NASA’s New Horizons mission will examine the furthest distant object ever visited by a spacecraft in less than ten weeks.

New Horizons will ring in the New Year by flying past the Kuiper Belt object (KBO) 2014 MU69, also known as Ultima Thule, a city-size rock thought to be a frozen relic from the formation of the solar system, in the early morning hours of January 1, 2019.

Scientists have a general estimate of Ultima Thule’s dimensions, which is around 23 miles (37 kilometers) broad, but they don’t have much more information. They don’t know if it’s elongated, if it has a moon or a ring system, or if it’s even a single object. Indeed, some of the relatively few sightings of Ultima Thule imply that it may be two planets orbiting in close proximity.

“Really, we have no idea what to expect,” New Horizons principal investigator Alan Stern, of the Southwest Research Institute in Boulder, Colorado, said during a news conference here yesterday (Oct. 24) at the American Astronomical Society’s Division for Planetary Sciences meeting.

However, just as the probe removed the veil on Pluto during its historic flyby in July 2015, New Horizons should expose Ultima Thule’s mysteries.

Not only will New Horizons provide information about Ultima Thule’s size, surface, and prospective orbital companions, but it will also benefit planetary scientists in their understanding of how the solar system formed, according to Stern.

“Whatever we do, it’s going to be historic,” he said.

Ten weeks out from Pluto, we could already resolve the disk. Each week, we waited to see more and more detail. But Ultima Thule 10 weeks out is just a dot in the distance, and it will remain a dot in the distance until literally the day before the flyby, when we start to resolve it.

Alan Stern

“A dot in the distance”

As New Horizons approached Pluto more than three years ago, its pictures revealed more and more information about the dwarf planet. Ultima Thule, on the other hand, is significantly smaller than Pluto, with a diameter of 1,477 miles (2,377 kilometers).

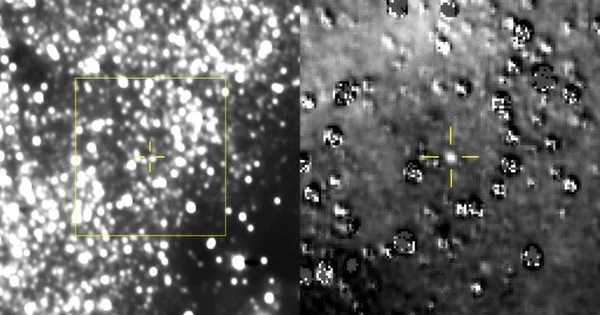

“Ten weeks out from Pluto, we could already resolve the disk. Each week, we waited to see more and more detail,” Stern said. “But Ultima Thule 10 weeks out is just a dot in the distance, and it will remain a dot in the distance until literally the day before the flyby, when we start to resolve it.”

On Jan. 1, New Horizons will fly by Ultima Thule at a speed of 20,000 mph (32,000 km/h), giving it a brief glimpse. Scientists, on the other hand, will extract as much information as possible from the encounter.

The KBO will be examined by all seven of New Horizons’ research equipment, which will probe its surface for suggestions about its composition and evidence of cometary activity. The surface will be explored with a high-resolution camera, and the rotational properties of Ultima Thule will be measured by the spacecraft.

“We’ll be making extremely intensive investigations of the environment around Ultima Thule” by late November and early December, said Hal Weaver, a New Horizons team member at the Johns Hopkins Applied Physics Laboratory (APL), during yesterday’s news conference.

Those observations will look for moons, dust rings, or debris rings that could injure the spacecraft during the flyby. Weaver said the crew has until Dec. 16 to determine whether to make the close flyby they want (2,175 miles, or 3,500 kilometers) or buzz Thule from a safer distance (6,200 miles, or 10,000 kilometers).

For perspective, New Horizons got within 7,800 miles (12,500 km) of Pluto in July 2015.

“We can still have a fantastic mission but avoid damage to the spacecraft,” Weaver said.

Weaver said the final photographs that New Horizons broadcasts home before the close approach will be akin to the view of Pluto that NASA’s Hubble Space Telescope can now get, which is only a few pixels across.

“Wait until afterwards that’s when the real rich dataset is going to come down,” he said.

New Horizons won’t be able to connect with Earth once it spins to target its equipment at Ultima Thule. After closest approach, the probe will stay locked on the KBO for a while to measure the object’s nighttime temperatures, which can offer information about how heat moves across its surface.

Plasma and dust sensors will also monitor the nearby environment around Ultima Thule. Stern and his colleagues don’t expect to find an atmosphere or any evidence of ongoing geological processes in the tiny rock, but they plan to investigate nevertheless.

“If we find recent activity in an object this small, that would be very large-point headlines, because we would not understand how that could happen,” Stern said.

The probe will rotate and transmit home a signal several hours after the close encounter to inform its Earth followers that it survived its close approach with Ultima Thule. According to mission team members, the signal will take over 6 hours to reach mission control.

New Horizons will deliver some of the greatest photographs and measurements from the flyby on January 2 and 3. According to mission team members, the photographs will have a higher resolution than the ones taken by the spacecraft of Pluto.

New Horizons took around 16 months to return all of the data from its Pluto flyby. It will take significantly longer to get all of the Ultima Thule photos on the ground.

“Data will be coming down through all of 2019 and most of 2020,” Stern said.

The 50 gigabits of data collected during the flyby will be transmitted at a rate of just over 1,000 bits per second by the spacecraft. Carey Lisse, another New Horizons scientist from APL, compared it to the days of dial-up, when images would load row by row.

“Except you weren’t dialing up from 4 billion miles away,” Stern said.

“Far out”

“Ultima Thule” means “beyond the farthest frontiers,” according to Stern, and the frigid rock definitely is. It will not only be the first item analyzed deep inside the Kuiper Belt, but it will also be the farthest away cosmic object ever explored, more than 40 times further from the sun than Earth orbits.

“This will be our first ground truth, our first close look at what makes these Kuiper Belt objects dark and red,” New Horizons team member Kelsi Singer, also of SWRI, said during yesterday’s news conference. “That will be important for understanding these objects.”

Understanding the ices at the solar system’s boundary will reveal a surprising amount about our own planet. The material left over after planet formation is stored in the Kuiper Belt. We’ll gain a glimpse into the same materials that helped construct Earth and its siblings by examining Ultima Thule, according to Stern.

“New Horizons is going to have the capability in the space of one week, the first week of January 2019, to confirm or refute the very models of solar system formation presented here at the Division of Planetary Sciences meeting,” Stern said.

The flyby should also shed light on a riddle behind the KBO’s unusual brightness. Despite its icy coating, Ultima Thule is nearly as dark as coal, like most rocky objects in the outer solar system. That’s because it’s been cooked for ages by cosmic radiation, according to Lisse. Ultima Thule, on the other hand, is a touch brighter than it should be.

“There’s something going on that makes it twice as bright as your average comet nuclei,” Lisse said. Hopefully, New Horizons will uncover what makes the tiny target shine.

Scientists are still unsure what New Horizons will reveal as it flies past Ultima Thule in a few of weeks. However, they are eager to learn more about the solar system’s mysteries.

“There’s one thing you can say about Ultima Thule for sure,” Stern said. “It’s far out.”