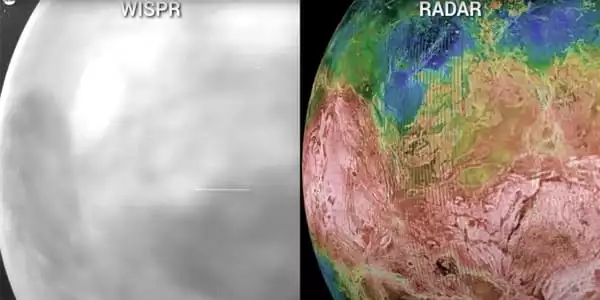

NASA has revealed that the Parker Solar Probe has captured the first visible-light photographs of Venus’s surface from space. The probe, which was built to study the sun, has used Venus in gravity assist operations, providing a close-up glimpse of the steamy, cloud-enshrouded planet. When Parker sailed by Venus’s nightside in 2020, its Wide-Field Imager (WISPR) camera captured photographs of the planet that showed its surface characteristics.

How might a satellite camera see through Venus’s dense atmosphere? The surface of Venus is so heated that it shines in the longest wavelengths of light, close to infrared. This radiance was captured by the camera in the darkness of the planet’s nightside. By serendipity, scientists have photographed Venus’ surface from space for the first time.

Despite the planet’s rocky body being hidden beneath a thick veil of clouds, telescopes aboard NASA’s Parker Solar Probe were able to obtain the first visible-light photographs of the surface taken from orbit, according to researchers who published their findings in Geophysical Research Letters.

We’ve never seen the surface through the clouds at these wavelengths before. The gravitational pull of the planet pulls on the probe, narrowing its orbit and bringing it closer to the sun. The spacecraft made headlines when it became the first probe to penetrate the sun’s atmosphere thanks to Venus’s assistance.

Lori Glaze

“We’ve never seen the surface through the clouds at these wavelengths before,” stated Lori Glaze, Director of NASA’s Planetary Science Division, during a live Twitter broadcast. Despite the fact that the Parker Solar Probe was designed to study the sun, it must undertake repeated flybys of Venus. The gravitational pull of the planet pulls on the probe, narrowing its orbit and bringing it closer to the sun. The spacecraft made headlines when it became the first probe to penetrate the sun’s atmosphere thanks to Venus’s assistance.

It was during two such flybys in July 2020 and February 2021 that the probe’s WISPR telescopes captured the new images. While WISPR found Venus’ dayside too bright to image, it was able to discern large-scale surface features, such as the vast highland region called Aphrodite Terra, through the clouds on the nightside.

Light is scattered and absorbed by clouds. However, depending on the chemical makeup of the clouds, some wavelengths of light pass through, according to Paul Byrne, a planetary scientist at Washington University in St. Louis who was not involved in the study.

Though scientists were aware that such spectrum windows exist in Venus’ dense clouds of sulfuric acid, they did not expect light visible to human eyes to break through so strongly. WISPR was built to investigate the sun’s atmosphere, but its design also allows it to detect this unexpected window of light in Venus’ clouds. “It was fortunate that they had a device that could see through the clouds,” Byrne recalls.

Venus exudes mystery because its clouds are so dense that they obscure the planet. To make matters worse, its temperature is so high that it is inhospitable to spaceships. To date, the Russian Venera space probes are the only spacecraft to have ever landed on the surface of Venus, and their lives were brief. They survived from 23 minutes to two hours, transmitting back photos of the rocks and dirt in their landing location before succumbing to the planet’s extreme temperatures and pressures.

The photographs show a planet so hot that it glows, much like red-hot iron, said Brian Wood, an astrophysicist at the U.S. Naval Research Laboratory in Washington, D.C., and a coauthor of the paper, during the social media event.

“The pattern of light and dark that you see is basically a temperature map,” he explained, implying that brighter areas are hotter and darker areas are cooler. This pattern corresponds well with prior topographic maps produced by radar and infrared studies. According to Wood, the highlands appear dark while the lowlands appear bright.

The photographs are being released as NASA prepares to send two missions to Venus. The fresh images, according to Wood, “may aid in the interpretation of future observations from these new missions.”

The WISPR camera on Parker recorded wavelengths ranging from 470 to 800 nanometers. Light has a visible wavelength range of 380 to 750 nanometers. WISPR photos were utilized by scientists to create a film of Venus’s nightside. Airglow can be seen in the atmosphere, and there are dark and light surface characteristics beneath.