It is no distortion to say the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) addresses another time in current cosmology.

Sent off on December 25 of last year and completely functional since July, the telescope offers looks at the universe that were previously distant to us. Like the Hubble Space Telescope, the JWST is in space, so it can take pictures with dazzling subtlety liberated from the bends of Earth’s air.

In any case, while Hubble is in a circle around Earth at a height of 540 kilometers, the JWST is 1.5 million kilometers away, a long way past the moon. From this position, away from the impedance of our planet’s reflected intensity, it can gather light from across the universe, far into the infrared part of the electromagnetic range.

This capacity, when combined with the JWST’s bigger mirror, cutting-edge finders, and numerous other mechanical advances, permits stargazers to think back to the universe’s earliest ages.

As the universe grows, it extends the frequency of light going towards us, making more far-off objects seem redder. At incredible enough distances, the light from a world is moved completely out of the noticeable part of the electromagnetic range and into the infrared. The JWST can test such light sources all the way back to almost the beginning of time.

The Hubble telescope keeps on being an incredible logical instrument and can see at optical frequencies where the JWST can’t. Yet, the Webb telescope can see a lot further into the infrared with more prominent responsiveness and sharpness.

We should view ten pictures that have shown the amazing force of this new window to the universe.

1. Reflect arrangement is complete.

Left: The main openly delivered arrangement picture from the JWST. Stargazers hopped on this picture to contrast it with past pictures of a similar piece of sky like that on the right from the Dim Energy Camera on the planet.

In spite of long periods of testing on the ground, an observatory as perplexing as the JWST required broad setup and testing once exposed to the dim light of space.

One of the greatest errands was getting the 18 hexagonal mirror portions unfurled and adjusted to a small part of the frequency of light. In spring, NASA delivered the main picture (fixed on a star) from the completely adjusted reflect. Despite the fact that it was only an alignment picture, stargazers quickly contrasted it with existing pictures of that patch of sky—with extensive fervor.

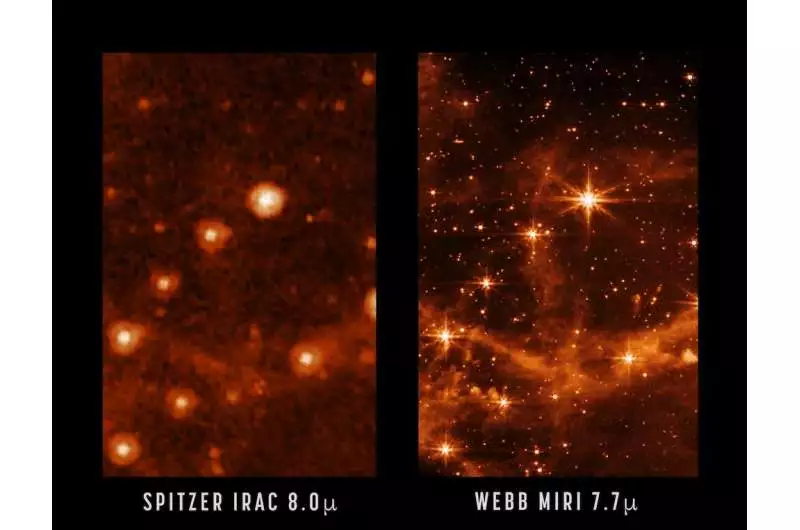

2. Spitzer versus MIRI

This image shows a portion of the “Mainstays of Creation” in infrared (see below); Spitzer Space Telescope on the left, and JWST on the right. The distinction between top to bottom and goal is an emotional one.

This early image, taken while all of the cameras were centered, clearly shows the step change in information quality that JWST brings over its forefathers.

On the left is a picture from the Spitzer telescope, a space-based infrared observatory with an 85-cm mirror; on the right, a similar field from JWST’s mid-infrared MIRI camera and 6.5-m mirror. The goal and capacity to identify much fainter sources are on display here, with many things apparent that were lost in the clamor of the Spitzer picture. This is what a larger mirror arranged in the deepest, coldest dim can do.

3. The main world group image

SMACS 0723 world group, from Hubble on the left and JWST on the right. Hundreds of additional worlds are apparent in JWST’s infrared picture.

The world bunch with the dull name of SMACS J0723.3-7327 was a decent decision for the main variety of pictures delivered to general society from the JWST.

The field is packed with worlds of all shapes and tones. The joined mass of this huge world bunch, located about 4 billion light years away, twists space so that light from far-off sources behind the scenes is extended and amplified, an impact known as gravitational lensing.

These twisted foundation worlds can be plainly viewed as lines and curves all through this picture. The field is now fabulous in Hubble pictures (left), yet the JWST close infrared picture (right) uncovers an abundance of additional detail, including many far-off worlds that are excessively weak or too red to ever be recognized by their ancestor.

4. Stephan’s Quintet

Hubble (l) and JWST (r) images of “Stephan’s Quintet,” a grouping of worlds. The inset shows a focus on a far-off foundation world.

These pictures portray a fabulous gathering of worlds known as Stephan’s Quintet, a gathering that has for some time been important to stargazers concentrating on the way impacting systems connect with each other gravitationally.

On the left, we see the Hubble view, and on the right, the JWST mid-infrared view. The inset shows the force of the new telescope, with a focus on a little foundation world. In the Hubble picture, we see some splendid star-shaping areas, yet only with the JWST does the full design of these and surrounding worlds reveal itself.

5. The Mainstays of Creation

The “Mainstays of Creation,” a star-framing locale of our world, as caught by Hubble (left) and JWST (right).

The supposed Mainstays of Creation, taken by Hubble in 1995, is possibly the most popular image in all of cosmology.It showed the uncommon reach of a space-based telescope.

It portrays a star-shaping locale in the Hawk Cloud, where interstellar gas and residue give the setting to a heavenly nursery overflowing with new stars. The picture on the right, taken with the JWST’s close-infrared camera (NIRCam), shows a further benefit of infrared cosmology: the capacity to look through the cover of residue and see what exists in and behind.

6. The “hourglass” protostar

The “hourglass protostar,” a star that remains stationary while accumulating enough gases to begin fusing hydrogen. Inset: A much lower goal view from Spitzer.

This image portrays another episode of galaxy creation within the Milky Way. This hourglass-shaped structure is a cloud of dust and gas surrounding a protostar named L1527 in the process of creation.

Just noticeable in the infrared, a “growth plate” of material falling in (the dark band in the middle) will ultimately empower the protostar to assemble sufficient mass to begin melding hydrogen, and another star will be conceived.

Meanwhile, light from the yet-to-be-framed star illuminates the gas above and beneath the plate, giving it the hourglass shape.Again, Spitzer provided our previous perspective on this; how much detail is a huge leap ahead.

7. Jupiter in infrared

An infrared perspective on Jupiter from the JWST Note the auroral shine at the posts; this is brought about by the connection of charged particles from the sun with Jupiter’s attractive field.

The primary goal of the Webb telescope is to image the most distant worlds from the beginning of time, but it can also look somewhat closer to home.

Despite the fact that JWST can’t take a gander at Earth or the inward Planetary Group planets—aas it should constantly face away from the Sun—iit can search externally at the more far-off pieces of our Planetary Group. This close-up infrared picture of Jupiter is a lovely model, as we look profoundly into the design of the gas giant’s mists and tempests. The shine of auroras at both the northern and southern poles is tormenting.

This picture was very hard to accomplish because of the quick movement of Jupiter across the sky in comparison with the stars and due to its quick turn. The achievement demonstrated the Webb telescope’s capacity to follow troublesome cosmic targets very well.

8. The Ghost World

Hubble’s apparent light (l), JWST’s infrared (r), and joined (center) pictures of the “Ghost World” M74 The capacity to join apparent light data about stars with infrared pictures of gas and residue permits us to test such worlds in lovely detail.

These images of the alleged Ghost World, or M74, reveal the JWST’s power not only as the best in class of cosmic instruments, but also as an important supplement to other extraordinary devices. The center board here joins apparent light from Hubble with infrared from Webb, permitting us to perceive how starlight (through Hubble) and gas and residue (by means of JWST) together shape this amazing world.

Much JWST science is intended to be joined with Hubble’s optical perspectives and other imaging to use this rule.

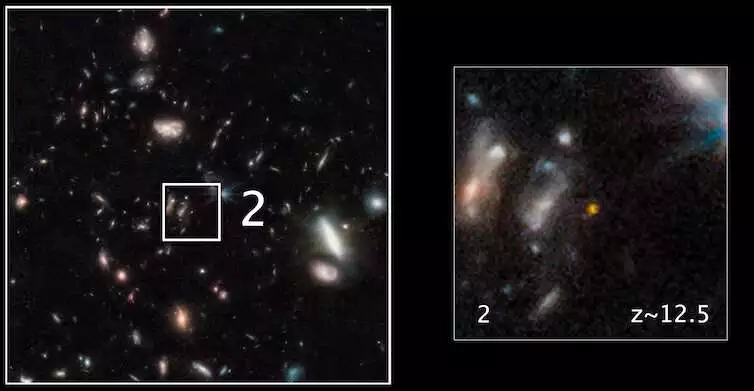

9. A super-far-off world

A “focus in” on a world from one of the universe’s early ages, around 300 million years ago (the little red source visible in the focal point of the right board).In visible light, worlds at this distance are difficult to identify because their produced radiation has been “redshifted” far into the infrared.

Although this world—the small, red mass in the right image—isn’t among the most fantastically pleasant that our universe has to offer, it is equally fascinating logically.

This preview is from when the universe was a simple 350 million years old, making this among the very first worlds to have been shaped. Understanding the nuances of how such worlds develop and converge to form systems like our own 13 billion years later is a critical inquiry, and one with many excess secrets, making revelations like this profoundly pursued.

It is likewise a view that only the JWST can accomplish. Stargazers didn’t know very well what was in store; a picture of this world taken with Hubble would seem clear, as the radiance of the system is extended far into the infrared by the extension of the universe.

10. This goliath mosaic of Abell 2744

A picture of the world group Abell 2744 made by joining various JWST openings In this small piece of the sky (a negligible part of a full moon), pretty much all of the many items shown are from a far-off world.

This picture (click here for full view) is a mosaic (numerous singular pictures sewn together) focused on the goliath Abell 2744 world bunch, casually known as “Pandora’s Group.” The sheer number and assortment of sources that the JWST can identify is stunning; except for a small bunch of prominent stars, each spot of light addresses a whole system.

In a dim sky no bigger than a small part of the full moon, there are umpteen great worlds, truly bringing back the sheer size of the universe we occupy. Expert and novice astronomers alike can spend hours poring over this image for anomalies and secrets.

Throughout the next few years, JWST’s capacity to look so profoundly and far back into the universe will permit us to address many inquiries regarding how we became. Similarly energizing are the revelations and questions we cannot as yet predict. These obscure questions are bound to arise when you peel back the cloak of time as only this new telescope can.

Provided by The Conversation