It’s old, it’s huge, and it is wavering. The huge aspen stand named “Pando,” situated in south-central Utah, is in excess of 100 sections of land of trembling, hereditarily indistinguishable vegetation, remembered to be the biggest living creature on the planet (in view of dry weight mass, 13 million pounds). What resembles a shining scene of individual trees is really a gathering of hereditarily indistinguishable stems with a huge common root foundation.

Presently, after a lifetime that might have extended across centuries, the’shaking monster’ is starting to separate, as per new exploration.

The main thorough assessment of Pando was finished a long time back by Paul Rogers, assistant lecturer of biology in the Quinney School of Normal Assets and head of the Western Aspen Union. It showed that perusing deer (and less significantly, cows) were hurting the stand, restricting the development of new aspen suckers and putting a viable lapse date on the epic plant. As more seasoned trees matured out, new aspen sprouts weren’t enduring ravenous programs to supplant them. Pando was gradually passing on.

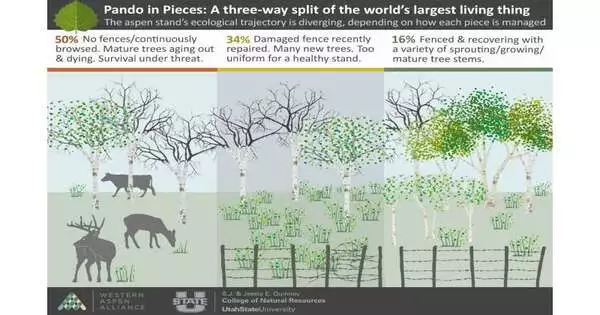

Because of the danger, chiefs raised fencing around a part of the stand to continue brushing creatures out, making a trial of sorts. Rogers has as of late gotten back to assess the system, and to do so well-mind the general strength of Pando. He detailed his discoveries in the journal Protection Science and Practice.

“I believe that if we try to save the organism solely through fences, we would end up creating something akin to a zoo in the wild. While the fencing technique is well-intended, we will eventually need to address the underlying issues of too many browsing deer and cattle on this landscape.”

Paul Rogers, adjunct professor of ecology in the Quinney College of Natural Resources

Pando is, by all accounts, following three unique natural ways in view of how the portions are made due, as per the exploration. Around 16% of the stand is enough to keep out perusing creatures; new aspen suckers enduring those first delicate years to lay out into new trees. Yet, across in excess of 33% of the stand, fencing had fallen into decay and was just being built up. In this area, past perusing has a negative impact; the old passing on trees dwarf the young.

Rebekah Adams and Etta Crowley take vegetation estimation under Pando, the world’s biggest living creature. A new assessment of the huge aspen stand in south-central Utah views that Pando appears to be in the following three unique natural ways in light of how the various portions are made due. Credit: Paul Rogers.

Also, the regions that stay unfenced (around half of the stand) keep on having concentrated degrees of deer and cows consuming the heft of youthful fledglings. These hard-hit zones are presently moving naturally in particular ways, said Rogers. Mature aspen stems pass on without being supplanted, opening the overstory and permitting more daylight to reliably arrive at the wood floor, which adjusts plant piece. These unfenced regions are encountering the fastest aspen decline, while the other fenced regions are taking their own novel courses—basically, separating these special, generally uniform, woods.

According to Rogers, the solution to Pando’s endurance is unlikely to be simply more wall.While unfenced regions are quickly vanishing, closing alone is empowering single-matured recovery in a wood that has supported itself throughout the long term by changing development. While this may not appear to be basic, aspen and understory development designs in conflict from the past are now happening, said Rogers.

In Utah and across the West, Pando is famous and something of a canary in the coal mineshaft. As a cornerstone animal type, aspen woods support elevated degrees of biodiversity — from chickadees to thimbleberry. As aspen environments thrive or lessen, subordinate species take action accordingly. Long-term disappointment for new enrollment in aspen frameworks may have ramifications for many species.

Moreover, there are stylish and philosophical issues with a fencing system, said Rogers.

“That’s what I feel, assuming we attempt to save the creature with walls alone, we’ll end up attempting to make something like a zoo in the wild,” said Rogers. “Although the fencing system is benevolent, we’ll at last have to resolve the basic issues of too many perusing deer and cows on this scene.”

Pando is an oddity. It is rumored to be the world’s biggest creature, yet it is nearly invisible in the 10,000 foot view of protection challenges across the globe — or even in Utah, he said. Yet, as an image, it addresses the destiny of the aspen variety and solid human connections with the earth at-large. Examples learned while safeguarding Pando likewise offer a viewpoint on the striving aspen woods crossing the world’s northern half of the globe.

More information: Paul C. Rogers, Pando’s pulse: Vital signs signal need for course correction at world‐renowned aspen forest, Conservation Science and Practice (2022). DOI: 10.1111/csp2.12804