The age of the oldest fossils in eastern Africa widely accepted to represent our species, Homo sapiens, has long been debated. The dating of a massive volcanic eruption in Ethiopia has revealed that it is much older than previously thought.

The Omo I remains were discovered in Ethiopia in the late 1960s, and scientists have been attempting to precisely date them ever since, using the chemical fingerprints of volcanic ash layers found above and below the sediments in which the fossils were discovered.

An international team of scientists led by the University of Cambridge has recalculated the age of the Omo I skeleton – and of Homo sapiens as a species. Previous attempts to date the fossils suggested they were less than 200,000 years old, but new research indicates they must be older than a massive volcanic eruption 230,000 years ago. The findings were published in the journal Nature.

The Omo I remains were discovered in southwestern Ethiopia, within the East African Rift Valley, in the Omo Kibish Formation. The region has a high level of volcanic activity and is a rich source of early human remains and artifacts like stone tools. Scientists identified Omo I as the earliest evidence of our species, Homo sapiens, by dating the layers of volcanic ash above and below where archaeological and fossil materials were discovered.

“Using these methods, the generally accepted age of the Omo fossils is under 200,000 years, but there has been a lot of uncertainty around this date,” said Dr Céline Vidal, lead author of the paper from Cambridge’s Department of Geography. “The fossils were discovered in a sequence beneath a thick layer of volcanic ash that no one had been able to date using radiometric techniques due to the ash’s fine-grained nature.”

Our forensic approach provides a new minimum age for Homo sapiens in eastern Africa, but the challenge remains to provide a cap, a maximum age, for their emergence, which is widely believed to have occurred in this region.

Professor Christine Lane

Vidal and her colleagues have been attempting to date all of the major volcanic eruptions in the Ethiopian Rift around the time of the emergence of Homo sapiens, a period known as the late Middle Pleistocene, as part of a four-year project led by Professor Clive Oppenheimer.

The scientists collected pumice rock samples from volcanic deposits and ground them down to sub-millimetre sizes. “Each eruption has its own fingerprint — its own evolutionary story beneath the surface, which is determined by the magma’s path,” Vidal explained. “Once the rock is crushed, the minerals within are liberated, and you can date them and identify the chemical signature of the volcanic glass that holds the minerals together.”

The researchers used new geochemical analysis to connect the fingerprint of the thick volcanic ash layer from the Kamoya Hominin Site (KHS ash) with an eruption of Shala volcano, which is located more than 400 kilometers away. The team then dated volcanic pumice samples to 230,000 years ago. Because the Omo I fossils were discovered deeper than this ash layer, they must be older than 230,000 years.

“At first, I discovered a geochemical match, but we didn’t know the age of the Shala eruption,” Vidal explained. “I immediately sent the Shala volcano samples to our colleagues in Glasgow so that they could determine the age of the rocks. I was ecstatic when I received the results and discovered that the oldest Homo sapiens from the region was older than previously thought.”

“The Omo Kibish Formation is an extensive sedimentary deposit that has been barely accessed and investigated in the past,” said co-author and co-leader of the field investigation Professor Asfawossen Asrat, who is currently at BIUST in Botswana. “By delving deeper into the stratigraphy of the Omo Kibish Formation, particularly the ash layers, we were able to push the age of the region’s oldest Homo sapiens to at least 230,000 years.”

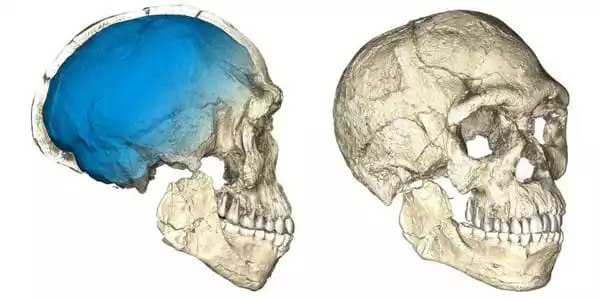

“Unlike other Middle Pleistocene fossils thought to belong to the early stages of the Homo sapiens lineage, Omo I possesses unequivocal modern human characteristics, such as a tall and globular cranial vault and a chin,” said co-author and Musée de l’Homme in Paris co-author Dr Aurélien Mounier. “The new date estimate, de facto, makes it Africa’s oldest unchallenged Homo sapiens.”

While this study establishes a new minimum age for Homo sapiens in eastern Africa, the researchers believe that new discoveries and studies may extend our species’ age even further back in time.

“We can only date humanity based on the fossils that we have, so it’s impossible to say that this is the definitive age of our species,” Vidal said. “The study of human evolution is always in motion: boundaries and timelines shift as our understanding improves. But these fossils demonstrate how resilient humans are: that we survived, thrived, and migrated in an area prone to natural disasters.”

“It’s probably no coincidence that our ancestors lived in such a geologically active rift valley — it collected rainfall in lakes, providing fresh water and attracting animals, and it served as a natural migration corridor stretching thousands of kilometers,” Oppenheimer said. “The volcanoes provided fantastic materials for making stone tools, and when large eruptions transformed the landscape, we had to develop our cognitive skills.”

“Our forensic approach provides a new minimum age for Homo sapiens in eastern Africa, but the challenge remains to provide a cap, a maximum age, for their emergence, which is widely believed to have occurred in this region,” said co-author Professor Christine Lane, head of the Cambridge Tephra Laboratory, where much of the work was carried out. “It’s possible that new discoveries and studies will extend the age of our species even further back in time.”

“There are many other ash layers we’re trying to correlate with Ethiopian Rift eruptions and ash deposits from other sedimentary formations,” Vidal explained. “Over time, we hope to better constrain the age of other fossils in the region.”