what physicists understood: assuming they uncovered specific sorts of materials for magnets that create an attractive polarization, they could make those materials go through a shift—mmaking them change from covers to more wire-like channels. Today, this innovation appears in PC hard drives and numerous other electronic gadgets where it assists with controlling and transporting electric flows in particular ways.

Nonetheless, the honeycomb being referred to is immensely unique in relation to those materials; the CMR happens just when conditions keep away from that equivalent sort of attractive polarization. Cao added that the change in electrical properties is likewise considerably greater than what you can find in some other known CMR materials.

“You need to abuse every one of the regular circumstances to accomplish this change,” Cao said.

Melting ice

He and his partners, including CU Rock graduate understudies Yu Zhang, Yifei Ni, and Hengdi Zhao, needed to find out why.

They, alongside co-creator Itamar Kimchi of the Georgia Foundation for Innovation, hit on circle flows. As per the group’s hypothesis, endless electrons flow around inside their honeycombs consistently, following the edges of every octahedron. Without an attractive field, those circle flows will generally remain messy or stream in both clockwise and counterclockwise examples. It’s similar to vehicles passing through a traffic circle in both directions at the same time.

That issue can cause “gridlocks” for electrons going into the material, Cao said, expanding the opposition and making the honeycomb a cover.

As Cao put it: “Electrons like requests.”

The physicist added, in any case, that assuming you pass an electric flow into the quantum material within the sight of a particular sort of attractive field, the circle flows will start to course just in one direction. Gridlocks are eliminated in an unexpected way.When that occurs, electrons can speed through the quantum material as though it were a metal wire.

“The inner circle flows coursing along the edges of the octahedra are unusually helpless in the face of the outer flows,” Cao explained.”At the point when an outer electric flow surpasses a basic edge, it upsets and at last “softens” the circle flows, prompting an alternate electronic state.”

He noticed that in many materials, the change from one electronic state to another happens quickly, in the range of trillionths of a second. Yet in his honeycomb, that change can take seconds or much longer to happen.

Cao associates the whole design with the honeycomb starting to transform, with the connections between iotas breaking and changing in new examples. That sort of reordering requires some investment, he noted—a piece like what happens when ice softens into water.

Cao said the work gives another worldview to quantum advances. For the present, you likely won’t see this honeycomb in any new electronic gadgets. This is due to the fact that the exchange of conduct only occurs at cold temperatures.He and his partners, nonetheless, are looking for comparable materials that will do exactly the same thing under considerably more cordial circumstances.

“To include this in later gadgets, we want to have materials that show a similar sort of conduct at room temperature,” Cao said.

Presently, that kind of creation could be buzz-commendable.

Reference: “Control of chiral orbital currents in a colossal magnetoresistance material” by Yu Zhang, Yifei Ni, Hengdi Zhao, Sami Hakani, Feng Ye, Lance DeLong, Itamar Kimchi and Gang Cao, 12 October 2022, Nature.

DOI: 10.1038/s41586-022-05262-3