In what’s currently China, Jeholornis was a raven-sized bird that lived a long time ago, among the earliest instances of dinosaurs developing into birds. The fossils that have been found are finely saved yet crushed, the aftereffect of layers of silt being kept throughout the long term. That implies that nobody’s had the option to get a decent glance at Jeholornis’ head. Yet, in another review, scientists carefully remade a Jeholornis skull, uncovering insights regarding eyes and mind, shedding light on its vision and feeling of smell.

“Jeholornis is my favorite Cretaceous bird; it has a ton of strange, crude qualities, and it helps shed light on the greater story of how various birds developed,” says Jingmai O’Connor, partner keeper of fossil reptiles at the Field Gallery and one of the creators of the paper depicting the disclosure in the Zoological Diary of the Linnean Culture. “This study is whenever we’re first truly getting at what this bird’s skull resembled, what its mind probably was like, which is truly energizing.”

The concentrate’s most memorable creator, Han Hu, went through about 100 fossils at China’s Shandong Tianyu Gallery of Nature and chose the one with the best-saved skull — still somewhat leveled, yet flawless. We were unable to select the best example because of the high cost of thorough investigation.In any case, I picked this one on the grounds that, basically from the uncovered surface, it is somewhat finished, and what is likewise significant is that this skull is saved to be secluded from different pieces of its body, “says Hu, a scientist at the Branch of Studies of the planet, College of Oxford, UK.

“Jeholornis is my favorite Cretaceous bird; it has a lot of odd, basic characteristics, and it helps shed light on the larger tale of how different birds evolved,”

Jingmai O’Connor, associate curator of fossil reptiles at the Field Museum

“This is useful since we typically won’t hack the skull off from the skeleton to hurt these past fossils, yet a confined skull will lessen the size of the checking region, which will improve the filtering quality a ton. Fortunately, the example we chose here for this task is almost an ideal one—it gave us a lot of obscure data after the computerized remaking. “

“These bones were similar to the lower part of a sack of potato chips—they weren’t totally squashed, yet the pieces were compacted,” says O’Connor. “So we had the option to CT check them—basically taking a lot of X-beams and stacking them together to frame a 3D picture—and afterward carefully re-articulate them and remake the skull from this multitude of bones.”

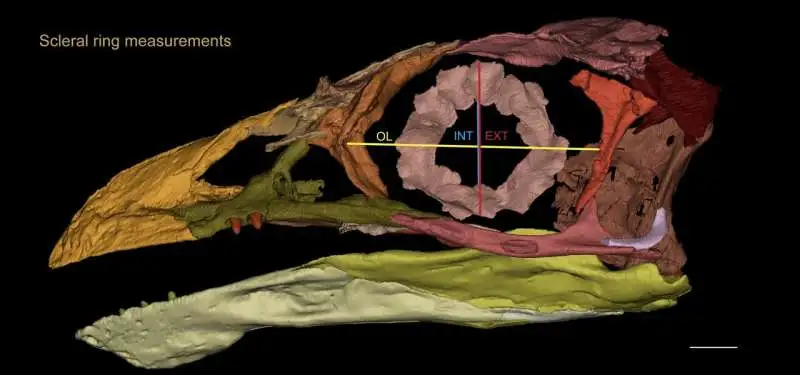

Remaking of Jeholornis’ skull, showing the hard rings around its eyes. Credit: Han Hu et al.

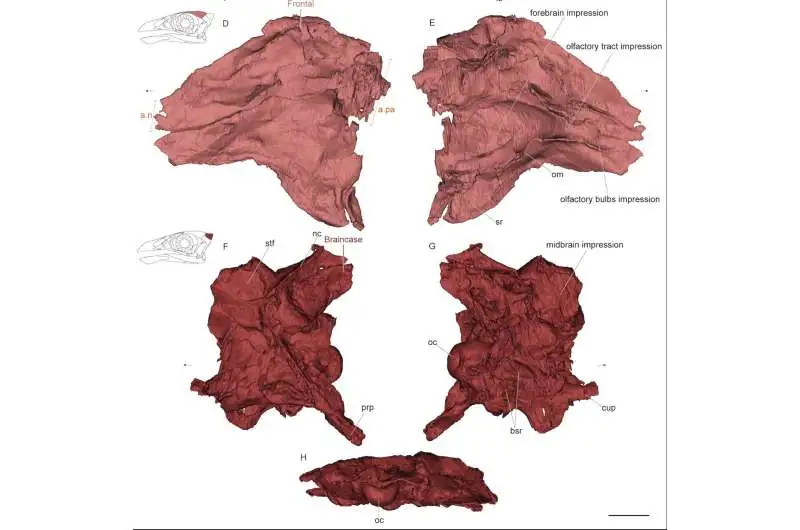

“We had the option to see various elements of the skull that had never been seen before in Jeholornis, and we were even ready to extrapolate what its mind resembled,” says co-writer and Field Gallery postdoctoral analyst Matteo Fabbri.

The actual mind isn’t saved — delicate tissues seldom are — yet bird and dinosaur cerebrums will generally settle perfectly inside their skulls. Hence, knowing the shape and aspects of a fossil bird’s skull lets us know a ton about its mind, similar to how a glove gives a fair guess of how a hand is formed. Furthermore, mind structures are preserved across species and after some time—things like olfactory bulbs and the cerebellum are in similar general spots whether you’re taking a gander at the cerebrum of a frog, a human, or a fossil bird.

Because of the well established positions of these designs, the analysts had the option to decide how Jeholornis’ mind contrasts with current birds and dinosaurs (or, rigorously speaking, non-avian dinosaurs; all birds, including Jeholornis, are dinosaurs, yet not all dinosaurs are birds).

“Jeholornis’ mind morphology is in the middle between what we see in non-avian dinosaurs and what we find in current birds,” says Fabbri. Assuming you take a gander at the skulls of dinosaurs, what you see is a spot for a very reptile-like mind, implying that they have huge olfactory bulbs, and the optic curves that are in the midbrain are decreased. They likely had an excellent sense of smell and not an incredible sight, which is reptilian. Also, then again, assuming you see current birds, they do the converse. They have little olfactory bulbs and huge optic curves. Jeholornis falls in the center. “

Jeholornis’ mind in 3D remade. Credit: Han Hu et al.

Jeholornis had greater olfactory bulbs than most current birds, implying that it presumably depended more on its sense of smell than birds today (except for a couple of sharp smellers, similar to vultures). Jeholornis’ solid feeling of smell seems OK with regards to one more late concentrate by the group. It is the earliest-known natural product-eating creature to show that Jeholornis. “As organic products age, they release heaps of synthetics,” says O’Connor. “We can’t demonstrate it yet, but having a superior sense of smell could have assisted Jeholornis with tracking down organic products.”

Notwithstanding a mind adjusted for smelling, the scientists observed that Jeholornis was better at finding in the daytime than around evening time. Birds have scleral rings, which help them decide how much light they receive.Species that need to see around evening time, similar to owls, have more extensive scleral ring openings compared with their eye attachments to allow in more light; birds that are dynamic during the day have smaller openings for light to go through, similar to the gap on a camera. Jeholornis’ scleral rings appear to show that it was generally dynamic during the day.

These skull highlights give a superior understanding of this timely riser’s way of life and the job it played in its environment. “Remaking a skull is careful work, and as individuals are beginning to invest the energy to make it happen, it’s turning out to be increasingly more certain that the development of birds was surprisingly muddled,” says Fabbri. It’s not only not the same as dinosaurs and current birds, it’s unique in relation to other early people as well. It’s anything but a clear developmental story. “

“Equivalent to Jingmai, Jeholornis is likewise one of my top birds. “Its unique situation as one of the most crude birds during the dinosaur-bird change verifies that finishing its story will uncover the genuine view of that basic developmental period, and furthermore, explain to us why and how the advanced birds — the main living dinosaurs — advanced to be what we see presently,” says Hu.

More information: Han Hu et al, Cranial osteology and palaeobiology of the Early Cretaceous bird Jeholornis prima (Aves: Jeholornithiformes), Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society (2022). DOI: 10.1093/zoolinnean/zlac089

Journal information: Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society