Black holes, among of the most fascinating things in the universe, with such a tremendous gravitational attraction that not even light can escape. The discovery of gravitational waves in 2015, created by the merger of two black holes, offered a new window into the universe. Since then, scores of such observations have fueled astrophysicists’ search to comprehend their cosmic origins.

Using the POSYDON code’s recent major advances in simulating binary-star populations, a team of scientists from the University of Geneva (UNIGE), Northwestern University, and the University of Florida (UF) predicted the existence of merging massive, 30 solar mass black hole binaries in Milky Way-like galaxies, challenging previous theories. These findings were published in the journal Nature Astronomy.

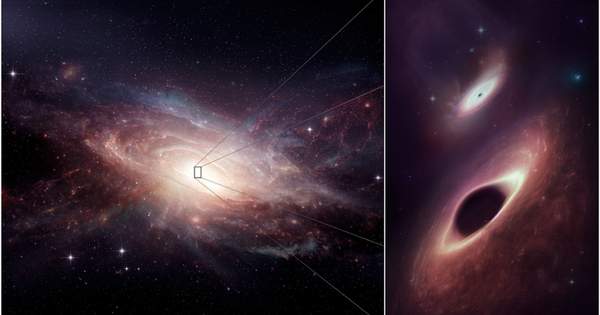

Stellar-mass black holes are astronomical objects formed by the collapse of stars with masses ranging from a few hundred to thousands of times that of our sun. Because their gravitational field is so strong, neither matter nor radiation can escape, making detection extremely challenging. As a result, when the Laser Interferometer Gravitational-wave Observatory (LIGO) observed minuscule ripples in spacetime caused by the merger of two black holes in 2015, it was heralded as a watershed event. The two merging black holes at the source of the signal, according to astrophysicists, were around 30 times the mass of the sun and 1.5 billion light-years apart.

As it is impossible to directly observe the formation of merging binary black holes, it is necessary to rely on simulations that reproduce their observational properties. We do this by simulating the binary-star systems from their birth to the formation of the binary black hole systems.

Simone Bavera

Bridging Theory and Observation

What mechanisms are responsible for the formation of these black holes? Are they the result of the evolution of two stars, comparable to our sun but much more massive, in a binary system? Or are they the consequence of black holes in densely populated star clusters colliding by chance? Or may a more bizarre mechanism be at work? All of these issues are still being argued today.

The POSYDON partnership, which includes scientists from the University of Geneva (UNIGE), Northwestern University, and the University of Florida (UF), has made substantial progress in modeling binary-star populations. This research is assisting in providing more precise answers and reconciling theoretical predictions with empirical facts.

“As it is impossible to directly observe the formation of merging binary black holes, it is necessary to rely on simulations that reproduce their observational properties. We do this by simulating the binary-star systems from their birth to the formation of the binary black hole systems,” explains Simone Bavera, a post-doctoral researcher at the Department of Astronomy of the UNIGE’s Faculty of Science and leading author of this study.

Pushing the Limits of Simulation

Interpreting the origins of merging binary black holes, such as those observed in 2015, requires comparing theoretical model predictions with actual observations. The technique used to model these systems is known as “binary population synthesis.”

“In order to estimate the statistical properties of the resulting gravitational-wave source population, this technique simulates the evolution of tens of millions of binary star systems.” To do so in a realistic time frame, researchers have hitherto relied on models that use approximation approaches to predict the evolution of stars and their binary interactions. As a result, oversimplification of single and binary stellar physics leads to less accurate predictions,” argues Anastasios Fragkos, assistant professor at the UNIGE Faculty of Science’s Department of Astronomy.

POSYDON has overcome these constraints. It is an open-source program that uses a wide library of pre-computed comprehensive single- and binary-star simulations to predict the evolution of isolated binary systems. Each of these complex simulations could take up to 100 CPU hours to complete on a supercomputer, limiting the applicability of this simulation technique to binary population synthesis.

“However, by pre-compiling a library of simulations that cover the entire parameter space of initial conditions, POSYDON can use this massive dataset in conjunction with machine learning methods to predict the entire evolution of binary systems in less than a second.” “This speed is comparable to previous-generation rapid population synthesis codes, but with improved accuracy,” says Jeffrey Andrews, assistant professor of physics at UF.

Introducing a New Model

“Prior to POSYDON, models predicted a negligible formation rate of merging binary black holes in Milky Way-like galaxies, and they did not predict the existence of merging black holes as massive as 30 times the mass of our sun.” “POSYDON has demonstrated that such massive black holes could exist in Milky Way-like galaxies,” says Vicky Kalogera, a Daniel I. Linzer Distinguished University Professor of Physics and Astronomy at Northwestern, director of the Centre of Interdisciplinary Exploration and Research in Astrophysics (CIERA), and co-author of this study.

Previous models overestimated certain aspects, such as the expansion of massive stars, which impacts their mass loss and the binary interactions. These elements are key ingredients that determine the properties of merging black holes. Thanks to fully self-consistent detailed stellar structure and binary-interaction simulations, POSYDON achieves more accurate predictions of merging binary black hole properties such as their masses and spins.

This is the first study to investigate merging binary black holes using the newly available open-source POSYDON software. It sheds new light on the mechanics of merging black holes in galaxies like our own. The research team is presently working on a new version of POSYDON that will feature a larger library of detailed star and binary simulations that will be capable of simulating binaries in a broader range of galaxy types.