A ferocious pack of predatory dinosaurs may have spent much of their time hunting in the water. Researchers write in Nature that an examination of the bone density of certain sharp-toothed spinosaurs reveals that several members of this dino group were primarily aquatic.

This discovery is the latest salvo in a continuing challenge to the widely held belief that all dinosaurs were land-based creatures, leaving the worlds of water and air to marine reptiles like Mosasaurus and flying reptiles like Pteranodon. However, other experts argue that the discovery does not indicate that Spinosaurus and its relatives swam.

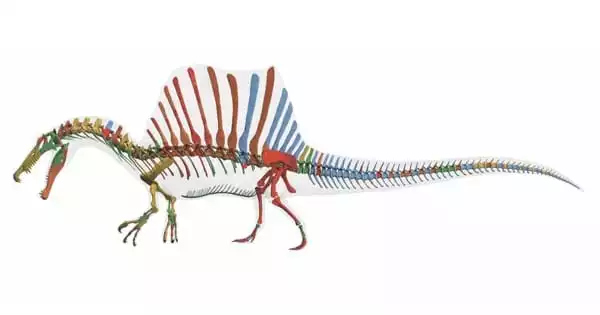

Nizar Ibrahim, a vertebrate paleontologist presently at the University of Portsmouth in England, and colleagues stitched together a 15-meter-long Spinosaurus specimen from what is now Morocco in 2014. The dinosaur’s unusual traits — a big sail-like structure on its back, small and powerful legs, nostrils set well back from its snout, and needlelike teeth that appeared to be specialized for hooking fish — suggested to the researchers that the predator was a swimmer. It has exceptionally solid leg bones, which is a trait of some aquatic organisms, such as manatees, who rely on the bones for ballast to stay underwater.

Ibrahim and his colleagues returned to the subject of bone density in the new study to see if it’s a reliable predictor of how much time a species spends in the water. According to Ibrahim, the researchers compiled “a large dataset” of femur and dorsal rib bone densities from “an unbelievable menagerie of extinct and extant creatures, reaching out to museum curators all across the world.”

This discovery is the latest salvo in a continuing challenge to the widely held belief that all dinosaurs were land-based creatures, leaving the worlds of water and air to marine reptiles like Mosasaurus and flying reptiles like Pteranodon.

Nizar Ibrahim

Spinosaurs such as the flamboyant, sail-backed Spinosaurus, as well as its equally sharp-toothed cousins Baryonyx and Suchomimus, are among the members of this assemblage. Other groups of dinosaurs, extinct marine reptiles, pterosaurs, birds, current crocodiles, and marine mammals are also included.

The scientists then matched these bone analyses to the various species in the study’s water-dwelling behaviors. According to the team’s findings, density is a “great signal” for species in the early phases of transitioning from land to water. Those tiny bones can allow transitional organisms, which may lack traits like fins or flippers to help them maneuver in the water more efficiently, seek underwater — a process the team refers to as “subaqueous foraging.”

The results further suggest that not only Spinosaurus, but also Baryonyx, had extraordinarily dense bones. According to the researchers, this shows that both of these dinosaurs were subaqueous foragers. That idea builds on previous work by Ibrahim and colleagues that proposed that Spinosaurus didn’t just spend much of its time in the water, but could actually swim in pursuit of prey, thanks to its odd, paddle-shaped tail.

The concept of a swimming Spinosaurus has not been universally accepted. A research published in Palaeontologia Electronica in 2021 examined Spinosaurus’ anatomy in depth and arrived to a different result. According to David Hone, a zoologist and paleobiologist at Queen Mary University of London, and Thomas Holtz Jr., a vertebrate paleontologist at the University of Maryland in College Park, the dinosaur was not a highly specialized aquatic predator. Spinosaurus may have just waded in the shallows, heron-like, to fish.

Those who are skeptical have not been persuaded by the latest findings. Spinosaurus possesses “obviously very thick bones.” “This is extremely good proof that they’re hanging around in water,” Hone says. “What they’re doing in the water is unclear.” That is the point of contention.”

Consider hippos, who spend the majority of their time submerged, according to Hone. “Hippos have bone densities that are completely comparable to Spinosaurus and Baryonyx, but they don’t eat in the water,” he adds, and they don’t swim.

“Everyone has been in agreement that Spinosaurus was more aquatic than other big theropods” like Tyrannosaurus rex, Holtz says. That Baryonyx also had dense bones was a bit of an interesting surprise, he adds.

But dense bones or not, Holtz says, “it still doesn’t turn them into aquatic hunters.” He describes several anatomical features — Spinosaurus’ long slender neck, tilted head and arrangement of neck muscles that suggest a downward striking motion — that point more to a wading creature that hunted from above the water surface than one that chased its prey underwater.

Kiersten Formoso, a vertebrate paleobiologist at the University of Southern California in Los Angeles, says the new comparison of bone densities among a wide variety of creatures is a valuable addition that she plans to use in her own research on the transition of ancient creatures from land to water. But she isn’t sure that it implies Spinosaurus and Baryonyx could swim.

“I would never take Spinosaurus out of the water,” Formoso says. But, she says, more research on its biomechanics — how it would have moved — is needed to determine how adeptly aquatic the dinosaur might have been.