Scientists have discovered that long-term calorie restriction provides a plethora of benefits in animals over the last few decades. Researchers have assumed that reduced food intake was responsible for these benefits by reprogramming metabolism. However, a new study finds that reducing calorie intake alone is insufficient; fasting is required for mice to reap the full benefits.

Researchers have assumed that reduced food intake was responsible for these benefits by reprogramming metabolism. However, a new study from the University of Wisconsin-Madison researchers finds that calorie restriction alone is insufficient; fasting is required for mice to reap the full benefit.

The new findings add to preliminary evidence that fasting can improve people’s health, as trends like intermittent fasting continue to gain traction. These human and animal studies have added to the growing picture of how when and what we eat, rather than just how much, affects our health. The study emphasizes the complexities of nutrition and metabolism while also providing guidance to researchers attempting to decipher the true causes of diet-induced health benefits in animals and humans.

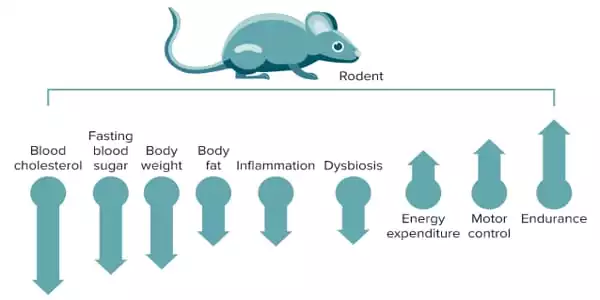

Over the last few decades, we have discovered that long-term calorie restriction provides a wealth of benefits in animals: lower weight, better blood sugar control, even longer lifespans.

Dudley Lamming

Fasting, when combined with eating less, reduces frailty in old age and increases the lifespan of mice, according to the researchers. Fasting can also improve blood sugar and liver metabolism on its own. Surprisingly, mice who ate fewer calories but never fasted died younger than mice who ate whatever they wanted, implying that calorie restriction alone may be harmful.

Dudley Lamming of the UW School of Medicine and Public Health, his graduate student Heidi Pak, and colleagues from UW-Madison and other institutions led the study. The team’s findings were published in the journal Nature Metabolism.

Pak and Lamming were inspired to conduct the study after discovering that previous studies had unintentionally combined calorie restrictions with long fasts by feeding animals only once a day. It was difficult to separate the effects of one from the effects of the other.

“Everyone saw this overlap of treatment – both reducing calories and imposing a fast – but it wasn’t always obvious that it had biological significance,” says Lamming, who has long studied the effect of restricted diets ocouldn metabolism. “It was only in the last few years that people became interested in this issue.”

Lamming’s team devised four different diets for mice to follow in order to untangle these factors. One group was allowed to eat as much as they wanted whenever they wanted. Another group ate the full amount but in a short period of time, resulting in a long daily fast without calorie reduction.

The other two groups were given approximately 30% fewer calories, either once a day or spread out over the course of the day. This meant that some mice had a long daily fast, while others ate the same reduced-calorie diet but never fasted, which differed from most previous calorie restriction studies.

Many of the benefits originally attributed to calorie restriction alone — better blood sugar control, healthier use of fat for energy, protection from frailty in old age, and longer lifespans — turned out to require fasting as well. Mice that ate fewer calories without fasting did not experience these benefits.

Fasting without calorie restriction was just as effective as calorie restriction combined with fasting. Fasting alone was sufficient to improve insulin sensitivity and reprogram metabolism to prioritize fats as a source of energy. Fasting mice’s livers also exhibited signs of improved metabolism.

The researchers did not investigate the effect of fasting alone on longevity or frailty in mice as they aged, but previous research has suggested that fasting can provide these benefits as well. While mice that ate fewer calories without ever fasting had better blood sugar control, they died younger. When compared to mice that ate less and fasted, these mice that only ate less died about 8 months sooner on average.

“That was quite surprising,” says Lamming, despite the fact that other studies have shown some negative effects from calorie restriction. The team also assessed frailty using metrics such as grip strength and coat condition. “Aside from having shorter lifespans, these mice were worse in some aspects of frailty but better in others. So, while their frailty did not change significantly, they did not appear as healthy.”

The primary studies were conducted in male mice, but Lamming’s lab discovered that fasting had similar metabolic effects in female mice. The study demonstrates how difficult diet studies can be, even in a laboratory setting. This difficulty is exacerbated in human studies, which simply cannot match the level of control available in animal models. The new study can help guide future research into whether fasting improves human health.

“We need to know if fasting is necessary for people to see benefits,” Lamming says. “If fasting is the primary determinant of health, we should be researching drugs or diet interventions that mimic fasting rather than those that mimic fewer calories.”