When people and creatures face what is going on or an issue, they normally have a general idea of how to move toward it. For example, while strolling into a shop, people will realize that they ought to tell a shop partner what they are searching for or basically peruse the items available, pay for any things they wish to buy, and leave. Essentially, a creature could understand what to do within the sight of a hunter, a likely mate, or while attempting to accumulate food in a particular climate.

This overall thought of how to move toward a given issue or circumstance comes from previous encounters or procured information. While many examinations have attempted to determine the brain underpinnings of this capacity to apply past information to the particulars of other circumstances, many inquiries remain unanswered.

A group of scientists at the College of Oxford and College School London have as of late revealed some new insights into the brain processes fundamental to the capacity of people and creatures to adjust the manner in which they approach issues in light of previous encounters. Their paper, published in Nature Neuroscience, features the critical roles of two key cerebral locales, in particular the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus.

In their paper, they wrote, “People and different creatures easily sum up earlier information to take care of novel issues by abstracting normal construction and planning it onto new sensorimotor points of interest.” Veronika Samborska, James L. Head, Imprint E. Walton, Timothy E. J. Behrens, and Thomas Akam wrote in their paper. “To research how the cerebrum accomplishes this, we prepared mice for a progression of inversion learning issues that had a similar design yet had different actual executions.”

“By abstracting common structure and projecting it onto new sensory specifics, humans and other animals effortlessly generalize existing knowledge to solve novel difficulties. We trained mice on a series of reversal learning problems with the same structure but different physical implementations to study how the brain accomplishes this.”

Veronika Samborska, James L. Butler, Mark E. Walton, Timothy E. J. Behrens, and Thomas Akam wrote in their paper.

In their trials, Samborska and her partners wished to test the speculation that while a creature is handling an issue, preoccupied or schematic portrayals in the prefrontal cortex are deftly connected with sensorimotor qualities of the climate that the creature is in. This permits the creature to develop substantial portrayals of the assignment they completed in the hippocampus, which can then be recovered while handling comparative errands or when in comparable conditions.

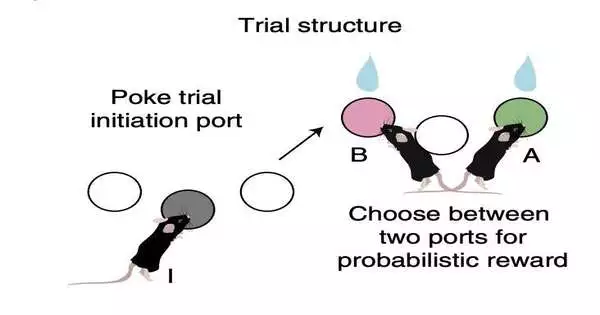

To do this, the scientists uncovered a gathering of mice to a progression of issues with a similar dynamic construction, but with somewhat unique actual areas of things. They then kept single units in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus while the mice handled these issues and analyzed the neuronal portrayals coming about because of every preliminary, both in the average prefrontal cortex and in the hippocampus.

As they had expected, the mice’s capacity to handle new yet comparable issues was reliably worked on after some time, which suggests that they had the option to apply the information they procured in past preliminaries to new ones. Their findings also distinguish differences between neuronal portrayals delivered in the mPFC and those created in the hippocampus as the mice were handled in the experiment.

Samborska and her partners made sense of this in their paper. “Neurons in average prefrontal cortex (mPFC) kept up with comparative portrayals across issues regardless of their different sensorimotor associates, while hippocampal (dCA1) portrayals were all the more firmly impacted by the particulars of every issue,” Samborska and her partners wrote. “This was valid for the two portrayals of the occasions that involved every preliminary and those that incorporated decisions and results over numerous preliminaries to direct a creature’s choices.”

The new discoveries accumulated by this group of specialists offer new important understanding about the functions of the PFC and hippocampus in the capacity of creatures to handle new issues in light of earlier information. Later on, their work could prepare for new examinations by looking at the corresponding jobs of these two cerebrum areas further, working on the understanding of how the exchange of earlier information to new errands happens in the mind.

Samborska and her associates wrote in their paper. “The information proposes that prefrontal cortex and hippocampus assume correlative parts in the speculation of information: PFC abstracts the normal construction among related issues, and the hippocampus maps this design onto the particulars of the ongoing circumstance,” Samborska and her associates wrote in their paper.

More information: Veronika Samborska et al, Complementary task representations in hippocampus and prefrontal cortex for generalizing the structure of problems, Nature Neuroscience (2022). DOI: 10.1038/s41593-022-01149-8

Journal information: Nature Neuroscience