At the beginning of the new millennium, just over two decades ago, it appeared that our ancestors’ more than 50,000-year-old footprints were exceedingly uncommon.

At that point, there had only been four reports of sites across all of Africa. Two were from East Africa: Koobi Fora in Kenya and Laetoli in Tanzania; Nahoon and Langebaan, both from South Africa, were the others. In fact, the first hominin tracksite ever described was the Nahoon site, which was discovered in 1966.

In 2023, the circumstances will be altogether different. It would appear that people weren’t looking in the right places or with enough focus. 14 hominin ichnosites (a term that includes both tracks and other traces) dating back more than 50,000 years have been found in Africa today. These are easily separated into an East African cluster with five sites and a South African cluster with nine sites on the Cape Coast. There are an additional ten locations outside of the United Kingdom and the Arabian Peninsula.

The traces left by our human ancestors as they moved through ancient landscapes are a useful way to complement and enhance our understanding of ancient hominins in Africa because there have been relatively few skeletal hominin remains discovered on the Cape Coast.

We provided the ages of seven newly dated hominin ichnosites that we have identified over the course of the past five years on the Cape South Coast of South Africa in an article that was recently published in Ichnos, the international journal of trace fossils. The nine sites that make up the “South African cluster” now include these locations.

We found that the destinations varied in age; the most recent one is approximately 71,000 years old. The most seasoned, which goes back 153,000 years, is one of the more exceptional tracks kept in this review: It is the oldest footprint that our species, Homo sapiens, has found.

The archaeological record is supported by the new dates. It confirms that the Cape South Coast was an area where early anatomically modern humans survived, evolved, and thrived before spreading out of Africa to other continents. Other evidence from the area and time period includes the creation of sophisticated stone tools, art, jewelry, and shellfish harvesting.

Sites that are very different

The South African and East African tracksite clusters differ significantly. The sites in East Africa are much older. The youngest, 0.7 million-year-old Laetoli, is the oldest, at 3.66 million years old. The tracks were made by earlier species like Australopithecines, Homo heidelbergensis, and Homo erectus, not by Homo sapiens. The surfaces on which the East African tracks typically occur have required extensive and laborious excavation and exposure.

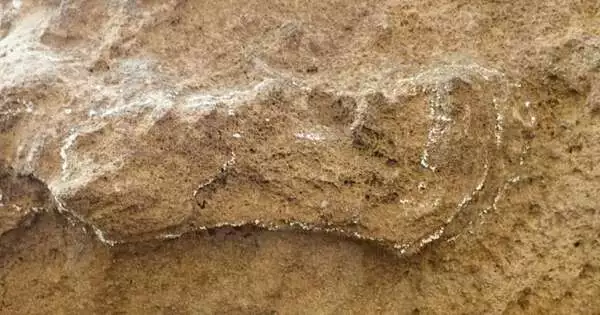

On the other hand, the South African sites along the Cape Coast are much older. Homo sapiens is credited with everything. Additionally, when they are discovered in rocks that are referred to as aeolianites—cemented versions of ancient dunes—the tracks frequently have their entire surface exposed.

Because of their exposure to the elements and the relatively coarse nature of dune sand, the sites are typically not as well preserved as the East African sites. As a result, excavation is rarely considered. They are likewise defenseless against disintegration, so we frequently need to work quickly to record and break them down before they are obliterated by the sea and the breeze.

We are able to have the deposits dated, but this limits the possibility of in-depth interpretation. Optically stimulated luminescence comes into play here.

A method that sheds light on the subject

One of the most difficult aspects of studying the palaeo-record—trackways, fossils, or any other kind of ancient sediment—is figuring out how old the materials are.

Without this, interpreting the climatic changes that create the geological record and determining the find’s overall significance are difficult. Optically stimulated luminescence is frequently the method of choice for dating the Cape South Coast aeolianites.

A grain of sand’s age can be determined using this method of dating—that is, how long that particular piece of sediment has been buried. It is a good method because we can be reasonably sure that the dating “clock” began approximately at the same time the trackway was created, given how the tracks in this study were formed—impressions made on wet sand, followed by burial with new blowing sand.

Optically stimulated luminescence works best on the south coast of Cape Cod. First, there are a lot of quartz grains in the sediments, which give off a lot of light. Second, any pre-existing luminescence signals are completely eliminated prior to the burial event of interest because of the abundant sunshine, wide beaches, and ready wind transport of sand to form coastal dunes. This makes age estimates accurate. A lot of the dating of previous finds in the area has been based on this method.

Our findings for the hominin ichnosites, which range in age from about 153,000 to 71,000 years, are in line with the ages that have been reported in previous studies of similar geological deposits in the region.

The 153,000-year-old track was discovered in the Garden Route National Park, west of Knysna, a Cape South Coast coastal town. Nahoon and Langebaan, two previously dated South African sites, have yielded ages of approximately 124,000 years and 117,000 years, respectively.

Increased comprehension

The work of our research team, which is based at Nelson Mandela University in South Africa’s African Centre for Coastal Palaeoscience, is not finished.

On the Cape’s south coast and other parts of the coast, we have a strong suspicion that additional hominin ichnosites are awaiting discovery. The hunt additionally should reach out to more established stores in the area, going in age from 400,000 years to multiple million years.

We anticipate that the list of ancient hominin ichnosites will be much longer in a decade and that scientists will be able to learn a lot more about our ancestors and the landscapes they lived in.

More information: Charles W. Helm et al, Dating the Pleistocene hominin ichnosites on South Africa’s Cape south coast, Ichnos (2023). DOI: 10.1080/10420940.2023.2204231