With assistance from an accomplished submerged cave-plunging group, Northwestern College scientists have developed the absolute most complete guide to date of the microbial networks living in the lowered mazes underneath Mexico’s Yucatán Landmass.

Albeit past scientists have gathered water and microbial examples from the cavern doorways and effectively open sinkholes, the Northwestern-drove group arrived at the most unfathomable ways of dim waters to see better what can make due inside this exceptional underground domain.

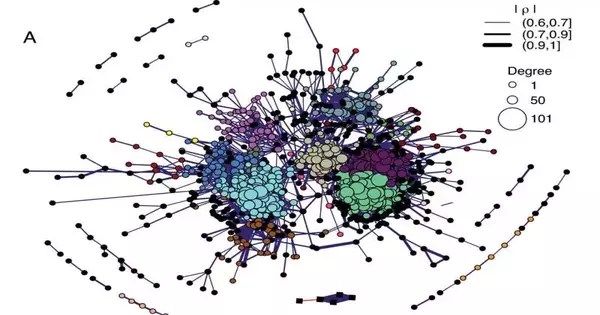

Subsequent to examining the examples, the scientists noticed a framework rich with variety, coordinated into particular examples. Like a cliché secondary school break room, microbial networks inside the cavern framework will more often than not group into distinct factions. In any case, one group of microorganisms (Comamonadaceae) went about as a famous extrovert, showing up at almost 66% of the “cafeteria tables.” The discoveries hint that Comamonadaceae is the key environmental part of the more extensive local area.

“The microbial communities divide into distinct niches. There are a variety of characters who appear to move around depending on where you look. However, when you look at the entire data set, there is a core set of organisms that appear to be playing key roles in each ecosystem.”

Osburn is an associate professor of Earth and planetary sciences at Northwestern’s Weinberg College of Arts and Sciences.

The examination was distributed in the journal Applied and Ecological Microbial Science.

“This is surely the most sweeping microbial overview across this area of the planet,” said Northwestern’s Magdalena R. Osburn, who drove the review. “These are amazingly unique examples of underground waterways that are especially hard to find. From those examples, we had the option of grouping the qualities based on the microbial populations that live in these destinations. This underground stream framework gives drinking water to a great many individuals. In this way, whatever occurs with the microbial networks there can possibly be felt by people.”

A geobiology master, Osburn is an academic administrator of Earth and planetary sciences at Northwestern’s Weinberg School of Expressions and Sciences.

Northwestern former student Matthew Selensky drove this task as a piece of his paper when he was an alumni understudy in Osburn’s research center. Concentrate on co-creator Patricia Beddows, teacher of Earth and planetary sciences at Weinberg, who drove the cavern plunging endeavor and utilized her time of involvement chipping away at these caverns. Other Northwestern co-creators include Andrew Jacobson, a teacher of Earth and planetary sciences, and previous alumni understudy Karyn DeFranco, who zeroed in on geochemistry.

Found basically in southeastern Mexico, the broad Yucatán carbonate spring is blemished by various sinkholes, prompting a perplexing trap of submerged caves. Facilitating a different yet understudied microbiome, the submerged organization contains areas of freshwater, seawater, and combinations of both. The framework likewise incorporates various zones—from completely dark, profound pits with no immediate openings to the surface to shallower sinkholes shining with daylight.

“The Yucatan stage is basically a Swiss cheese of cavern channels,” Osburn said. “We were interested in which organisms are found together when we look across the entire framework versus which microorganisms are tracked down inside one ‘neighborhood’.”

Concentrate on destinations. Bacterial and archaeal networks from 66 water tests traversing the brilliant, halocline, and saline groundwater layers in the spring were examined in duplicate and contrasted with Caribbean seawater. Networks were tested from 11 springs and 3 surface seawater destinations close to Tulum, Quintana Roo, Mexico. Destinations are colored by cave frameworks, as indicated by recently planned courses. The brilliant water ordinarily streams toward the coast, despite the fact that decoupled saline groundwater may, on the other hand, stream coastward and inland in view of ocean level (11). Allude to Table 1 in the fundamental text for site portrayals and mark IDs. Site Xel Ha (XeH) was examined in two course branches. The base guide was developed utilizing the R bundle ggmap (Kahle and Wickham, 2013). Credit: Applied and Ecological Microbial Science (2023). DOI: 10.1128/aem.01682-23

To investigate this inquiry, a group of cavern jumpers gathered 78 water tests from 12 individual locales inside the cavern framework close to the Caribbean coast in Quintana Roo, Mexico. The example assortment crossed from the Xunaan Ha framework at the north end to the inland and beachfront segments of the Sac Actun framework (counting an unmistakable, 60-meter-profound pit) to the Bull Bel Ha framework toward the south.

Back in a plunge shop-turned-science lab, specialists sifted cells through each example and dissected its science. Then, back at Northwestern, they recognized microbial networks by sequencing their DNA. Then, Selensky developed another computational program to perform network examinations on the informational index.

The subsequent organizations showed which species will more often than not live, respectively. For each site, the scientists considered the ecological setting of each microbial local area, including cave type (pit or channel), cave framework, distance from the Caribbean coast, geochemistry, and position in the water segment.

In spite of the fact that water from the Bay of Mexico streams into the Yucatán spring, the spring’s microbiome changes significantly from the nearby ocean, the scientists found. The microbiomes likewise fluctuate all through the cavern framework—from one cavern to another and from shallow water to profound water.

“The microbial networks structure particular specialties,” Osburn said. “There is a differing cast of characters that appear to move around, contingent upon where you look. Yet, when you look across the entire informational collection, there’s a central arrangement of organic entities that appear to be performing key jobs in every environment.”

Osburn and her group found that Comamonadaceae, a group of microscopic organisms normally found in groundwater frameworks, lived in a few specialties. They additionally found that a profound, pit-like sinkhole with a surface opening (permitting daylight to spill in) housed the most microbial networks—isolated into layers of unmistakable specialties all through the water segment.

“It appears to be that Comamonadaceae performs somewhat various jobs in various pieces of the spring; however, it’s continuously playing out a significant job,” Osburn said. “Contingent upon the locale, it has an alternate accomplice. Comamonadaceae and their accomplices likely have some mutualistic digestion, perhaps sharing food.”

More information: Magdalena R. Osburn et al., Microbial biogeography of the eastern Yucatán carbonate aquifer, Applied and Environmental Microbiology (2023). DOI: 10.1128/aem.01682-23