An asphalt-and-clay pond strewn like a massive swimming pool atop a hill overlooking Lake Michigan holds enough water to power 1.6 million homes.

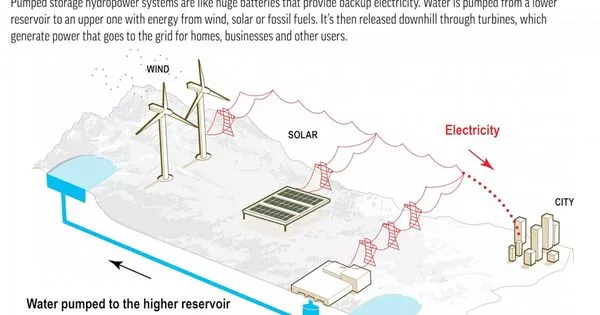

It’s part of the Ludington Pumped Storage Plant, which employs straightforward technology: water is transported from a lower reservoir—in this case, the lake—to an upper reservoir, then discharged downhill via supersized turbines.

Supporters refer to these systems as “the world’s largest batteries” since they store massive amounts of potential energy for use by the power grid when needed.

Pumped storage, according to the hydropower sector, is the best answer to a conundrum that has hung over the shift from fossil fuels to renewable energy to address climate change: where to get power when the sun isn’t shining or the wind isn’t blowing.

I wish we could construct ten more of these. I adore them, “Consumers Energy’s community affairs manager, Eric Gustad, stated during a tour of the Ludington facility.

However, the utility, which is based in Jackson, Michigan, has no such intentions. Consumers sold another would-be site near the lake years ago due to environmental and logistical issues, as well as potential prices in the billions. It is currently renovating the existing facility in collaboration with co-owner DTE Energy.

Building a new one “doesn’t make financial sense,” according to Gustad. “I don’t see that occurring anytime soon until we get some aid from the state or federal government.”

Remained in neutral

The company’s decision exemplifies the issues that pumped storage faces in the United States, where these systems account for roughly 93 percent of utility-scale energy in reserve. While economists predict that demand for power storage will skyrocket, the industry’s growth has been slow.

The country has 43 pumped storage facilities with a combined capacity of 22 gigatonnes, equivalent to the production of as many nuclear power plants. However, just one minor operation has been added since 1995, and it is unknown how many of the more than 90 planned operations will be able to overcome economic, regulatory, and logistical constraints that cause protracted delays.

The Federal Energy Regulatory Commission has granted licenses to three projects, but none is being built. Work on a long-planned Oregon plant is expected to begin in 2023, according to developers. Before construction can begin, a Montana firm that received a license five years ago requires a utility to operate the plant and purchase storage space.

In comparison, more than 60 are currently under construction around the world, most of them in Europe, India, China, and Japan.

“The permission process is insane,” Malcolm Woolf, head of the National Hydropower Association, said during a Senate Energy and Natural Resources Committee hearing in January, claiming that it includes too many authorities.

Although FERC approves new facilities and relicenses existing ones, other federal, state, and tribal agencies also have a role, according to Celeste Miller, a FERC spokesperson. Every project is distinct. Each has a unique set of problems, “she stated.

The industry is advocating for an investment tax credit similar to that received by solar and wind. The tax break is included in President Joe Biden’s “Build Back Better” initiative, which has now stalled in Congress.

Pumped storage first appeared in the early 1930s. However, most systems were created decades later to store excess electricity generated by nuclear power reactors and release it when needed.

The storage facilities also function as a safety net in the event of a power outage. When a New England nuclear unit went offline in 2020, “the lights in Boston didn’t flicker,” according to Woolf, because two pumped storage stations provided backup power.

While nuclear, coal, and natural gas facilities can run constantly, wind and solar cannot, so the demand for reserve power is expected to expand. According to National Renewable Energy Laboratory projections, storage capacity in the United States might increase more than fivefold by 2050.

“Over the next several years, we’ll bring hundreds of gigatonnes of renewable energy onto the grid, and we need to be able to use that energy wherever and whenever it’s needed,” Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm said last year.

LOCATION, LOCATION, LOCATION

Engineers at Australian National University used computer mapping to identify more than 600,000 “possibly feasible” pumped storage sites around the world, including 32,000 in the United States, that could store 100 times the energy required to power a global renewable electricity network.

However, the study did not consider whether the sites would meet environmental or cultural protection standards or whether they would be commercially feasible. According to its website, “many, if not most, may prove to be undesirable.”

Environmentalists are skeptical of pumped storage because reservoirs are often constructed by hydropower dams, which obstruct fish migration, degrade water quality, and generate methane, a powerful greenhouse gas. Furthermore, most plants constantly draw water from rivers.

Recent ideas, however, foresee “closed-loop” systems that tap a surface or subsurface source and then cycle that water between reservoirs frequently. Water would only be added to compensate for evaporation or leaks.

The Hydropower Reform Coalition, which represents conservation groups, says such projects might be supported under “extremely limited circumstances.”

However, others are encountering opposition, such as the Goldendale Energy Storage Project in Washington State. It would transport water between two reservoirs of 60 acres (24.3 hectares) each on opposing slopes of a hill.

According to Rye Development, which is pushing the project, the plant could power roughly 500,000 homes for up to 12 hours. It is applying for FERC licensing and is set to go online in 2028, but it still needs a state water quality permit.

Environmentalists are concerned about the project’s impact on wetlands and wildlife habitats, while tribes claim it will intrude on a sacred place.

What are we ready to give up to bring this technology online? “asked Bridget Moran, associate director of American Rivers.

According to the developers, the project would include cleaning up the contaminated lower reservoir area.

The United States Department of Energy has released a web-based tool to assist developers in locating the optimum places.

Recent Michigan Technological University research found hundreds of abandoned mines in the United States that could be used for pumped storage, with top reservoirs at or near the surface and lower reservoirs below the earth.

According to the research, they are close enough to transmission and distribution infrastructure, as well as solar and wind generation facilities.

“All these holes in the ground are ready to go,” said study co-leader and energy policy associate professor Roman Sidortsov.

While some decommissioned mines may be healthier for the environment, a project in New York’s Essex County has been halted due to worries about water pollution.

Future Competitiveness

New technologies are emerging as the market for stored energy expands.

Quidnet Energy, based in Texas, has created a pumped storage technology that drives water underground, traps it between rock layers, and then releases it to power turbines. In March, the business announced a collaboration with San Antonio’s municipal utility.

Energy Vault, a Swiss firm, developed a crane that uses renewable energy to lift and stack 35-ton bricks. When energy is required, wires drop the bricks, spinning a generator.

Batteries are currently the primary challenger to pumped storage systems, which can supply power for eight to sixteen hours. Longer-lasting lithium-ion batteries normally last four hours, but longer-lasting models are being developed.

Is it possible that an eight-hour battery will be less expensive than a pumped storage plant? That is the multibillion-dollar question, “said Paul Denholm, a National Renewable Energy Laboratory analyst.

According to a 2016 Energy Department analysis, the US network has the potential for 36 gigatonnes of new pumped storage capacity.

“We don’t believe pumped storage is the be-all and end-all of storage, but it is an important element of our storage future,” said Cameron Schilling, vice president of markets for the hydropower organization. “Without it, you can’t decarbonize the system.”