Competition between plants and animals for food, mates and living spaces is a major factor in evolution when there are little resources available. Given that there are numerous species of closely related rhododendrons that coexist peacefully, it follows that the flower-covered meadows of China’s Hengduan highlands were an evolutionary enigma.

The reason the plants were able to coexist was that they bloom at different times of the season so they don’t have to compete for pollinators, as was revealed by scientists who spent a whole summer carefully monitoring the flowering patterns of 34 Rhododendron species.

“There’s this basic idea in the ecology of the niche, that a species’s lifestyle, like what it eats and how it fits into the environment, cannot be replicated in the same community. If two species with the same lifestyle are living in the same space, they’ll compete with each other, so either one or both of them will adapt to have different, non-overlapping lifestyles, or they’ll go extinct,” says Rick Ree, a curator at the Field Museum in Chicago and senior author of the new study in the Journal of Ecology. “Since there are so many closely-related species of rhododendrons all living together in these mountains, we wanted to figure out how they were able to co-exist.”

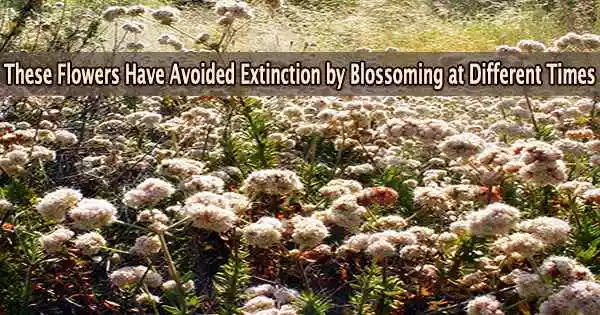

Rhododendrons are flowering shrubs; you’ve probably seen some species (like azaleas) for sale at the garden center. The Hengduan Mountains, which are close to the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau, are what biologists refer to as a “biodiversity hotspot”: an area that is environmentally vulnerable and has extremely high diversity.

“They form thickets along the sides of the mountains, it looks like an ocean of flowers,” says Qin Li, a postdoctoral researcher at the Field Museum and the paper’s lead author.

“The Rhododendron diversity in this area is caused in part by speciation, which is when new species diverge from a common ancestor,” says Ree. “Newly diverged species are expected to be much more ecologically similar, with the same sort of lifestyles, than species that are more distantly related.”

That makes it much more likely that the closely related rhododendrons in the Hengduan Mountains will compete with one another for resources. There are many ways that plants might adapt to coexist when they are in competition with one another.

The question is, how are plant communities around the globe going to respond? Weather is part of what signals them to blossom, and since climate change affects the weather, it’s likely to shift that competitive landscape. When the environment changes, species have three choices: you move, you adapt, or you die. Climate change is accelerating that dynamic.

Rick Ree

“They can become very different in terms of their preferences for soil, light, and moisture, very basic physiological functional traits. They can also evolve differences to reduce this potential for cross-pollination or competing for pollinators. That would be manifested through differences in flower shape, size, or color, or could be manifested in when they make their flowers available for pollinators,” says Ree. “By partitioning that timeline, they can reduce their chances of wasting their pollen and the resources that go into reproduction.”

To explain why the rhododendrons hadn’t wiped each other out, all of these evolutionary theories were on the table. Li led a two-month fieldwork excursion to China’s Mount Gongga to conduct a thorough examination of the area after selecting it for her study after a four-month trip on rhododendron the previous year throughout the more expansive Hengduan Mountains.

“I’d never done fieldwork in southwestern China before, but we were actually pretty close to my hometown in Sichuan province,” says Li. “With my field assistant and co-author Ji Wang from Sichuan University, I spent more than two months going to more than 100 sites, and we visited each of these sites four times throughout the season.”

Following months of recording the ecological traits of the plants, such as the size and form of the leaves and flowers as well as the times when the plants were in bloom, Li and her colleagues evaluated the data and used statistical methods to look for trends. They came to the conclusion that the plants’ ability to flower at various times was the key to their ability to coexist.

“Going in, we had a hunch that timing would be important, but we weren’t super certain,” says Ree. “It’s kind of conspicuous that there’s a long season where you can see flowers in the Himalaya region there are some species that put out striking blossoms against a backdrop of a field of snow, and others that wait till the end of the summer. Our analysis of the data confirms that suspicion.”

The results of the study shed light on one of numerous strategies used by plants to diversity without annihilating one another. But because timing is crucial for the diversity of rhododendrons on Mount Gongga, the climatic issue offers an additional hazard to these plants.

“There’s abundant evidence that the pace of climate change is messing with plants’ flowering times, causing population declines and extinctions,” says Ree.

“The question is, how are plant communities around the globe going to respond? Weather is part of what signals them to blossom, and since climate change affects the weather, it’s likely to shift that competitive landscape. When the environment changes, species have three choices: you move, you adapt, or you die. Climate change is accelerating that dynamic.”